Part One

For where there is dance, there also is the Devil. – St. John Chrysostom

Bobo-malay, shushu maya (Lord, make this body dance!) – Dagara, West Africa

The Greek word xenos means both “stranger” (as in xenophobia) and “guest.” This etymological twist lies at the root of a profound mystery. As Carl Jung taught us, the repressed or marginalized parts of our souls and our culture desire to return home – and they warn of the long-term consequences of not being welcomed back out of the shadows into the light. This is Depth Psychology’s most fundamental insight, and it invites us into the mystery of healing, both personal and collective: unconsciously, those within the pale also long for that moment of completion, because the body understands what the mind represses.

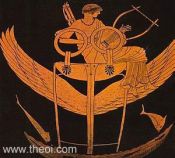

Xenos appears in the fifth century B.C. as the word that the tragic playwrights, especially Euripides  in his play The Bacchae, used to describe Dionysus – the god of wine, of madness, of drumming and ecstatic dance, the ultimate outsider from the mountains, the Other. Throughout Greek myth, Dionysus is contrasted with his rational, heroic half-brother Apollo,

in his play The Bacchae, used to describe Dionysus – the god of wine, of madness, of drumming and ecstatic dance, the ultimate outsider from the mountains, the Other. Throughout Greek myth, Dionysus is contrasted with his rational, heroic half-brother Apollo,  related to the sun, counsellor to Zeus, god of the ruling elites, of calming music, the ultimate insider. Apollo could send healing from the sky, but he could also send death on his heavenly arrows. And unlike Dionysus, he never married.

related to the sun, counsellor to Zeus, god of the ruling elites, of calming music, the ultimate insider. Apollo could send healing from the sky, but he could also send death on his heavenly arrows. And unlike Dionysus, he never married.

These ancient stories are neither untruths, in our conventional use of the word “myth,” nor, by being very old, are they irrelevant to modern culture and politics. We are talking about race relations in America.

All white people who take their sense of identity from the myth of American innocence know deep in their bones, below their prejudices and naïve idealisms, that the road to healing involves transforming xenos from stranger to guest. After visiting the United States, Jung observed,

When the (white) American opens a…door in his psychology, there is a dangerous open gap, dropping hundreds of feet…he will then be faced with an Indian or Negro shadow.

Our American narratives – the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves – have inherited the European divorce of consciousness from flesh that began in Biblical times and metastasized in the Protestant Reformation and the industrial revolution. They maximize individualism, conflict, materialism and competition, while minimizing aesthetic, sensual and ecological interrelationships. They speak of a god (with no wife) and his son who love humanity yet remain aloof, except for their furious judgement of our limitations.

Whether they appear to originate in religion, economics, science, nationalism, consumerism or the culture of celebrity, these stories of detached, rational, progressive, productive, masculine, heroic consciousness arise from a mind that has discarded large parts of itself and condemned them to the shadow worlds. Psychologist James Hillman called this thinking Apollonic: “…like its name sake…it kills from a distance (its distance kills).” Claiming objectivity, “it never merges with or ‘marries’ its material…” It defines our “very notion of consciousness itself.”

Since Colonial times, white Americans, like the ancient Athenians they modeled themselves upon, have seen themselves as Apollonian, hardworking, rational, competitive, progressive, individualistic lovers of freedom. Below the dominant stories, however, our Dionysian shadow, the “Other,” appeared in a form the Greeks would have recognized but burdened with a Christian sinfulness that would have been unfamiliar to them.

The descendants of African slaves, in both their stereotyped, earthy physicality and the implied threat of their vengeance, have always been America’s dark incarnation of Dionysus, its collectively repressed memory and imagination. Since, however, whites desperately needed to project him, to see him, they created exactly those conditions – segregation and discrimination – that dehumanized him and fostered behavior that whites could then proceed to demonize without guilt. And their Puritan heritage justified this process by turning the old beliefs about original sin into an explanation of the causes of suffering. One suffered because one deserved to suffer.

The process of projection through which the ego or the dominant elements in a society create their image of the Other is not logical. As with archetypes, when we constellate one pole of a stereotype, we also conjure its opposite. Since whites needed to believe that blacks were slow, dumb and happy, many blacks learned to act that way. Whites created fictional characters – from Jim Crow to Gone With the Wind’s Mammy: loveable and loyal, yet lacking any concern for intellect or freedom.

