I naively thought that I’d covered the entire range of issues related to the subject of cultural appropriation in the first four parts. I dealt with common themes of authenticity, ownership, privilege, gatekeeping (who gets to decide?), reconstruction, permission, appreciation, calling and community. And: complexity. Here, I have few new concepts to introduce, mainly my own further marveling at how bloody complex this whole issue is, and in no particular order.

As I mentioned in Part Four, the Mexicas (Aztecs) had long celebrated their Days of the Dead in August, before the Spaniards required them to conform to the Catholic calendar. For nearly 500 years, Dia de Los Muertos has occurred on November 2nd. But very recently, we are beginning to see Latinos in Southern California “re-appropriating” the holiday and moving it back to August.There is a huge debate about the difference between “Folklore” and “Fakelore,”defined as “inauthentic, manufactured folklore presented as if it were genuinely traditional.” This leads me to a rather stunning discovery about the “Apache Wedding Blessing,” sometimes known as the “Navajo Prayer.” Who hasn’t heard these words read at a wedding:

Now you will feel no rain, for each of you will be shelter for the other.

Now you will feel no cold, for each of you will be warmth to the other.

Now there will be no loneliness, for each of you will be companion to the other.

Now you are two persons, but there is only one life before you.

May beauty surround you both in the journey ahead and through all the years.

May happiness be your companion and your days together be good and long upon the earth.

They are undeniably beautiful, evocative and moving – and, from an indigenous point of view, totally fake.

They are “traditionalesque,” a phrase coined by Rebecca Mead to describe any tradition invented or refurbished more for the purpose of creating a market than for carrying on a culture. The origins of the blessing are not Native American, but from the imagination of Elliot Arnold, author of the 1947 novel Blood Brothers, which later became the 1950 film Broken Arrow.

Since then, the fictional ceremony has appeared in countless wedding planning resources, “presented with the authoritative tone and use of the ahistorical past tense people use when they believe there is no one around to correct them.”

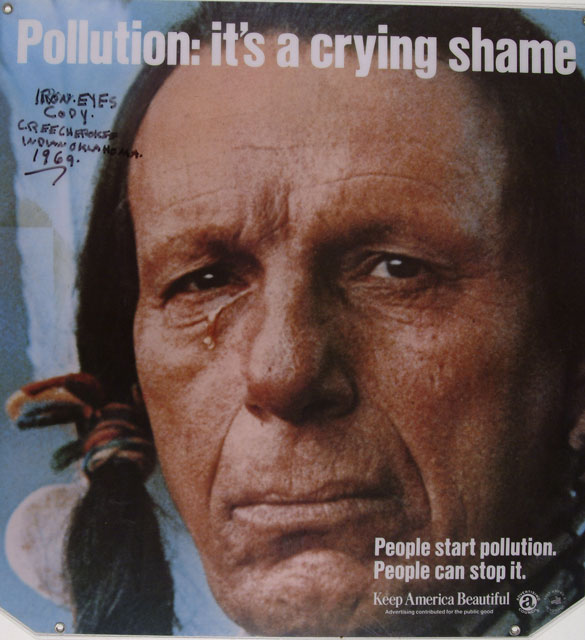

The poem does pass as Native American (as did Espera Oscar de Corti, known as “Iron Eyes Cody,” the Sicilian-American actor who portrayed the famous “crying Indian” in the environmentalist TV commercial). https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/09/iron_eyes.jpg?w=438&h=478 438w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/09/iron_eyes.jpg?w=137&h=150 137w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/09/iron_eyes.jpg?w=274&h=300 274w" sizes="(max-width: 219px) 100vw, 219px" style="background: transparent; border: 0px; margin: 4px 0px 12px 24px; padding: 0px; vertical-align: baseline; display: inline; float: right;" />

https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/09/iron_eyes.jpg?w=438&h=478 438w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/09/iron_eyes.jpg?w=137&h=150 137w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/09/iron_eyes.jpg?w=274&h=300 274w" sizes="(max-width: 219px) 100vw, 219px" style="background: transparent; border: 0px; margin: 4px 0px 12px 24px; padding: 0px; vertical-align: baseline; display: inline; float: right;" />

Is this a reason to stop using it in weddings? Does it make us feel more deeply about the wedding because we think it is Native American? What characteristics do we associate with native people that make us feel this way? Authenticity? Tragedy? Simplicity? Childishness?

