Part One

Military madness was killing my country. Solitary sadness comes over me. – Graham Nash

Imagination is not a solitary thing. Unlike fantasy, which is self-centered, imagination implies dialogue – between what is and what could be. Consider that some languages lack the verb “to be.” Speakers grow up expecting to communicate indirectly, use metaphors freely and tolerate ambiguity. Metaphors serve as organizing frameworks that shape our thoughts about social reality. They are the language of poetry; they can leap the chasm between thoughts and transmit multiple levels of meaning.

As Joseph Campbell taught, the life of mythology springs from the metaphoric vigor of its symbols, which bring together and reconcile two contraries. When we think mythologically, we perceive meaning on several levels simultaneously, aware that the literal, psychological and symbolic dimensions of reality complement each other to make something greater than the sum of the parts.

But unimaginative language, said James Hillman, “displaces the metaphorical drive from its appropriate display in poetry and rhetoric…into direct action. The body becomes the place for the soul’s metaphors.” In other words, if we can’t make images in art, music or beautiful speech we get sick. Certainly, this is one reason for the huge increase in poetry readings and oral tradition performances such as Rumi’s Caravan. People are hungry for more meaningful – and beautiful – language. For more on this thought, see my essay, Creative Etymology for a World Gone Mad.

But let’s be clear about our situation. There is no reason to assume that indigenous people cannot do this. Actually, it is we who have, by and large, lost this capacity. The curses of modernity – alienation, environmental collapse, totalitarianism, consumerism, addiction and world war – are the results.

We have been living in what Campbell called a “de-mythologized world” for an extremely long time. Literalistic thinking began in patriarchy and blossomed in the victory of monotheism over polytheism. This doesn’t mean that we no longer have myths. Rather, it means that the myths we do have – and we are usually quite unaware of them – no longer feed us. It means that many of us have lost the capacity to think symbolically or mythologically and only have their “toxic mimic,” literal thinking. The most obvious example is fundamentalism, which often replaces metaphor (“This is something else – now go and live with the mystery.”) with parable (“This means that, and only that, so stop thinking.”)

This is unfortunate enough. But the monotheistic world also led inevitably to a world of constant warfare. “Because a monotheistic psychology must be dedicated to unity,” wrote Hillman, “its psychopathology is intolerance of difference.” I offer my thoughts on the religious thinking that resulted in colonialism and empire in Chapter Ten of my book, Madness at the Gates of the City: The Myth of American Innocence, and here are some of the basic ideas:

The western world was beginning to understand myth literally, as actual history. The zealots who wrested control of the early church believed that Christ had physically returned from the dead, and they condemned metaphoric interpretation of his life. Very soon, schisms developed, and rival sects attacked each other in furious jihads. As early as the second century, Clement of Alexandria declared that the gods of all other religions were demons.

The holy text that emerged out of this period omitted the few metaphors of the sacred Earth that had been allowed into Hebrew scripture. As a result, wrote Paul Shepard, the New Testament is “one of the world’s most antiorganic and antisensuous masterpieces of abstract ideology…”

So it should be no surprise that this foundational text of our civilization constantly uses military metaphors. Paul describes Christians as “fellow soldiers.” Timothy uses the soldier as a metaphor for courage, loyalty and dedication. Corinthians is concerned about “an adversary that wants to destroy us…the battle we are fighting is on the spiritual level. The very weapons we use are not human but powerful in God’s warfare for the destruction of the enemy’s strongholds.”  In Thessalonians, Paul employs a military metaphor of a sentry on duty, writing of “the breastplate of faith and love, and as a helmet the hope of salvation.” Ephesians refers to the “armor of God…even when you have fought to a standstill you may still stand your ground.” Similar crusading imagery appears of course in hymns such as Soldiers of Christ, Arise; Onward, Christian Soldiers; the Battle Hymn of the Republic and untold thousands of sermons.

In Thessalonians, Paul employs a military metaphor of a sentry on duty, writing of “the breastplate of faith and love, and as a helmet the hope of salvation.” Ephesians refers to the “armor of God…even when you have fought to a standstill you may still stand your ground.” Similar crusading imagery appears of course in hymns such as Soldiers of Christ, Arise; Onward, Christian Soldiers; the Battle Hymn of the Republic and untold thousands of sermons.

Propagandists, aware that the Roman empire needed a mass ideology to link the individual to the state, took note of this language. It recognized that Christianity, which was re-writing history to de-emphasize its esoteric origins, could fill this role. In the fourth century, it became the official religion of the Empire, the Catholic (universal) faith.  The notion of One True God found its political equivalent in the totalitarian, expansive and ruthlessly violent Roman state. By the fourth century the Church was essentially a branch of government, and it would serve to justify imperial conquests, civil wars, crusades, colonialism and genocidal violence for the next thousand years.

The notion of One True God found its political equivalent in the totalitarian, expansive and ruthlessly violent Roman state. By the fourth century the Church was essentially a branch of government, and it would serve to justify imperial conquests, civil wars, crusades, colonialism and genocidal violence for the next thousand years.