A second aspect of the Other in the racist mind contradicted the first. Even as many whites perceived blacks as lazy (a terrible offense to our Puritan heritage), they also perceived them as unable to control their desires (an even worse transgression). Again, since whites needed to see their projection of this intensely sexual and aggressive Other in the world, their gatekeepers in business, religion and government created precisely the conditions that would manifest it: a segregated, hierarchical economy, highly limited opportunities for employment, proliferation of both guns and drugs, and a school-to-prison pipeline.

Since the beginning of large-scale (this is to say, mandatory) public education in the 1890’s, all Americans have learned to be unquestioning cogs in capitalism’s machine. And simultaneously, our religious instructors have presented images of both a meek and desexualized Christ and his furiously vengeful father. Quite naturally, the mind desires to revolt against such a diminished imagination. But when such thoughts are unacceptable, they fall back into the personal and collective unconscious. And when opportunistic politicians offer whites such polar-opposite stereotypes of blacks as laziness and aggressiveness, they find fertile – and familiar – soil in the American imagination. As I write in Chapter Four of my book Madness at the Gates of the City: The Myth of American Innocence:

Othering is inconsistent. Europeans projected opposing images upon Jews: “id” figures who would sexually pollute Christian blood, and stingy, “superego” bankers, unwilling to assimilate…Richard Nixon warned of both “the forces of totalitarianism and anarchy…” During the 1991 Supreme Court confirmation hearings for Judge Clarence Thomas, right-wing senators alternatively accused Anita Hill as being either a spurned woman – or a lesbian. Such discourse doesn’t care whether the terms of othering are logical or not. Any demonizing narrative will do.

The psychological truth that fear, hatred and envy are very close to each other is most evident in the gruesome rituals that Southern racists perpetrated for 200 years. In 1966 African American sociologist Calvin Hernton wrote that the image of the black sexual beast was so extreme in their minds that they had to eradicate it, yet so powerful that they worshipped it:

In taking the Black man’s genitals, the hooded men in white are amputating that portion of themselves which they secretly consider vile, filthy, and most of all, inadequate…(they) hope to acquire the grotesque powers they have assigned to the Negro phallus, which they symbolically extol by the act of destroying it.

These attitudes have never characterized only the lower classes. Those being vetted to become their managers and those born into even higher privilege also had to be indoctrinated. It was necessary for everyone’s innate social conscience and human solidarity to be eradicated, and gatekeepers in higher education made sure of this.

William Dunning, founder of the American Historical Association, taught Columbia students that blacks were incapable of self-government. Yale’s Ulrich Phillips claimed that slaveholders did much to civilize the slaves. Henry Commager and (Harvard’s) Samuel Morison’s The Growth of the American Republic, read by generations of college freshmen, claimed that slaves “suffered less than any other class in the South…The majority…were apparently happy.” In 1915 Woodrow Wilson, formerly President of Princeton, showed Birth of a Nation at the White House, giving semi-official sanction to the movies’ first mega-hit. By depicting heroic white men saving young women from their drooling black abductors, it led immediately to the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan.

In America, the mind/body division coincided with the racial gulf, and this distinction became so sacred, if unnatural, that it required the construction and perpetuation of an elaborate myth of white innocence and national exceptionalism. The Puritan heritage determined that whites were repulsed by the body’s needs and feared that they might be judged by how well they controlled them. Their hatred of the black Other revealed the envy that lay just below the surface, and their unconscious desire to be healed of this deadly burden. Here is a clue to slavery’s appeal that extends beyond economics. This terror, writes journalist Michael Ventura in his brilliant essay Hear That Long Snake Moan, “…was compacted into a tension that gave Western man the need to control every body he found.”

We would never, never allow Negroes to starve, to grow bitter, and to die in ghettos all over the country if we were not driven by some nameless fear that has nothing to do with Negroes…most white people imagine that (what) they can salvage from the storm of life is really, in sum, their innocence.

Part Two

In slavery, writes Ventura, “the body could be both reviled and controlled.” Baldwin was describing what I call the myth of American innocence, the collection of narratives and images that have allowed most of us to live with the realities of race and empire and yet believe that America has a divinely inspired mission to bring freedom and opportunity to the whole world. Yet, strangely, it is possible that the unforgivable enslavement of millions of black people actually initiated a profound, if exceedingly slow, healing process. Compounding this colossal irony, the individuals most responsible came from America’s most bigoted region.

