Part Four – 1999 to the Present

The man who crawled under a hail of bullets in 1992 to save the Sarajevo Haggadah is profoundly sad. He says Bosnian culture survived the war, but he’s not sure it can survive the peace. Enver Imamovic doesn’t know what the fate of the Haggadah will be, and he knows that the government doesn’t care.

The 1995 peace agreement that ended the Bosnian war split the nation along ethnic lines into two semi-autonomous parts linked by a weak central government and guided by a constitution that left Sarajevo’s cultural institutions no guardian and little funding.

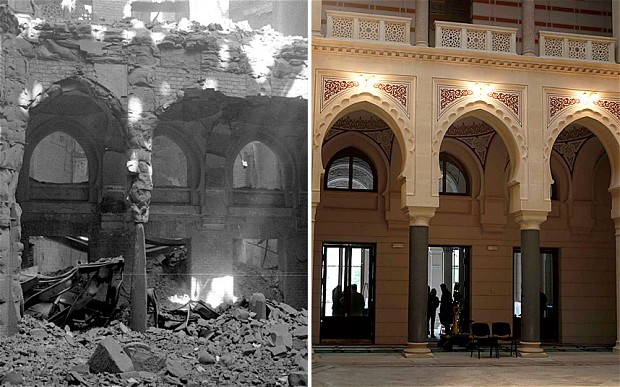

Still, the Bosniaks of Sarajevo managed to rebuild their National Museum, which the Serbs had tried so hard to erase from memory, and the Haggadah went on display in 2002. The imagination of another time when diversity was respected survived because some people in our time could still appreciate – and celebrate – difference.

The Siege of Sarajevo was the longest siege of a capital city in the history of modern warfare, lasting nearly four years, more than a year longer than the siege of Leningrad. Twelve thousand died, including nearly 600 children. But culture had been “a form of resistance,” says an art history professor. “Women were wearing high heels and running from snipers to get to openings.” Another woman, a long time employee of the museum (whose director was killed in the bombardment) adds that despite it all, “we even put on two exhibits during the siege.”

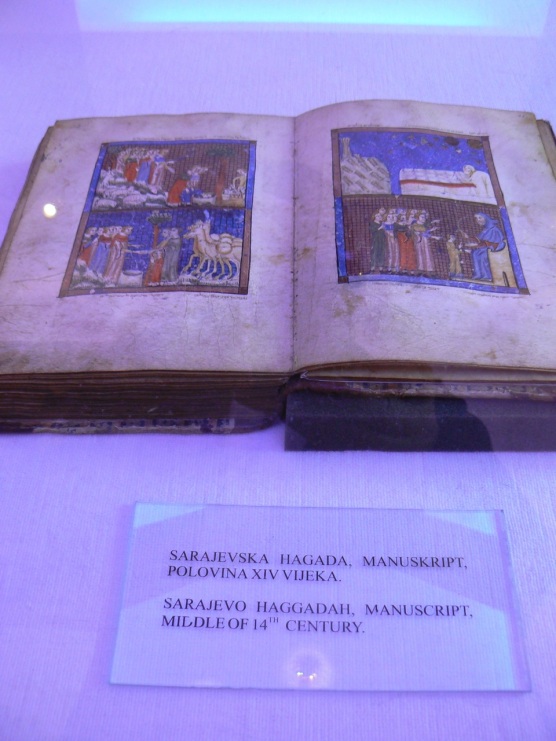

In the rebuilding stage, the Museum equipped a special vault with a bulletproof glass door to protect its most valuable artifact. Only with special permission could one enter, and no one but a curator could touch this richly decorated medieval manuscript. Several copies were made of the Haggadah and the original 660-year-old manuscript, symbol of such a unique legacy, was insured for 700 million dollars. The literary world became aware of it in 2008 when Geraldine Brooks’ novel People of the Book became a bestseller.

But post-war Sarajevo is a very different place. The peace agreement that was supposed to help the country heal enshrined its ethnic differences in a constitution and created a hydra-headed government that allows (perhaps even forces) people to cleave to their bloodline. Only institutions that speak to each group’s national identity receive any financial support. There was no agreement on funding for the upkeep of a multicultural legacy. For years, the museum survived on grants and donations until those funds dried up.

In 2011 the Muslim Grand Mufti of Bosnia and Herzegovina presented a copy of the Haggadah to a representative of the Chief Rabbinate of Israel as a symbol of interfaith cooperation and respect.

But in 2012, the Museum shuttered its doors after going bankrupt and not paying its employees for almost a year, leaving future exhibition of the Haggadah in limbo. Two years later, many employees were still working without pay to maintain the collection and the library, which still holds some 162,000 volumes.

In 2013, the year that Servet Korkut died at age 88, the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art attempted to arrange for a loan of the Haggadah, but because of ongoing internal political battles, Bosnia’s National Monuments Preservation Commission eventually refused the loan.

Unresolved ethnic hatred still bubbles below the surface of the Balkan states, and that situation is mirrored in Israel, where, nearly seventy years after the creation of the state and 500 years after they were forced out of Spain, many Sephardic Jews still claim that the dominant Ashkenazi (from Eastern Europe) group still treats them as second-class citizens. As in America, racial/ethnic identity still trumps human compassion and solidarity. Everywhere, as Yeats wrote a hundred years ago, “The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.”

But the descendants of the two families whose fates have been so intertwined have prospered. And, while the Haggadah is safe if unavailable for viewing, you can see its pages online here.

The little book has lived through a story where myth and history come together, a story (like all the great stories) that has no happy ending, indeed has no ending at all but simply invites us into an imagination of where it might go from here. Has it arrived at an impasse, or it is merely taking a breather?