Others were only too willing to turn that violence upon themselves. Christianity became the first religion to make martyrdom a demand of faith. Leonard Shlain put this process into historical context:

Until the Christian martyrs, there does not occur anywhere in the recorded history of Mesopotamia, Egypt, Persia, Greece, India or China a single instance in which a substantial segment of the population accepted torture and death rather than forswear their belief in an ethereal concept.

Missionaries spoke of “taking prisoner every thought for Christ.” In Christian iconography, the knife that Abraham would have slaughtered his son with became a soldier’s sword. The ideal of dying as Christ became dying for Christ which, by the time of the First Crusade, became killing for Christ.

Five hundred years later, the English language, steeped in Biblical imagery, was full of martial metaphors, and Americans would add countless others to their lexicon.

Religious fundamentalists took their Bibles, their racism, their hatred of the body, their violent metaphors and their genocidal conduct to the New World, setting the tone for the development of the myths of American Innocence and American Exceptionalism. Four hundred years on, few of us realize how our language, and hence our thinking, is so unconsciously and deeply flavored by military metaphors.

I don’t need to quote statistics about gun violence and mass murders in America. You’ve all seen them. But the fact that 24% of us, far more than in any European country, believe that “…it is acceptable to use violence to get what we want” also underlies our racist politics, the behavior of our police, and – perhaps you haven’t seen this one – the fact that the American Empire has bombed nearly forty sovereign nations since the end of World War Two.

So: We all need to get more familiar with the metaphorical, symbolic, poetic or mythological language that we will need as the old myths die and we are called to imagine the new ones. And we also need to become more conscious of how, in this de-mythologized world, we use metaphors inappropriately. They can lead to insight, but they can also distort. In creating ways of seeing they can also create ways of not seeing.

Military metaphors are common, for example, in the world of medicine. Though they can promote support for research, they also fuel our American obsession with perfect health, where doctors use the “arsenal of science” as “weapons” to “battle” disease in the “war against the invasion of cancer.” A sick child becomes a “little soldier,” “rallying” to secure victory against the dreaded opponent.

C.S. Lewis described what can go wrong when a “master” uses a metaphor to explain a concept to a “pupil.” The “master” understands the relationship between the literal and figurative meanings, while the “pupil” hears “the unique expression of a meaning” which immediately places a constraint on his thinking. Thus, when physicians use metaphors to explain concepts to patients, the latter are “at the mercy of the metaphor” as it “dominates completely the thought of the recipient whose truth cannot rise above the truth of the original metaphor.”

In Illness as a Metaphor, Susan Sontag wrote that cancer is so embedded in the western psyche that the word itself is weighted with connotations:“…in the popular culture, cancer equals death.” We treat it “as an evil, invincible predator, not just a disease…talk of siege and war to describe disease now has, with cancer, a striking literalness and authority…”  The enemy is not bacteria but “the fanatic…cells” of the patient whose body has become the battlefield. The cancer takes over the body, perhaps physically, but also metaphorically.”

The enemy is not bacteria but “the fanatic…cells” of the patient whose body has become the battlefield. The cancer takes over the body, perhaps physically, but also metaphorically.”

And, I think, most significantly, cancer is “regarded…as a diminution of self.” Readers familiar with my writings may notice the implications for American myth, where the tradition of blaming victims for their own bad fortune is the shadow that lurks behind our Calvinist heritage of predestination, Social Darwinism, positive thinking and the Prosperity Gospel. In other words, the use of military metaphors tends to stigmatize those who are ill and make them feel responsible for the “wrong thinking” that caused their illness – and, by the way, distract them from considering the politics of environmental pollution and lack of health insurance.

This discussion is particularly relevant to the U.S., where we are almost always invading someone else. Indeed, the nation has been at war 93% of the time, 222 out of 239 years, between 1776 and 2015.

So we find military metaphors in nearly any context, as we’ll see below. Cultural anthropologist Robert Myers says that “gun speak,” or “war speak” has permeated American culture so deeply that it’s used by everybody – men and women, Republicans and Democrats, gun owners and people who have never even seen a real gun:

…it doesn’t break down by education or social class…I can’t say that we use this violent language and imagery and that makes us more violent. But I can ask… ‘Well, if we spoke with all kinds of racist words, were we more likely to be more racist or more comfortable being racist?

Myers writes, tongue-in-cheek (I hope) that the warspeak permeating everyday language “puts us all in the trenches, and most of us don’t even know it.” Everything has been “weaponized” – a word which, according to Google’s Ngram Viewer, has increased in print by a factor of 10 between 1980 and 2008. He suggests that warspeak matters for three reasons:

First, it degrades our ability to engage with one another. Framing an issue as a “war” can communicate an urgency that requires instantaneous – and often thoughtless – action.

Second, it evokes violent attitudes. Young adults exposed to political rhetoric charged with warspeak are more likely to endorse violence.