Southern whites reacted with extraordinary violence (committing well over 4,000 lynchings between 1890 and 1930) when blacks attempted to move into the mainstream of life. Shameful as this period was, however, it brought out both our most feared contradictions as well as the seeds of renewal. For all its sorrows, the twentieth century saw several brief periods when forms of Dionysian madness seized the Apollonian mind in its flight from the body and pulled it back to Earth. These periods fundamentally altered America and began to clean out the festering wounds underlying Puritanism, materialism and our national obsession with violence. What did this? African American music.

Throughout the Jim Crow era, the spirit of Africa survived in such folk traditions as Hoodoo  and the Haitian influence in New Orleans, but primarily in the black church. Even though many of its members absorbed the conservative social values of their former masters, there was no mind-body split in the practice of their religion. But this created a bind that Southerners, both white and black, have been in for generations, writes Michael Ventura: “A doctrine that denied the body, preached by a practice that excited the body, would eventually drive the body into fulfilling itself elsewhere.” The call-and-response chanting and rhythmic bodily movement typical of southern preachers absolutely contradict their moralistic sermons. This contributes to “the terrible tension that drives their unchecked paranoias” (to which I would add their unchecked sex scandals).

and the Haitian influence in New Orleans, but primarily in the black church. Even though many of its members absorbed the conservative social values of their former masters, there was no mind-body split in the practice of their religion. But this created a bind that Southerners, both white and black, have been in for generations, writes Michael Ventura: “A doctrine that denied the body, preached by a practice that excited the body, would eventually drive the body into fulfilling itself elsewhere.” The call-and-response chanting and rhythmic bodily movement typical of southern preachers absolutely contradict their moralistic sermons. This contributes to “the terrible tension that drives their unchecked paranoias” (to which I would add their unchecked sex scandals).

Music, whether sacred or secular, held rural communities together by providing a safety valve from the stifling pressure of rigid conformism. Those who most exemplified this paradox were the traveling singers who mediated between the community’s sentimentalized idea of itself and the forbidden temptations of the outside world.

Were these men mere entertainers, or did they serve a necessary role as messengers from the unknown? In The Spell of the Sensuous, Philosopher David Abram observes that in tribal cultures, shamans rarely dwell within their communities. They live at the periphery, the boundary between the village and the “larger community of beings upon which the village depends for its…sustenance.” In terms of indigenous spirituality, these intermediaries ensure an appropriate energy flow between humans on the one hand, and ancestors, spirits, plants and animals, or (to reduce things to psychology) unconscious aspects of the personality, on the other.

The Greeks imagined that the boundaries were the realms of Hermes — and of Dionysus. Hillman writes,

In Dionysus, borders join that which we usually believe to be separated by borders…He rules the borderlands of our psychic geography.

In 1920, the South was still a primarily rural society with a living folklore that extended back to Ireland, Scotland, Haiti, Jamaica and especially Africa. For this reason, and despite all its feudal horrors, its people retained a vestigial memory of the permeable boundaries between the worlds; and it was the singers, preachers and storytellers who mediated the edge.

By contrast, the urban North was characterized by the crowded, dirty, noisy, mechanized life of factories and tenements (for the poor) and the unrelenting drive for money and status powered by the Protestant Ethic (for the middle-class and rich), and they paid a considerable price in alienation from the natural world. Modern life, writes Greil Marcus, “…had set men free by making them strangers.” Existence in the urban factories had diminished human passions in favor of a reserved, cynical, blasé attitude. This had created a compensatory craving for excitement and sensation, which for some was partially satisfied by city life. But others needed something more extreme, more Dionysian, to make them feel alive.

This damage to the soul occurred along with the most rapid technological changes in history. The all-encompassing verities and authority of religion had been, to a great extent, replaced by nationalism. One Frenchman fated to die in the first weeks of the Great War observed that the world had changed more since he had been in school than it had since the Romans. In the thirty years between 1884 and 1914, humanity had encountered mass electrification, automobiles, radio, movies, airplanes, submarines, elevators, refrigeration, radioactivity, feminism, Darwin, Marx (who wrote, “All that is solid melts into air”), Picasso – and Freud.

