So, have Maya and I been engaging in cultural appropriation all these years? And which cultural forms are we making use of? The terms we need to make peace with are calling, permission, authenticity and community.

After participating in several Dagara (West African) grief rituals led by Malidoma Some´at men’s conferences in the 1990s, it was quite clear to me that I was called to this important work. Maya speaks of her calling here.

By the way, even then, Malidoma was incorporating elements of grief work from other cultures that some of us were suggesting! Permission? Malidoma specifically blessed us and told us to take the work into our communities.

Next comes the question of authenticity, the issue over which our friend was challenging us. Like us, she’d been to Mexico, and clearly, to call our event a “Day of the Dead Ritual” was not entirely accurate. To respond, we have to speak of the fourth term, community.

Malidoma, whose elders had sent him to the West, and whose name means “”He who makes friends with the strangers,” taught us, no community without ritual and no ritual without community. In America who among us really has community – people who actually live near each other – willing to engage in these rituals? It’s a conundrum that, if followed literally, is a recipe for fumbling and indecisiveness. As Kenn Day writes in Part Three of this blog, tribal rituals are for healing the entire group. And although traditional Dagara grief rituals require the participation of the entire community and take three full days to complete, Malidoma was clear that neither of those factors should inhibit our attempts to offer the work to the public. It was simply too important to split hairs over.

In that context, Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) in Mexico also lasts for several days. And it is intimately associated with (Mexican) Catholicism. The dead visit their old homes, but the living spend the central night of the festival at their grave sites on consecrated ground. And it is a festival! The grieving is fundamental but not at all the sole emotion, as the people also party with their dead as only Mexicans can. Certainly there is no way to make a relatively short (one-day) event in a public hall for a group of non-Catholics, most of whom have never met each other, into a truly authentic Dia de los Muertos.

So first of all, we remember Michael Meade’s insight: To be honest, we never have real community in the old meaning of the term. The best we can do in this demythologized world is to invite like-minded people of deep intention to come together in brief periods of what he calls “ sudden community.” At our rituals, we encourage everyone to act (and speak) as if – as if we all really were members of a tribe who’d known each other all our lives. We make community for a few hours.

Many indigenous cultures knew the importance of setting aside a period during the year for inviting the dead to return, with terminology that translated as their own Days of the Dead. And they understood that certain liminal times were most appropriate. Cultures that use lunar calendars had (and in the far East, still have) these rituals a half year from the Lunar New Year (first full moon after the winter solstice): often on the first full moon in August. This is what the Mexicas (as the Aztecs called themselves) did. Their holiday lasted for twenty days, beginning on approximately August 8th with Micailhuitontli (Small Feast of the Dead), to honor their deceased children, and ending with Huey Micailhuitl (Great Feast of the Dead), in which they honored those who died as adults.

Again, this appropriation business gets really complicated. Once the padres finally realized that they couldn’t extinguish the ancient rites, scandalous as they were, they forced the Mexicas to change the date of their festival from August to early November, the time of the Catholic festivals of All Saint’s Day and All Soul’s Day. But these festivals in turn had been created in the 10th and 11th centuries, when the (Roman Catholic) Church finally decided that it couldn’t wipe out the immensely old Celtic (primarily Irish) days of the dead.

Samhaim, the Celtic term, had always fallen on that liminal point in the solar calendar precisely between equinox and solstice. This was the day when the light half of the year switched to the dark half of the year and the veil between the worlds was the thinnest, when the boundaries between the seen and unseen worlds became permeable, and the spirits of the dead walked briefly among the living to eat the foods they loved when they were alive. To contemporary Neo-Pagans these are still times for loving remembrance. They are also sacred times, when great things are possible.

And they are dangerous times, since some spirits are hungry for more than physical food. Indigenous cultures from Bali to Guatemala agree that there is a reciprocal relationship between the worlds. What is damaged in one world can be repaired by the beings in the other. Such cultures affirm that many of our problems actually arise because we have not allowed the spirits of the dead to move completely to their final homes by not grieving them fully.