Third, when everything is laden with violent imagery, our perceptions and emotions become needlessly distorted: “Political carnage and carnage in the classroom, weaponized songs and weapons of war, snipers on the hockey rink and mass shooters – all blur together across our cognitive maps.”

Part Two

You can’t wait for inspiration. You have to go after it with a club. – Jack London

Here is a list of martial metaphors (followed by some sports names) that I’ve compiled. Its sheer size, more than any analysis, may help you realize how often you use some of them and why we all need to be conscious of our speech. After that, we can think about alternatives.

Above and beyond the call of duty

Advance

All-out assault

All hands on deck

Armed with knowledge

Ammunition for arguing

Armoring

Arsenal

Attacking my subject

AWOL

Banging

Battle of the Bands

Battle Royale

Battleground states

Bazooka Gum

Beachhead

Besiege

Big guns

Bite the bullet

Blast from the Past

Blitz

Blockade

Blockbuster

Bombshell of a report

Blonde bombshell

Bloodbath

Blow them out of the water

Blown away

(The) Bomb

Bomb (theatrically)

Bombarding with facts

(A) Booming voice

Boot camp for computers; rehab; diabetics; weight loss; etc

Boots on the ground

Break a leg

Bring out the heavy artillery

Broadside

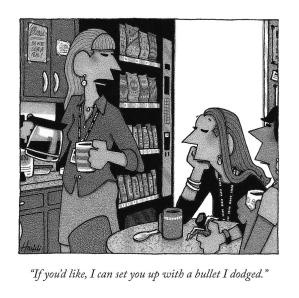

Bullet point; Bullet train; Bulletproof plan; Dodging a bullet

Burning one’s bridges

Call to arms

Camouflage

Canon for an arm

Canon ball dive

Ceasefire

Changing of the guard

Clarion call

Collateral damage

Conquest of nature

Coup de grace

Courageous battle against cancer

Cowboys and Indians

Cowboy up

Crossfire

Crosshairs

Crusade

(A) crush on her

Crushing it

Culture wars

Cutting contest (Jazz)

Deadline

Dead End; Dead Man’s Curve, Hand, Island, etc

Decimated

Deserter

Destroying the opposition

Devastated

Doctor’s orders

Doing some damage

Dressed to kill

Dud

Earning your stripes

Economic Hit Man

Enemy

Fight fire with fire

Firestorm

Firing blanks

Firing line

Flank

Foxhole

Front and Center

Front lines of the debate

Fruits of war

FUBAR

Get us over the top

Go for broke

Half-cocked

Hammered

Happy warrior

Hard-hitting

Hard-liner

Have your back

Hired gun

Hit record; baseball hit; website hit

Hit the mark

Home run blast

Hostile takeover

I love him to death

In the heat of battle

In the trenches

Incoming fire

Invasion of cancer cells

IPO launch

Itchy trigger finger

It’s a losing battle

Join the ranks

Judicial arms race

Kick-ass performance

Killer app

Killing it, making a killing

Knock ’em dead

Knock yourself out

Launched (offspring)

Line in the sand

Lock, stock and barrel

Locked and loaded

Loose cannon

Main thrust of the argument

Man up

Marching as one; together; in unison; in step

March of progress

Marshalling the troops

Miss-fire

Missing in action

Mobilize

Nailed it

No holds barred

No man’s land

No quarter

Nuclear option

(That’s) Over the top

Pass muster

Penetrating insight

Photo bomb

(She’s a) pistol

Police your room

Pounding a beer

Powder keg

Pulverize

Punchline; beat to the punch

Punch it (through a yellow traffic light)

Push comes to shove

Rally the troops

(Corporate) Raiders

Rank and file

Rising up the charts like a bullet

Roger and out

Salvation Army

Salvo

Seeds of destruction

Shot: photograph, basketball, line-drive

(A) shot at success

(Give me your best) shot; (Good) shot!

Shot over the bow; Shot in the dark; Shot down

Shot at fame / love / success, etc

Shots of vodka, tequila, etc

Shoot from the hip

Shoot a text / email

Shoot the moon

Shooting down the opposition, shooting back

Shooting star

Shooters (drinks); Shooters Restaurant

Silver bullet

Slam dunk

Slash emissions

Slay

Smokescreen

Smoking gun

SNAFU

Soldiers of the Lord

Soldier on

Sound off

Spartan(s)

Stand tall

Stick to your guns

Stoned

Sweating bullets

Tackling the problem

Take liberties

Take no prisoners

Taking the internet by storm

Target

Task force

This is my rifle, this is my gun; one is for killing, one is for fun.

This means war!