What irony: just as the modern world was learning of the unconscious, it was about to embody the ancient myths of the sacrifice of the children. The pace of technological change simply exceeded humanity’s capacity to understand it, and the pressure upon the soul of the world exploded into world war. For four years in Europe, between seven and ten thousand people, mostly young men, were killed or died of starvation, every single day. And then the Spanish Flu decimated millions. Even though the violence did not reach American soil, the pandemic and the grief certainly did. We can never know the extent of trauma this generation experienced.

After the Great War, the anxieties and economic pressures of the new century threatened to overwhelm the small-town values of self-denial, strict moral conduct and racial exclusion in the South. Great political rifts were growing that would eventually explode in the 1960s. Thousands of black veterans returned, mostly to the South, and women were about to achieve the right to vote, just as city dwellers were becoming the majority of the population. 1919 – “Red Summer” – saw 3,600 strikes  involving over four million workers. But it also saw over 25 race riots (all of them white-on-black), the Palmer Raids (dedicated to destroying the Red “Outer Other”) and the resurgent Klan (obsessed with the black “inner Other”).

involving over four million workers. But it also saw over 25 race riots (all of them white-on-black), the Palmer Raids (dedicated to destroying the Red “Outer Other”) and the resurgent Klan (obsessed with the black “inner Other”).

And something completely new arose. The average age of the onset of puberty was decreasing while the average age at marriage was increasing. Adolescents began to find themselves in a prolonged period of dependence upon their parents, who first used the word “teenage” around 1920.

As the pace of change led to drinking rates that have not been equaled since, religious reactionaries compelled the government to declare Prohibition. Until 1933, it would be illegal to sell or transport intoxicating beverages. America, alone among industrialized nations, declared that the celebration of Dionysus (whom the Greeks knew as Lusios, “the Loosener”) in even this most literal form was unacceptable. But the repressed quickly returned; sixty percent of the public continuously violated the law. “Dionysus,” wrote psychologist Raphael Lopez-Pedraza, “took his revenge in bootlegging, gangsters and violence.” The word “underworld” now referred to organized crime, rather than the abode of the ancestors. It still served as a mirror of the upper world, but now of its rapacious capitalism. Instead of a revival of Protestant asceticism, America experienced the “roaring twenties.”

Politically and economically, African Americans remained on the periphery of the American story. But something else new – and critical – arose. New technology brought their culture into the mainstream. In a sense, technology, easily accessible (in the form of records and sheet music) and even free (in the form of radio), gave American culture a permission it had not had before, except through alcohol and violence. Soon, everyone was dancing;  indeed, “the Charleston” dance craze was actually a West African ancestor dance. People (at least urban people) began to speak openly about sex, gender and the body’s demands for pleasure. And everyone watched movie images of other people’s bodies experiencing pleasure in this period before the introduction of the Motion Picture Production Code.

indeed, “the Charleston” dance craze was actually a West African ancestor dance. People (at least urban people) began to speak openly about sex, gender and the body’s demands for pleasure. And everyone watched movie images of other people’s bodies experiencing pleasure in this period before the introduction of the Motion Picture Production Code.

There were signs that the white ego was loosening up. Psychologist Stephen Diggs writes that this “alchemical process” melded western individual consciousness with tribal orality: “Where the Northern soul, from shaman to Christian priest, operates dissociatively, leaving the body to travel the spirit world, the African priest, the Hoodoo conjurer, and the bluesman ask the loa to enter bodies and possess them”.

Still, the Klan claimed four million members. In 1921, whites destroyed the black section of Tulsa, killing 300 blacks. In 1923, they destroyed the black town of Rosewood, Florida, killing dozens. It was a particularly cruel irony. Even as whites were experimenting with tentative rejection of their ancient hatred of the body, they were – savagely – punishing people who (to them) seemed to exemplify natural comfort in that body. But Blacks were now in a uniquely influential position. Even as they suffered continued segregation and repression, their music (at least watered-down versions of it) was challenging the white majority’s most fundamental beliefs.

