In 2014, long before the 2020 economic collapse, a friend forwarded this BBC News article: “American Dream Breeds Shame and Blame for Job Seekers”,which cited statistics claiming that 10.5 million Americans were unemployed. But in practical terms she was quite inaccurate. This was merely the number of people who were collecting weekly unemployment compensation checks.

If we were to add in those who wanted full-time jobs but could only find part-time work (including those working more than one job) and those who had given up looking for work – the actual figure was easily twice that amount (and far higher for people of color).

Why had so many Americans given up? The article continues:

Experts tell the BBC that job seekers in the US are now, more than ever, blaming themselves for being out of work…A study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology last year found that the higher people perceived their social class to be, the more likely they were to believe that success comes to those who most deserve it…(but) Perhaps more tellingly, those of lower status were viewed as unworthy.

Another researcher quoted in the article compared unemployed Israelis with Americans:

Even though Israeli job seekers faced the same relative obstacles to finding work, they saw the down economy and a lack of jobs as an arbitrary, “screwed up” system…Israelis believed that if they kept up the hunt, eventually their number would come up…But not Americans. They experienced a “more insidious and deep kind of discouragement” in which lost job opportunities were personal failures, he says…And because they thought it was their fault, they were more likely to stop trying.

He might as well have compared Americans to workers in any other country. Americans are truly exceptional in this regard. However, neither the author nor any of the social scientists he quoted realized that this is, at bottom, a mythological and even a theological issue.

America’s dual heritage of Puritanism and individualism remains firm in two exceptional beliefs about personal responsibility. The first is the preposterous and demonstrably false idea that the rich succeed without government help, that successful people pull themselves up by their own bootstraps.

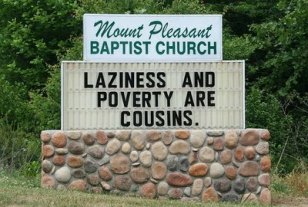

The second is that so poverty is one’s own fault. Most of our media gatekeepers have passively assumed this idea as truth, even if the more superficial, liberal philosophy of equality prevents them from trumpeting it. Others, less shameful, have felt no such restraints.

Back in Ronald Reagn’s 1980s, Jerry Falwell, second only to Billy Graham as America’s best-known preacher, had scolded the poor with this essential American statement: “This is America. If you’re not a winner it’s your own fault.” In 2011, Herman Caine, who would briefly be the Republican front-runner in 2016, said the same thing: “Don’t blame Wall Street, don’t blame the big banks. If you don’t have a job, and you’re not rich, blame yourself.”

Before you go hating Republicans and think that Democrats (or at least the corporate lobbyists who control the party) are fundamentally different, please consider that this is not a Republican/Democrat issue. To believe so is to fall into the liberal version of the myth of American innocence. Almost our entire national political class of pundits and politicians – almost anyone in real power – has shown their willingness to manipulate this situation. It was Bill Clinton (supremely popular, God knows why, among African-Americans) who bragged about ending “welfare as we know it” in 1996.

In a world where the brutal realities of elimination and outsourcing of jobs and corporate control of both media and politics, one might well ask, where do they get this nonsense? The source of this problem, however, is more complicated than mere political cynicism, and more fundamental to our mythology.

Unlike the working classes almost everywhere else, the American poor seem to believe this thinking nearly as strongly as the rich do. A 2017 poll found that 52% of practicing Christians strongly agree that the Bible teaches “God helps those who help themselves.” In Chapter Nine of my book Madness at the Gates of the City: The Myth of American Innocence, I write:

And the ultimate American statement was made by Ben Franklin, not Jesus: “God helps those who help themselves.”…(even) Prior to the economic meltdown of 2008, four million children were suffering merely because they were living with unemployed parents. Yet six out of seven of us believe that people fail because of their own shortcomings, not because of social conditions.

I haven’t seen any relevant statistics about this kind of thinking since the pandemic began, but given that some seventy thousand Americans per year were already killing themselves by overdosing on opioids, I doubt if it has changed much.

Here is the essential American truth: our politics and our economics have a profoundly religious underpinning. Five hundred years after Martin Luther, we still hold to a thinly veiled, reframed philosophy of Calvinist predestination. And the fact that we rarely examine this idea indicates to me how we take it, like all mythological assumptions, for granted.

At the very core of our national mythology is the belief that both the rich and the poor exist not because of a profoundly inequitable, man-made system – capitalism – but because of their own individual merit, or lack of it. Uniquely in all the world, we still believe that wealth and the sense of entitlement that comes with it remains an indication of being in God’s good graces, and poverty is the sign of one’s own individual state of damnation.

America has long enshrined a dualistic, “either-or” thinking that ignores the complicated and tragic nuances of history. Everything that a white, male American learns from very early childhood is that it his destiny to become a hero – a productive, creative, forward-thinking, radically independent and individualistic winner in the game of life. And he also learns, in a thousand subtle ways, that in such a zero-sum world, the only alternative to the hero is to be a loser or a victim.

This belief carries the power of myth because we subscribe to it without ever examining its contradictions. It is one of the characteristics of the Paranoid Imagination. As I write in Chapter Seven, “The paranoid imagination combines eternal vigilance, constant anxiety, obsessive voyeurism, creative sadism, contempt for the erotic and an impenetrable wall of innocence.” You can read Chapter Seven in its entirety online, here.