Three-point bomb

Throw everything we’ve got at this problem

Throwing firebombs

Time bomb

To the hilt

Top gun

Triggering; pulling the trigger; trigger warnings

Troops, trooper

Truce

Tweet bomb

Under fire

Under the gun

Up against the wall

Up in arms

Vaccine shot

Waging peace

War on drugs; cancer; poverty; Christmas

War room

War zone

Warriors (spiritual)

Weaponize

Within striking distance

And a few college sports nicknames:

(ASA College) Avengers

(Ohio Wesleyan) Battlin’ Bishops

(Thomas Moore College) Blue Rebels

(Lutheran Bible School) Conquerors

(Eastern Kentucky) Colonels and Lady Colonels

(Fla. Nat. Univ.) Conquistadors

(Holy Cross) Crusaders

(Dordt College) Defenders

(St. Ambrose) Fighting Bees

(N. Dakota) Fighting Hawks

(Kalamazoo) Fighting Hornets

(Illinois) Fighting Illini

(W. Illinois) Fighting Leathernecks

(Muskingum) Fighting Muskies

(N.C. Arts) Fighting Pickles

(Wilmington Col.) Fighting Quakers (!)

(Carrol College) Fighting Saints

(Ohio Valley) Fighting Scots

(Mary Baldwin College) Fighting Squirrels

(Wash. & Lee) Generals

(McDaniel College) Green Terror

(CA Maritime) Keelhaulers

(Arcadia) Knights; (Army) Black Knights

(Massachusetts) Minutemen

(New England) Patriots

(U. Hawaii) Rainbow Warriors

(Oakland) Raiders

(Texas) Rangers

(Texas Tech) Red Raiders

(Mississippi) Rebels

(UNLV) Runnin’ Rebels

(San Jose St.) Spartans

(USC) Trojans

(Minnesota) Vikings

(Auburn) Warhawks

(Golden State) Warriors

Part Three

Problems cannot be solved at the same level of awareness that created them. – Albert Einstein

These days there is much talk about de-colonizing our minds – interrogating ourselves about the unconscious biases, racist opinions, classist ideas, colonialist language (and, I would add, outmoded mythologies) that we take for granted and that no longer serve us, if they ever did. To this list we need to add de-militarizing our minds. And this requires learning to reframe our metaphors, especially around health and illness.

The Queen of reframing, astrologer Caroline Casey teaches that our military metaphors subtly determine and undermine the metaphysics of our relationships and our work in the world. We’d see both our childhood traumas and our medical crises in very different lights if we viewed them as “our beautiful, dangerous assignments.” Indeed, in discussing her own cancer diagnosis, she speaks of having “inappropriately exuberant cells” that have “no respect for boundaries” and “can’t stop growing.”

Reframing is not necessarily about positive thinking, only adding a poetic mind that may prevent us from feeding the problem. Barbara Ehrenreich writes that separating her cancer, “an evil predator,” and the body in which it resides seems to stand at odds with the nature of the disease. She calls the cancer cells in her body “the fanatics of Barbaraness, the rebel cells that…carry the genetic essence of me.” The cancer then becomes not an enemy, but a part of her, that which is the most fanatical; not a predator but an overzealous fan.

Again, metaphors are the language of poetry, but they don’t have to be so damned serious. Earlier, I quoted Jack London: “You can’t wait for inspiration. You have to go after it with a club.” Another master of reframing, Rob Brezsny, comments:

That sounds too violent to me, though I agree in principle that aggressiveness is the best policy in one’s relationship with inspiration. Try this: Don’t wait for inspiration. Go after it with a butterfly net, lasso, sweet treats, fishing rod, court orders, beguiling smells, and sincere flattery.

They key word as we move on is “relationship.” Casey teaches that whatever we fight against grows stronger because we give it more energy than it originally had. She suggests reframing that phrase to “what we dance with.”

Some of the Asian “martial” arts understand this. Aikido practitioners learn to use their opponent’s own aggressive energy to defeat them, or, ideally, to guide them into a higher state of awareness in which physical violence is not an option. They perceive failure as a point when one succumbs to the temptation of literal violence. Similarly, in other contexts such as couple’s counseling, one attempts to help another person reframe and formulate the question he really wants to ask, to help him get past his own anger or unconscious motives, to not, in poet William Stafford’s words, “follow the wrong god home.”

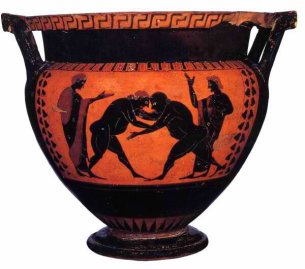

Sumo wrestling referees wait to signal the start of a match until it is clear that both competitors are conspiring (breathing in unison.) This reminds us to go back to etymology for reframing help. Diabolic (“to throw across”) comes from the same root as ballet. The root of “compete” is “petitioning the gods together.” We see this when top athletes sincerely, even lovingly, hug each other after fiercely “engaging” with each other (double meaning intended).

As I’ve shown, so many of the military metaphors in American English are rooted in the New Testament. Some scholars claim that The Book of Revelation is the most popular Bible section among Evangelicals. But etymology is very helpful here too. Apocalypse doesn’t mean “destruction” or “end times,” but rather “to lift the veil.” It was written at the end of the Pagan age, and now the age of monotheism is falling into such literalistic thinking that we can see its own conclusion approaching. At the end of this age we have the opportunity to see truths that have been veiled behind outdated myths.