Students of myth will recall that (in The Bacchae, by Euripides) the young King Pentheus was both revolted by and attracted to his cousin Dionysus. This story reminds us that fascination always lies just beneath hatred of the Other, because the Other is an unrecognized part of the Self. America played out much of its love-hate relationship with its Dionysian shadow throughout the twentieth century on the field of popular music.

This process has moved in a dialectical series of cultural statements, an insight first proposed by LeRoi Jones (later known as Amiri Baraka) in his seminal book Blues People: Negro Music in White America. To simplify: blacks merge western techniques with indigenous African traditions to create new musical styles. Whites (such as Paul Whiteman) copy it, dilute its intensity and proceed to reap most of the profits. Then younger blacks create a revitalized

musical expression, but this time with the intention of restoring black identity, as a conscious choice to remain outside.

musical expression, but this time with the intention of restoring black identity, as a conscious choice to remain outside.The message, “We are not like you” is a statement about otherness, for once, by the Other, which prefers exclusion if the result is the survival of authenticity. In a culture that elevates the dry, masculine, Apollonian virtues of spirit over the wet, feminine and Dionysian, blacks would begin to use the word soul in 1946 to define their music in contrast to the dominant national values. Eventually other terms – soul brother (1957), soul patch (1950s), soul food (1957) soul music (1961) and soul sister (1967) – would arise in proud contrast to the dominant national values.

Again, white adults copy the new forms, removing their most Dionysian elements to make them more acceptable. But white youth typically prefer the real thing, inviting xenos, the stranger, to become the guest. From Dixieland to Hip-Hop, the cycle has repeated itself for nearly a century.

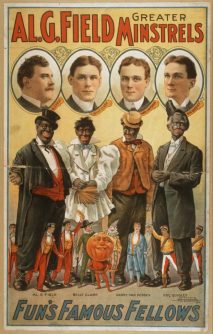

Xenos. In this twisted yet profoundly important dialogue, whites have consistently feared contamination by the stranger (black people), yet they desperately long for the emotional and bodily freedom offered by the guest (black culture). This is an essential aspect of whiteness itself. “The white itch to affect blackness,” writes Kevin Phinney, “is an ineffable part of the American experience.”  Indeed, blackface minstrelsy had been America’s primary form of entertainment throughout much of the nineteenth century. Forms of it (Amos ‘n Andy, originally voiced for radio by two white actors) would survive into the 1950s, tutoring millions in racist stereotyping. But it provided something else: by watching other whites impersonating blacks, whites could briefly inhabit their own bodies.

Indeed, blackface minstrelsy had been America’s primary form of entertainment throughout much of the nineteenth century. Forms of it (Amos ‘n Andy, originally voiced for radio by two white actors) would survive into the 1950s, tutoring millions in racist stereotyping. But it provided something else: by watching other whites impersonating blacks, whites could briefly inhabit their own bodies.

But popular thinking still remains polarized along racial lines: civilized vs. primitive, abstinence vs. promiscuity and sobriety vs. intoxication, all forming the opposition between composure and impulsivity (mythologically, Apollo and Dionysus). For generations, power elites have manipulated the fear that those who cannot control their desires will tempt the majority to follow them, that no one might resist temptation. In the white collective unconscious, the black man is America’s Dionysus, coming to liberate the women, to lead them to the mountains so that they might dance, free of patriarchal control.

And in this liberating, loosening, archetypal (yet terrifying) role, the mad god offers men two choices. The first is to accept these changes, drop your own stiff, heroic, detached consciousness and dance with us.

Every child has known God,

Not the God of names, not the God of don’ts,

Not the God who ever does anything weird,

But the God who knows only four words

And keeps repeating them, saying:

“Come Dance with Me.” Come Dance. — Hafiz

Or, like King Pentheus, who refuses the invitation, be torn apart.

Part Three

Just as Prohibition ended, Hollywood agreed to censor itself and suppress the erotic. Walt Disney attained huge popularity with his sanitized, asexual cartoons. In his movies, write Robert Jewett and John Lawrence, “Sex had become sufficiently innocent, trivial…that every family knew it could trust itself to go to the movies.” It was a kind of mass compromise between Puritanism and opportunism. America traded away one mild manifestation of the Pagan sensibility (Aphrodite in the movies) to get another (Dionysus) back in his literalized form as alcohol.