Maya and I had also been attending Spiral Dance, San Francisco’s “Witch’s New Year,” at this time of year, because the Neo-Pagan calendar celebrations seemed to embody our sense that it was critical to attend to these times of transition.

https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/rauner_spiral2012-059.jpg?w=150&h=100 150w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/rauner_spiral2012-059.jpg?w=300&h=200 300w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/rauner_spiral2012-059.jpg?w=768&h=512 768w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/rauner_spiral2012-059.jpg 800w" sizes="(max-width: 552px) 100vw, 552px" />

https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/rauner_spiral2012-059.jpg?w=150&h=100 150w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/rauner_spiral2012-059.jpg?w=300&h=200 300w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/rauner_spiral2012-059.jpg?w=768&h=512 768w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/rauner_spiral2012-059.jpg 800w" sizes="(max-width: 552px) 100vw, 552px" />Spiral Dance

Spiral Dance, now in its 31st year, is both a grief ritual that attends to the dead who briefly return to this side of the veil and a party that welcomes in both the darkness itself and the imagination necessary to move forward.

We’d also been marching in the Day of the Dead Procession.  Latinos in the Mission District had introduced this tradition back in the 1970s, but it soon grew into one of San Francisco’s major events, with thousands of participants, mostly young white artists and college students.

Latinos in the Mission District had introduced this tradition back in the 1970s, but it soon grew into one of San Francisco’s major events, with thousands of participants, mostly young white artists and college students.

Talk about cultural appropriation/appreciation! Critics (who may not have ever been to Mexico) see it as another excuse for a public party before the rainy season drives everyone indoors, with its drumming, samba dancers and political slogans. But each year the procession passes many front-porch shrines and then concludes at a park where people have lovingly created dozens of illuminated shrines to their dead, and the mood shifts from party to profound mourning.

At each shrine, its creators seem to be saying, “Look, I have sustained a deep loss. I must speak of it. I need you to see me. Come weep with me.” Appropriation? I don’t think so.

On the other hand, they do things differently down in Los Angeles (established by the Spanish as El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles, and previously known to the native Chumash as Yaanga, or “Poison Oak Place.”) For twenty years the Hollywood Forever Cemetery has hosted a massive Dia De Los Muertos celebration, with dozens of beautiful and thoughtful ofrendas. All well and good. But this is L.A., where everything invites commercialization. In 2017 Netflix built not one but five of these shrines to honor fictional characters who’d died that year. Appropriation? I think so.

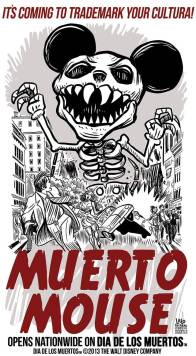

It gets crazier. In 2013, the Disney Corporation attempted to trademark the phrases “Día de los Muertos” and “Day of the Dead”. The Latino community responded with a petition featuring a ferocious poster advertising “Muerto Mouse” and quickly gathered over 20,000 signatures.  Disney, to its credit, backed down and even hired the poster’s creator Lalo Alcaraz as a creative consultant on the film Coco, which with his help turned out to be culturally accurate.

Disney, to its credit, backed down and even hired the poster’s creator Lalo Alcaraz as a creative consultant on the film Coco, which with his help turned out to be culturally accurate.

Anyway, Maya and I couldn’t help but notice that Celtic New Year and Day of the Dead had far more in common than differences, and that both were completely consistent with the Dagara ritual imagination. How, I asked Malidoma, do people acknowledge seasonal transitions in an equatorial country such as his (Burkina Faso), where there is no difference between the light and dark halves of the year? He answered that the Dagara take note of daily transitional times, dawn and dusk, which are also fraught with significance.

We had also been learning some of Martín Prechtel’s teachings from Guatemala, where the ancestors require two basic things from us: beauty and our tears. The fullness of our grief, expressed in colorful, poetic, communal celebrations, feeds the dead when they visit, so that when they return to the other world they can be of help to us who remain in this one. And by feeding them with our grief, we may drop some of the emotional load we all carry simply by living in these times. The ancestors can aid the living.

But they need our help to complete their transitions. Without enough people weeping for it on this side, say the Tzutujil Maya, a soul is forced to turn back. Taking up residence in the body of a youth, it may ruin his life through violence and alcoholism, until the community completes the appropriate rites. This is the essential teaching: when we starve the spirits by not dying to our false selves and embodying our authentic selves, the spirits take literal death as a substitute.