We need to use sacred language, in the subjunctive mode: pretend, perhaps, suppose, maybe, make believe, may it be so, what if – and play. This “willing suspension of disbelief” is what Coleridge called “poetic faith.” Then, says Lorca, the artist stops dreaming and begins to desire. Love moves from imagination to inspiration, which invents the “poetic fact,” where new life comes not from us but through us.

Jung said that myth offers us two gifts: a story to live by, and the opportunity to disengage or “dis-identify” from outmoded patterns and thus re-engage in a different way with the archetypal energies from which our stories arise. In the tribal world, art (as ritual) serves to balance the worlds of the living and the unseen. Healing comes through memory, both in purging grief and guilt and in creatively re-framing one’s story – what Hillman called “healing fictions.”

It was Memory herself, Mnemosyne, who mated with Zeus and birthed the Muses. Reconnection to memory through art reverses the work of Kronos and counters Time’s linear progress with her cyclic imagination. Ultimately, we heal by re-membering what we came here to do.

It is said that the Muses collected the scattered limbs of dismembered bodies; it was they – art – who reassemble what our military metaphors rip apart.

If we absolutely have to use military metaphors, let’s remember poet Dianne Di Prima: “The only war that matters is the war against the imagination.” How do we reframe “conflict?” There is plenty of evidence that tribal people once believed that conflict existed not only to eliminate alternative voices, but to bring people together. We see vestiges of this in the Gaelic language. One cannot say, “I am angry at you,” but only, “There is anger between us.” I’ve mentioned competition and engagement. Animosity, with its connections to animal, animate, animation and anima, derives from the Latin for “breath of life.” If we follow animosity to its archetypal source, we may find the one breath we all share.

Greek myth provides a surprising image in the war god, Ares, the “killer of men.” Zeus calls him “…most hateful to me.” But beyond the Iliad, he appears in few fully elaborated myths. Instead, wrote Hillman, “He presents himself in action rather than in telling…The god does not stand above or behind the scene directing what happens. He is what happens.”

Like all inhabitants of the polytheistic imagination, Ares is more complicated than he seems. He is an image of the divine, and thus of the psyche. This tells us first that Greek culture understood that martial values are fundamentally human. Second, some say that Ares was taught to dance before he was taught the arts of war.

Third, no monk, he was Aphrodite’s lover. This most masculine god and this most feminine goddess birthed a daughter, Harmonia. Love and war beget harmony, as Psyche and Eros beget Voluptos, or voluptuousness.

Soldiers entering battle invoked Ares, asking for strength and courage. But they also called upon him to prevent conflict from degenerating into uncontrollable violence, as in this ancient hymn:

Hear me, helper of mankind, dispenser of youth’s sweet courage, beam down…your gentle light on our lives…diminish that deceptive rush of my spirit, and restrain that shrill voice in my heart that provokes me to enter the chilling din of battle…let me linger in the safe laws of peace…

Hear me, helper of mankind, dispenser of youth’s sweet courage, beam down…your gentle light on our lives…diminish that deceptive rush of my spirit, and restrain that shrill voice in my heart that provokes me to enter the chilling din of battle…let me linger in the safe laws of peace…

This poetry invites us to imagine a consciousness that loves conflict as a form of relationship, seeking restoration of harmony rather than domination. “Who would have imagined,” wrote Hillman, “that restraint is what Ares offers?” And Aphrodite’s sensual fury is hardly different from that of Aries. Their union is one of sames rather than of opposites, and thus passionate aesthetic engagement can restrain violence. Long-term discipline of an art tames hasty emotional expression but not its passion. Violence is beyond reason; what counters it must be equally unreasonable: “Imagine a civilization whose first line of defense is each citizen’s aesthetic investment in some cultural form.”

If the archetypal warrior is forced into combat, he goes sadly. If he survives and returns, he grieves for all the dead, because he knows that his enemy was a part of himself. In serving the Divine King of the psyche, he is charged with protecting boundaries, with determining which outside elements to welcome and which are dangerous. Invoking him, we reframe “armoring” into “respect for proper boundaries.” In Irish myth the Fianna warriors guarded the borders of the realm and questioned all strangers, “Would you like a poem or a sword?” Let’s imagine shifting the role of the police from controlling and punishing Black people to – artfully – protecting the borders of the realm. The purpose of the entire military could be nothing more than that of the Coast Guard.

An example from biology is the immune system. The skin and lining of the small intestine are semi-permeable membranes that know what to allow in (air and nutrients) and what to keep out (microbes and toxins). In an infection, certain white blood cells sound the alarm, others neutralize the invaders and still others curtail the immune response when the danger is over. Then the body creates antibodies to remember – memorialize – the event and protect against future ones.