The period before World War Two marked the transition to the consumer culture. After the war, the bulk of industrial activity became the manufacture of “goods.” Rather suddenly, as youth became an ideal, advertising suggested that things people bought would make and keep them young. Prior to this time, elders almost everywhere had enjoyed the highest respect, while adolescence had been a brief period of intense preparation for adulthood.

A society that was in some ways diminishing the possibilities of life for millions of young people declared that it was best, like Peter Pan, to never grow up. Maturity implies transcending innocence and confronting memory.

In 1930, former slaves and survivors of the Wounded Knee massacre were still alive. There was much to remember and much to deny. Staying young is a way of “killing time” (the god Kronos). But in doing so, we leave little to the next generation. We trade experience for innocence.

In 1930, former slaves and survivors of the Wounded Knee massacre were still alive. There was much to remember and much to deny. Staying young is a way of “killing time” (the god Kronos). But in doing so, we leave little to the next generation. We trade experience for innocence.

And we fall back upon one-dimensional images of what it means to be a man. After the war, John Wayne modeled a powerful yet restrained and sexually detached masculinity. As a primary figure in the cult of celebrity, Wayne’s stereotyped roles merged with his public persona and his political statements. His image would be overwhelmingly present in the psyches of three generations of American men. Robert Bly once joked that the only images of masculinity available to young men in the 1960s were Wayne and his reverse-image, the “wimpy” Woody Allen.

In many of his films (Sands of Iwo Jima, Red River, The Searchers, She Wore A Yellow Ribbon, The Horse Soldiers), his characters are widowed, unrequited in love, divorced or loners who reject any erotic relationships. They symbolize the man who has failed or never even attempted the initiatory confrontation with the feminine depths of his own soul.

The classic heroes of myth often find beautiful maidens, enact the sacred wedding (hieros gamos) and produce many children. But many heroes of popular culture (with exceptions such as James Bond and comic antiheroes) don’t get or even want the girl. Even Bond remains a bachelor. Often the hero must choose between an attractive sexual partner and duty to his mission. Some (Batman, the Lone Ranger, etc) prefer male “sidekicks.” Hawkeye, the Virginian, Superman, Green Lantern, Spiderman, Rambo, Sam Spade, Indiana Jones, Robert Langdon, John Shaft, Captains Kirk, America and Marvel: all are single. Their sexual purity (or at least their avoidance of committed relationship) seems to ensure their moral infallibility, but it also denies both complexity and the possibility of healing.

This hero has inherited an immensely long process of abstraction, alienation and splitting of the western psyche. He exemplifies, wrote Hillman, “…that peculiar process upon which our civilization rests: dissociation.” He refuses any relationship with the Other, demonizing it into his mirror opposite, the irredeemably evil. He requires no nurturance, doesn’t grow in wisdom, creates nothing, and teaches only violent resolution of disputes, which reinforces our own denial of death. His renunciation justifies his furious vengeance upon those who cannot control their appetites for power or sex. He defends democracy through fascist means. He offers, write Jewett and Lawrence, “vigilantism without lawlessness, sexual repression without resultant perversion, and moral infallibility without… intellect.”

Post-war optimism created a large shadow that Noir films expressed. Men had won the war; shouldn’t they be happy? Wayne’s cowboy movies were allegories with clear social overtones. Tim Riley writes, “It was as if the cold-war curtain came down both across Europe and across some imaginary field in the American male psyche…” To Clarissa Pinkola-Estes, the war created “a culture turned back on itself… one that had become dry from much loss of blood.” In On The Road, Jack Kerouac spoke for many men: “…wishing I were Negro, feeling that the best the white world had offered was not enough ecstasy for me, not enough life, joy, kicks, darkness, music, not enough night.”

Women, millions of whom lost their jobs to the returning soldiers, were also in a bind. Betty Friedan described a deep sense of depression, frustration and resentment. Magazines that had encouraged women to go to work before the war now praised “homemakers,” with “a single purpose… to sell a vast array of new products…”

Here is where we have to take a step or two away from history or even psychology into a more poetic imagination. Both resisting and longing to heal the mind-body split so perfectly represented by John Wayne, America dreamed up a moistening archetypal presence, at least one living soul who might enact the needed mysteries. Years later, John Lennon would sum up the situation: “Before Elvis, there was nothing.”