And, as usual, it gets complicated. Lia Falk writes

What’s remarkable about this particular invented text is how far from the original it has metastasized, transposing it from fakelore to true folklore: it’s succeeded in masquerading as an authorless text for long enough that individual authors feel permitted to put their own touches on it. Of course, the Internet only speeds up such folk processing. I counted at least seven versions of “Apache Wedding Blessing” besides Arnold’s — it seems that every wedding officiant who’s used it has modified it to make it seem either more ancient and traditional or more palatable to the modern couple.

And as long as we’re talking about weddings, we have to acknowledge another painful aspect of this appropriation business in the Native American community itself. What term should we use to describe the worldwide process in which white Europeans imposed their literalized religious intolerance on the indigenous people they conquered? Cultural impropriation?

Traditional Diné (Navaho) people have always understood gender as a spectrum rather than a binary. Indeed, their language has terms for at least six genders. But after three centuries of contact with Christian fundamentalism, some Diné have absorbed the prejudices that inevitably arise out of literalized, “either/or” thinking. Jolene Yazzie, who has endured homophobia throughout her life, describes a young man named Rei who wanted to undergo a male puberty ceremony but had great difficulty finding a traditional healer willing to accept a transgender man. As for herself,

I identify as “bah” or dilbaa náhleeh (masculine woman)…I prefer a masculine gender role that doesn’t match my sex, but I continue to face bias over my gender expression… In September of 2017, (my partner and I) were determined to have a Navajo wedding and tried to find a traditional healer who would consider a marriage between two women. At one point, I found a medicine woman who supported same-sex marriages, but only if they were performed in a church or other non-Diné venue. She said that according to Navajo tradition, we couldn’t be blessed in the same way as a man and a woman, and she declined to perform the ceremony.

Eventually they found an in-law who held the ceremony, “But for people like Rei Yazzie, such a blessing may still be a long way off.”

These issues are not restricted to whites. Back to the folklore/fakelore conversation, we discover that it isn’t limited to Native Americans. Some argue that the ancient Hawaiian spiritual tradition – Ho’oponopono – was actually invented by a white man in 1935.

Now I’ll offer further complexity, and for a specific reason. When it comes to issues of spiritual belief and practice, we modern people, despite our claims to being comfortable with nuance, are actually obsessed with reducing complex issues to the sound bites of simplicity and literalization.

After completing the first four essays I came across a fascinating book: Talking About the Elephant: An Anthology of Neopagan Perspectives on Cultural Appropriation. The elephant, presumably, is the “elephant in the room” that no one will talk about. The editor brings together a dozen practitioners of various Neopagan paths to confront this issue and reveals some truly esoteric yet quite relevant debates within their communities.

One theme they all agree on is the inauthenticity of the large number of “Native American Tarot decks,”

which should remind us of the common projection of the “Noble Savage,” that “brave and self-sacrificing fellow” who originated not in the wilds of North America but in the imagination of French Romantic authors and colonialists. Kenaz Filan writes that the image

…combined the best of both worlds: they retained the innate decency of their primitive ancestors, combined with the best and most benevolent ideals of Christianity. They provided invaluable assistance to the colonists, and were content with their humble station. They were used to protest the expansionist social order, but also to reaffirm it.

There is a deep and justified anger here, and as I implied in earlier posts, it extends well into the area of modern appropriation. Several Native American websites warn (again, we ask, who decides?) against fraudulent teaching of their traditions – by both Indians and non-Indians:

http://www.thepeoplespaths.net/articles/warlakot.htm

http://www.oocities.org/ourredearth/

http://www.hanksville.org/sand/intellect/newage.html

Indeed, the accusations and lists of frauds and “plastic shamans” are so long they remind us of those endless medieval lists of saints and devils. It all may boil down to the argument that true native people would never charge money for spiritual teachings, nor would they ever say that the teachings of a lifetime can be learned in a weekend seminar (And yet, how does one survive in America without an income? It’s complicated).