Our military metaphors may point to a certain wisdom about our demythologized world. Why, in the most competitive society in history, do “proper,” middle-class people tend to avoid actual confrontation, restricting it to spectator sports? Perhaps we intuitively know that normal social interactions cannot contain conflict and prevent it from turning into literal violence; it simply isn’t safe. Our myth of redemption through violence polarizes us into one of the two most easily assumed stances: the path of denial and/or retreat, or the path of extermination. We inevitably resort to either fight or flight.

Ritual provides a third alternative: staying in relationship without being violent. It requires, however, that participants acknowledge the reality of the Other. In West Africa, traditional Dagara married couples engage in conflict rituals every five days. Agreeing that there will be no violence, each person simultaneously vents all accumulated emotions. The entire village may witness them. Long experience has shown them that conflict causes damage to the entire community only if it is removed from ritual and brought out into the profane openness of daily life.

African American culture abounds in the ritualized conversion of aggression into creativity. Examples include break dancing, poetry slams and “the dozens,” verbal jousting in which antagonists poetically insult each other’s mothers. Mythologist Lewis Hyde writes that the loser is “the player who breaks the form and starts a physical fight…who chooses a single side of the contradiction” between attachment and non-attachment to mother. The winner artfully holds the tension of the opposites.

Characteristically, Rob Brezsny suggests that even this ritual can be reframed:

I invite you to rebel against any impulse in you that resonates with the spirit of “Playing the Dozens.” Instead, try a new game, “Paying the Tributes.” Choose worthy targets and ransack your imagination to come up with smart, true, and amusing praise about them…here are some prototypes: “You’re so far-seeing, you can probably catch a glimpse of the back of your own head.” “You’re so ingenious, you could use your nightmares to get rich and famous.” “Your mastery of pronoia is so artful, you could convince me to love my worst enemy.”

Part Four

Turn this wall on its side and it becomes a bridge! – Graffiti on the Mexican side of the U.S. border wall

Mythopoetic men’s conferences have evolved effective conflict rituals that encourage men to engage with each other on subjects as frightening as race, power and sex without either leaving or becoming violent. In this context, safety means feeling secure enough within the ritual container to take risks. If men remain in this heat of confrontation long enough, they may get past anger to the underlying grief, to weep together and to cleanse their souls.

Joshua Chamberlain was a Union Army general who recorded the awesome spectacle of Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9th, 1865:

Before us in proud humiliation stood…men whom neither toils and sufferings, nor the fact of death, nor disaster, nor hopelessness could bend from their resolve…thin, worn, and famished, but erect, and with eyes looking level into ours, waking memories that bound us together as no other bond…On our part not a sound of trumpet more, nor roll of drum; not a cheer…but an awed stillness rather, and breath-holding, as if it were the passing of the dead! …How could we help falling on our knees, all of us together, and praying God to pity and forgive us all!

He knew as few could know that the two armies, ground down by four years of carnage, had suffered together. Despite the hatred – or perhaps because of it – they had erased a little bit of that sense of otherness that drives men to violence. The surrender, of course, didn’t heal the nation’s wounds, but Chamberlain’s vision invites us into the imagination of reconciliation. Reframing can lead to clarification of intention.

I’ve already alluded to the idea that competition means “petitioning the gods together.”  The ancient Greeks knew this. Agon (the root of agony) was their term for a contest in athletics, horse racing, music or literature. It also referred to a challenge that was held in connection with religious festivals, especially Tragic Drama, in which the two main characters were the protagonist and the antagonist.

The ancient Greeks knew this. Agon (the root of agony) was their term for a contest in athletics, horse racing, music or literature. It also referred to a challenge that was held in connection with religious festivals, especially Tragic Drama, in which the two main characters were the protagonist and the antagonist.

This doesn’t mean that the Greeks were able to transform their greed and their passions into non-violence. Indeed, they were constantly at war with each other. However, almost every four years between 776 BC and 393 AD they called sacred truces. Many scholars see the origin of Olympic competition in earlier funeral games that were held to honor deceased heroes, as described in the Iliad.

So contest can mean “testing together,” or “to bear witness together,” from the Latin testis (plural: testes). Michael Meade claims that “testimony” implied holding one’s hand over one’s testes to prove that he was telling the truth.

So now we can reframe the military metaphor Give me your best shot into “Show me what you’ve got; inspire me to show what I can do,” and then into “Let’s make this boxing match (ball game, breakdance, poetry competition, etc) into the most beautiful thing imaginable!”

Our task is to do more than simply deconstruct outmoded belief systems. They hold us not merely because of generations of indoctrination, but because of their mythic content. They grab us, as all myths do, because they refer to profound truths at the core of things, even if those truths have been corrupted to serve a culture of death. We cannot simply drop them by realizing that they are myths; we must go further into them, by telling the same stories, but reframing them until we discover their essence.