Part Four

Despite the anxiety of the nuclear age, peacetime unleashed a torrent of energy and domestic production. Large-scale government programs such as the G.I. Bill lifted millions out of poverty and into the suburbs. Yet something was missing. Television hinted at what it might be with its low-key sexualization of commodities. Advertisers discovered that nothing sells so well as when it is subtly associated with the female body, even if it has no individual essence.

Ownership of mass-produced products created a placeless community of consumers.  “Men who never saw or knew one another,” wrote Daniel Boorstin, “were held together by their common use of objects so similar that they could not be distinguished even by their owners.” Never before had so many people determined their identity in such a thin and artificial way.

“Men who never saw or knew one another,” wrote Daniel Boorstin, “were held together by their common use of objects so similar that they could not be distinguished even by their owners.” Never before had so many people determined their identity in such a thin and artificial way.

White children born after the war were the first in history to grow up in such relative affluence, the first to be raised under Dr. Spock’s permissive ideas, the first to expect an extended adolescence in college — and the first to deeply question the values and motives of their parents.

Circumstances were preparing the ground for the emergence of the youth culture. The early 1950s witnessed a convergence of unique factors, starting with the baby boom. From 1947 until 1980, the population of thirteen to thirty-year-olds would increase every year. By 1956, thirteen million teens would be spending $7 billion/year. They had no memory of the Depression or the war. But they were aware that nuclear war might instantly negate everything, and they had no instinct to save money. At a deeper level, however, their bodies were about to explode in the universal, if inchoate, cry for initiation. By 1960, three-quarters of movie audiences would be teenagers, prompting a Hollywood executive to complain, “It’s getting so show business is one big puberty rite.”

Rural America’s population declined steeply. Between 1945 and 1970, 25 million people would leave the farms forever. Advertising and cheap mortgages (for whites) made possible by the G.I. Bill convinced everyone that cars were a necessity. But the new mobility contributed to the breakdown of urban, ethnic communities. In previous migrations, large, multi-generational groups had moved together, following two persistent themes of American myth: cities were no good; and one could always make a new start by settling the wilderness.  Indeed, by the mid-1950s, city life in the popular imagination was encapsulated by Ralph Kramden’s cramped apartment in The Honeymooners TV show. Meanwhile, Father Knows Best, Ozzie And Harriet, etc, presented suburbia as the Promised Land.

Indeed, by the mid-1950s, city life in the popular imagination was encapsulated by Ralph Kramden’s cramped apartment in The Honeymooners TV show. Meanwhile, Father Knows Best, Ozzie And Harriet, etc, presented suburbia as the Promised Land.

Suburban whites attempted to live within cocoons of unexamined privilege, rarely encountering an African- or Mexican-American except as a servant.  This isolation perpetuated racist beliefs and kept white cultural norms invisible. In 1963, two out of three whites would tell pollsters that blacks were treated equally, and ninety percent believed that black children had equal educational opportunity.

This isolation perpetuated racist beliefs and kept white cultural norms invisible. In 1963, two out of three whites would tell pollsters that blacks were treated equally, and ninety percent believed that black children had equal educational opportunity.

But this escape from the inner cities had a different intention and a different result. Countless young couples left the ethnic accents and recipes of their parents behind. They were no longer “hyphenated Americans,” but simply Americans. As this happened, a generation of children grew up missing the experience of living with extended families. They lost connection to elders, who were being exiled to retirement communities or nursing homes. The nuclear family was essentially little more than an isolated consuming unit. And yet the new emphasis on individualism was negated by relentless advertising pressure that channeled most personal choices toward conformism.

“Organization men” gave their allegiance to corporations and uprooted their families from one suburb to another whenever their jobs changed. William Whyte wrote that they “left home spiritually as well as physically, to take the vows of organization life.” IBM executives would joke that the initials of their company stood for “I’ve been moved.”

Something else was disappearing – the oral tradition. Previous generations had learned their myths (and their history, which were often the same thing) by listening repeatedly to storytellers. And as the unmediated, oral transmission of culture was dying out, technology was making it easier for white youths to encounter the cultural creations of the Other. By 1955, three-quarters of households would have TV. Sales of transistor radios would rise from 100,000 units in 1955 to 5,000,000 by the end of 1958. By 1960, American companies would sell ten million portable record players a year.