This position boils down even further, to a decidedly non-native way of thinking: the Anglo emphasis on purity and sin. Complicated: for every accusation there seems to be a denial.

Caveat: I am in no way criticizing the Native American contributors to these websites, only pondering some broader temptations that white Americans often fall prey to, which I will address in Part Six. As always, I’m more interested in how myth determines motivation and action – and also in the old American tradition of con-men masking as religious leaders.

Meanwhile, the book brings up other issues. Neopagan reconstructionists, for example, struggle with the question of whether it’s even possible to appropriate ancient cultural forms that no longer exist (hint: some of them do think so). Some writers claim that even some Native American and indigenous Siberian (the only group, strictly speaking, who are entitled to use the word “Shaman”) people are consciously reconstructing their own traditions after the devastations of Christianity, capitalism and communism.

Many practitioners of Asatru, the reconstructed, “heathen” worship of the old gods of pre-Christian northern Europe, adamantly claim that admittance into their religion should be strictly limited to those with genealogical proof of Nordic or Teutonic “blood.” Similar groups have adopted Odinist phrases like “Faith, Family, and Folk.”

This is not the first time that those who would revive a Teutonic, Pagan imagination have flirted with authoritarianism. It happened in early 20th-century Germany. More recently, some have taken their obsession with purity to the illogical extreme of white supremacism, appropriating old Norse symbols such as Thor’s hammer as they marched through Charlottesville in the “Unite the Right” rally of 2017, attacked the Capitol in 2021 and participated in many other violent actions.

Most recently, the mainstream of the Republican Party has unapologetically welcomed the most extreme of the extreme, symbolized by the “Othala Rune,” with its unmistakable connection to German Nazism.

This is America in all its glorious contradictions: on the one hand, people making lots of money from the latest flirtation with spirituality and on the other, accusations of fraud and charlatanism. After the Native Americans, the “Celticists” seem to be making the most noise, and perhaps rightly so. Phillip Berhnadt-House, who is both a pagan and a Celtic academic, gives as an example a person who gives workshops on “Druidry and Celtic Shamanism” and who calls himself an “ollamah” (note the spelling); then he notes the actual qualifications that such people needed to attain in ancient Ireland:

An ollamh is supposed to be the son of a poet for three generations, undergoing a period of scholarly training and practice for many years, knowing 350 compositions at the pinnacle of ascent through the seven grades of poet.

And how about Wiccans and the well-known “Celtic Wheel of the Year,” the system of major holidays (sabbats) falling on the solstices, equinoxes and the four calendar dates exactly in between them? For example, Samhain/Halloween is halfway between the autumn equinox and winter solstice.

Thea Faye writes that they celebrate a pattern of the annual “death and rebirth of the God in conjunction with the fertility and life cycle of the Goddess.”

Most practitioners now seem to have accepted the scholarly consensus that the tradition was more or less invented around 1940 by Gerald Gardner, who gave a strongly British cultural accent to it. So much so, in fact, that some argue that there is little historical evidence of connection to the broader Celtic heritage of continental Europe.

All well and good; but the Wheel and its holidays, as Gardner reconstructed them, are all very specifically shaped by the natural, historical and mythic worlds of the British Isles, at their northern latitude. So, asks Faye, what happens when Wiccans in the southern hemisphere want to celebrate the Wheel? Shouldn’t they simply “spin the Wheel on its head” and reverse the order of the sabbats? Why not observe Samhain, the Celtic New Year, on April 30th/May 1st? She doesn’t think so: “…stating that the veil is thin on a particular date when it clearly is not is a road to nowhere.” Instead, she recommends knowing – really knowing – the world you live in: “…the beauty of a Nature based spirituality is that it is possible to adapt it to whatever your local environment has to offer.”

Part Six of this essay is here.