Americans have some advantages here. Our fascination with the new masks our anxiety about the present, our grief at how diminished our lives have become and our fear of being erased in a demythologized future. But it also awakens the archetypal drive to slough off old skin and be reborn into a deeper identity.

As Casey says, “co-operators are standing by.” The other world is offering help, but indigenous protocol insists upon our full participation. We will develop that capacity as we build our willingness to imagine. This is why the renewal of the oral tradition is so important; it enables us to go beyond the literal and think metaphorically. Here are a few ideas from Chapter Twelve of my book:

We can start by reframing capitalism’s basic – and bizarre – superstition that if each person pursues his own narrow interests, then the common good advances. Instead, let’s imagine a society in which individuals enhance both their own wellbeing and the greater good only when they give fully of themselves. This implies an indigenous concept of abundance in which the role of money is to facilitate the transition of value from its source in the Other World to its recipients in this world, and back. Wealth is a warehouse in transit, temporary storage. As in a potlatch, one accumulates it in order to give it away.

Appreciation of interconnectedness reminds us that we both held by and accountable to the larger communities of nature and spirit. Dominion can become stewardship or husbandry, which can free us from our mad obsession with growth. Then we can replace the GDP with a “Gross National Happiness” index.

We can replace development with liberation (from Liber, Dionysus) in both its Buddhist and political senses. Then our obsession with growth will be unmasked as a spell that monotheistic thinking has cast over the indigenous soul. Liberation: breaking the spell, lifting the veil. In America, the shadow of growth (both economic and spiritual) is depression. But in previous depressions we learned to stop buying things we didn’t need. We can do it again, as a simple solution to consumerism and pollution. The opposite of consumption is neither thrift nor poverty but generosity.

Below the pressure to compete lie older assumptions. The vindictive God of the Old Testament never seems to have enough blessing for everyone. Is this why we strive so hard to accumulate things? Let’s reframe scarcity and original sin into infinite fecundity and original blessing.

Scarcity assumptions (if there is not enough to go around, then only the “elect” will have it) lead to Puritanism. Let’s reframe the compulsion to work unceasingly into the drive to remember and deliver our unique gifts. Finding a sense of belonging from what we give rather than from what we get will free us from blaming capitalism’s victims for their own suffering. With less energy invested in success, we’d find less shame in failure. Idleness would transform into the opportunity to do more important things than make money. Self-improvement could become a non-dogmatic, communal spiritual quest. Perhaps addictions stemming from our misguided search for meaning and a true home in the world would simply melt away. Then self-interest and individualism would shift eventually to the needs of the soul and prosperity would not be measured in numbers.

We would reframe Puritanical contempt for the body into an inclusive, humorous eroticism. Heterosexuals would appreciate gay people as gatekeepers. We could shamelessly entertain images of lust and loss of control without needing to project them upon others. The paranoid imagination would lose its suffocating grip on our emotions, as we reframe anxiety itself into the natural curiosity and hospitality of people who know who they are.

We would reframe Puritanical contempt for the body into an inclusive, humorous eroticism. Heterosexuals would appreciate gay people as gatekeepers. We could shamelessly entertain images of lust and loss of control without needing to project them upon others. The paranoid imagination would lose its suffocating grip on our emotions, as we reframe anxiety itself into the natural curiosity and hospitality of people who know who they are.

Perceiving abundance in spiritual terms, we’d also reframe the predatory imagination. Entertaining the possibility that we are held by non-human powers, we would find no joy in exploiting others. Feeling welcome in the world, we would laugh at primitive ideas like dog eat dog or every man for himself.

The earth needs real heroes like never before, but we will prefer peace heroes to war heroes. As we support ritual containers for the initiation of youth, we will no longer be fascinated by men who risk their lives crushing the Other to restore the peace of denial. We will applaud those who commit to the hard work of relationship with the feminine, men who don’t ride off into the sunset.

Reframing heroism will help us take back what we have projected onto entertainers. We will still admire those who excel in athletics, public service and the arts as models for excellence. But as the images of the pagan divinities return, as we understand them as aspects of our own souls, the cult of celebrity will wither away.

We could drop the patronizing moral superiority that justifies interventions and invasions (both international and interpersonal), transforming them into the desire to encourage (give heart to) the best in people, to see others find their own voices. As patriotism shrivels back into love of the earth – matriotism – racism and witch-hunting would transform into appreciation of diversity. And we could shift from “We are not them” into the positive Mayan greeting, “You are the other me.”

Instead of meaning personal fulfillment unimpeded by government, freedom would imply public commitment made possible by government. We would replace the white bread melting pot with a new metaphor reflecting the diversity of soul and world: a polychromatic mosaic of shining ethnic facets, each reflecting all the others.

The world would still be a “vale of soul-making,” as Keats wrote, but it would no longer be a fallen world. Imagine millions of Americans no longer interpreting Biblical poetry as literal fact. Belief would return to its German roots where it is connected to love and cherish. Dropping the model of a god who sacrifices himself to redeem others, we would happily redeem ourselves. Imagine shifting our paranoid confrontation with the Other to the environmental crisis, a stance in which everyone would be “we,” united in the defense of the Earth, when national borders would dissolve.