As for their parents, the images in their heads had been delivered in two main ways: over the radio, into their private living rooms (at least radio allowed them to imagine); or from watching movies, the one experience that most Americans now had in common. Movies, writes Ventura, had “usurped the public’s interest in the arts as a whole and in literature especially”. Whereas indigenous people had participated in their entertainment, Americans (except for dancing) were passive consumers of culture. The Western mind-body split comes to its extreme in the concept of an audience. It “… has no body… all attention, all in its heads, while something on a screen or a stage enacts its body.”

Television added a new dimension; it portrayed events far away as they happened. By showing how others lived, especially the contented middle class, it raised expectations among the poor and had an immediate impact on politics. And it showed teenagers dancing. Ultimately, though, TV turned Americans into “couch potatoes.” When they were not in their cars, enjoying the freedom of the open road, they were generally at home, glued to the tube.

Soon, the tube would be on six to eight hours per day, as millions ritually asked, “What’s on tonight?”  Consuming their junk-food snacks along with the myths of post-war America, they witnessed happy, white, suburban families, with either benevolent patriarchs (Robert Young) or irrelevant but lovable Dads (William Bendix). And they observed, over and over, the righteous hero confronting the Other, who appeared as commie, gangster, redskin or space alien. But all dilemmas, comic or serious, resolved themselves just before the final commercial.

Consuming their junk-food snacks along with the myths of post-war America, they witnessed happy, white, suburban families, with either benevolent patriarchs (Robert Young) or irrelevant but lovable Dads (William Bendix). And they observed, over and over, the righteous hero confronting the Other, who appeared as commie, gangster, redskin or space alien. But all dilemmas, comic or serious, resolved themselves just before the final commercial.

Commercials. Americans came to expect regular interruptions to hear that redemption could be achieved through purchasing the latest products.  The 300-year-old Puritan heritage of delayed gratification was being pushed underground, like the pagan gods themselves, not to re-emerge for thirty years. Even before the end of the war, economist Victor Lebow had pronounced without irony that the economy

The 300-year-old Puritan heritage of delayed gratification was being pushed underground, like the pagan gods themselves, not to re-emerge for thirty years. Even before the end of the war, economist Victor Lebow had pronounced without irony that the economy

…demands that we make consumption a way of life, that we convert the buying and use of goods into rituals…We need things consumed, burned up, replaced, and discarded at an ever-increasing rate.

Having endured a generation of depression and war, adults were claiming their reward. But they also sacrificed something. Instead of ancestors and spirits, they worshipped entertainers, athletes and name brands. Remnants of ancient clan competition still existed, but now it was between Ford and Chevy, Budweiser and Miller or Cheer and Tide. And few asked the old questions anymore: What is my purpose in this life? Whom do I serve? What do I owe to those who came before me and those who come after me?

One could certainly make a case against this last statement. Millions of Americans who had survived depression and war scrimped and saved so their children might have the material advantages they had never had themselves. Yet, when the baby boomers articulated their rebellion, they commonly lamented the commercialized, dangerous, polluted, banal and meaningless world of their parents. The fathers, especially, were simply not present. Psychologist Joseph Pleck notes that Freud and Jung had seen the father as critically important in the child’s psychological development, but now he was “a dominating figure, not by his presence, but by his absence.”

Students of myth may recognize this figure as a modern version of the ancient Greek Ouranos, as I write here:

The Titan Ouranos, first ruler of the universe, heard a prophecy that a son would overthrow him. So he pushed his children back into the body of Mother Earth. One son, Kronos, escaped and then castrated and deposed him. Fearing a similar prophecy, Kronos ate his children. His Roman equivalent Saturn eventually came to personify Father Time, which devours all things…For 4000 years, or 200 generations, Ouranos and Kronos, the original patriarchs, have been our models for two extreme patterns of fathering. Ouranos is the classic absent father: gone, drunk, uninvolved, hidden behind the newspaper, brushing off needy children with, “Ask your mother.” By contrast, Kronos is overly involved: tyrannical, judgmental, abusive. Ouranos neglects the children, but Kronos kills them with his unreasonable and unquestionable expectations.

By the mid-1960s, American youth would intuitively understand that Kronos had overthrown his father and was eating his children. But for now, Dad and his values were simply irrelevant.