Here was yet another indigenous custom that seemed completely consistent with what we were doing. By the time we were able to travel to Bali and witness a traditional village cremation ritual, we were hardly surprised to see the cross-cultural parallels.

https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/balinesehindusholdmasscremation2zfke1qzcwwl.jpg?w=150&h=100 150w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/balinesehindusholdmasscremation2zfke1qzcwwl.jpg?w=300&h=200 300w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/balinesehindusholdmasscremation2zfke1qzcwwl.jpg 594w" sizes="(max-width: 521px) 100vw, 521px" />

https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/balinesehindusholdmasscremation2zfke1qzcwwl.jpg?w=150&h=100 150w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/balinesehindusholdmasscremation2zfke1qzcwwl.jpg?w=300&h=200 300w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/balinesehindusholdmasscremation2zfke1qzcwwl.jpg 594w" sizes="(max-width: 521px) 100vw, 521px" />Balinese cremation ritual

It made perfect sense to us to respectfully incorporate them all into our rituals.

We recall Lupa Greenwolf’s words from Part Three:

So I very carefully reviewed what my practice entailed, did my best to claim that which I created myself while also being honest about how other cultures’ practices inspired me, and that’s where I drew my line, where I would back up no farther.

This is a good time to mention that David Chethlahe Palladin had an authoritative opinion on this issue. He was a legitimate shaman and one of the best-known Native American artists of his generation (read about his extraordinary life story here). As a painter, he mixed images from world mythology with traditional Navaho themes and wrote:

There may be times in our personal evolution when we become aware of archetypal themes that exist within the universal consciousness, and we draw upon them, regardless of their cultural or tribal origin.

Pagan thinking appreciates diversity and encourages us to imagine. Myth is truth precisely because it refuses to reduce reality to one single perspective. We came to entertain the possibility that if there is such a thing as truth, it resides in many places. And we felt called to appreciate the wisdom from many indigenous cultures, rather than to follow one path exclusively.

Besides, we felt that the times are too painful and the need too strong to reject anything authentic. We have proceeded on the basic assumption that we need all the help we can get. Even Malidoma used to begin his invocations with a prayer to the ancestors acknowledging that so much wisdom had already been lost, that he was clumsily trying his best and hoping that the spirits would reciprocate.

Curiously, we also came to realize that whenever we encounter people of serious intention who are also attempting to revive a truly indigenous imagination on American soil, they seem to intuitively understand the basic principles of ritual. Radical ritual, that is:

1 – We all carry immense loads of unexpressed grief. This is unfinished business and it keeps us from being present or from focusing on future goals.

2 – Beings on the other side of the veil call to us continually, but it is our responsibility to approach them through ritual, and this often implies creating beautiful shrines that visually represent that other side.

3 – Radical ritual implies creating a strong container, clarifying intentions, inviting the spirits to enter and not predicting the outcome. Radical ritual is by nature unpredictable. It is not liturgical but emotional.

4 – Radical ritual is always communal work.

5 – The purpose of radical ritual is always to restore balance.

6 – We must move the emotions. When ritual involves the body, the soul (and the ancestors) take notice. We dance our grief. Spontaneous, strong feeling indicates the presence of spirit.

7 – Ritual involves sacrifice. We attempt to release whatever holds us back, sabotages our relationships or keeps us stuck in unproductive patterns. In this imagination, the ancestors are eager for signs of our commitment and sincerity. What appears toxic to us, that which we wish to sacrifice becomes food to them, and they gladly feast upon both our tears and our beauty.

When we meet people with similar interests from other parts of the country, either we find that they have already intuited the same basic principles or are quite willing to learn them.

And – when we hear about what some other ritual teachers are offering, we can’t fail to notice the expensive rates they charge. Are we – who never refuse admission to our grief rituals to anyone for lack of funds – to judge them for their avaricious practices? Well, this is America after all, and perhaps such people are making a curious gesture of veneration for their Protestant ancestors! Perhaps Americans simply don’t value things if they don’t cost a lot. Indeed, as a ceramicist tells us, “When my pots don’t sell, I simply raise the price.”

Moral inventory or self-justification?

In summary, after researching this appropriation/appreciation dispute, we feel that our work and our terminology – a Day of the Dead Grief Ritual – fall squarely on the side of deep appreciation, with emphasis on calling, permission, authenticity and community. May the ancestors hear our cry and bless our endeavors. What do you think?