Sacrifice would revert to its original meaning: voluntary approach to the underworld for the renewal of self and community. It would imply the intimate connection between death and rebirth that constitutes initiation. What is “made sacred” would once again be the person who endures the terrifying ego death that precedes the birth of a new identity. Jung writes, “What I sacrifice is my own selfish claim, and by doing this I give up myself.”

The sacrifice of Isaac – our most fundamental mythic narrative – would once again symbolize the offering up of Abraham’s own innocence.

The sacrifice of Isaac – our most fundamental mythic narrative – would once again symbolize the offering up of Abraham’s own innocence.

Happy to sacrifice what we don’t need, we would reassess consumerism. We would shift from consuming culture (passively ingesting electronic media) to making culture. We would no longer settle for sitting passively while the burdens of our unfulfilled lives get resolved electronically.

Making culture means dropping the need for divertissement (being diverted), performance (to provide completely) and amusement (related to the Muses). We’d create real entertainment (holding together). We would periodically renew ourselves through shared suffering – and shared ecstasy. In return, the art we would make would hold us all together.

Shared ecstasy: a few tastes of the potential of real community would make us realize how little we have been willing to settle for. We would reframe the pursuit of happiness – a deeply constrained vision typical of our narrow emotional range, which is itself the expression of the refusal to grieve – into the pursuit of joy, and of our true natures.

Those who can grieve together can laugh together. Re-acquainting ourselves with the old rituals of grief and closure, we would reframe our characteristic denial of death and come to value the final initiatory transition endured by people who have lived real lives. Death – as a necessary, periodic restructuring of identity – would become our friend, sitting (as Carlos Castaneda wrote) on our right shoulder, reminding us to pay attention to the fleeting beauty of the world. And we could reframe the old question of the generals, What are you willing to die for? into the initiatory challenge, What are you willing to fully live for?

Reframing our reflexive use of military metaphors can help us muse poetically about what is approaching if we could only recognize its song. Time/Kronos vs. Memory/Mnemosyne. From this perspective, we could read our history as a baffling, painful, contraction- and contradiction-filled birth passage in which the literal has always hinted at the symbolic.

If America remembered its song as This Land Is Your Land rather than as Bombs bursting in air, we might understand freedom as willing submission to the soul’s purpose, and liberty as the social conditions that allow that inner, spiritual listening to happen. Diversity and multiculturalism would reflect the vast spaces of the polytheistic soul, and conflict would be about holding the tension of two opposites to create a third thing, something entirely new. We would remember that self-improvement is really intended for service to the communal good, and that individualism points us toward our unique individuality.

Remembering its song, America would remember its body – Mother Earth. Connecting in this sacred manner to the land would naturally lead to rituals of atonement for the way we have treated her, and to a revival of the festivals that celebrate the decline of the old and birth of the new. New Year’s Day could become a national day of atonement – a Yom Kippur – to acknowledge our transgressions and our willingness to start anew. On Independence Day (now Interdependence Day), we would reaffirm that such a start requires the support of the larger community of spirits and ancestors.

Remembering America’s song would allow us to overcome our shameful contempt for our own children and to see them for who they are, rather than as projection screens for adult fantasies of innocence. We could reframe our national narratives with their deadly subtexts of child sacrifice into stories of initiation, renewal and reunion with the Other.

If we saw ourselves in this light – not the direct sunshine of innocence, but the dim glow of an old campfire – we would understand our addiction to violence and those military metaphors as a projection of that initiatory death (that we secretly desire) onto the world, and onto our children. We would withdraw those projections, putting them back where they belong.

We would realize that an appropriate metaphor has already arisen out of this land: the spirit of Jazz improvisation. When Charles Mingus heard a band member play a crowd-pleasing solo, he’d shout, “Don’t do that again!” By this he meant that the sideman needed to keep experimenting, to push himself (and the band) to even deeper soulfulness. And this means not just playing but communicating. Wynton Marsalis explains:

… to play Jazz, you’ve got to listen (to each other). The music forces you at all times to address what other people are thinking, and for you to interact with them with empathy…it gives us a glimpse into what America is going to be when it becomes itself.

We might realize that we have already dropped our fascination with evil. As in the Aramaic, we would view destructive behavior as unripe, as a cry for help, and we would know compassion.

Finally, we could cook innocence itself down to its roots. Our own light would no longer blind us. Innocence, once again, would signify the most basic of all mythic ideas: the new start. Then America could offer the song that the world has always seen in us: not that of a consumer paradise, a destructive adolescent or a wrathful father, but of the ancient story about what makes us human, the rare and lucky opportunity to accomplish what we came here to do.

Richard West, Director of the National Museum of the American Indian, proclaimed at its dedication ceremony, “Welcome to Native America!…The Great Mystery…walks beside your work and touches all the good you attempt.”