PART TWO: 1942 to 1992

To be born is to be weighed down with strange gifts of the soul, with enigmas and an inextinguishable sense of exile. – Ben Okri

Sarajevo was a rich cultural ferment that included Muslims, Catholics, orthodox Christians and Jews. People often called it “Little Jerusalem.”

Most students of history know that the city played a small but significant role in 1914, when the assassination of a Serbian noble set off the mad chain of events that led to the start of the Great War. But here we are interested in Sarajevo’s role in World War Two. In 1942 the city was absorbed into the puppet state of Croatia, its tolerant, cosmopolitan culture crushed by the invading German Army and the Croatian Catholic, Fascist Ustashe, who were determined that their new state would be cleansed of Serbs (who, as Eastern Orthodox Christians tended to side with Russia), Muslims and Jews.

Now some actual, historical names enter our story, and some are still alive today.

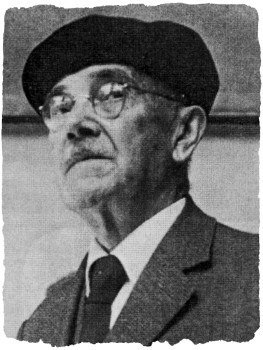

As the Third Reich rounded up Europe’s Jews for extermination, Hitler gave instructions to find and secure Jewish cultural artifacts for a museum he was planning. In April, the notoriously cruel Nazi commander, General Fortner, arrived at the Sarajevo museum with a demand. The director, who spoke no German, asked his chief librarian, Dervis Korkut, to act as a translator. A few minutes before the meeting, Korkut – a Muslim – pleaded to be allowed to take the Haggadah and keep it out of Nazi hands. The reluctant director warned, “You will be risking your life,” but he agreed.

Dervis Korkut

The two men hurried to the basement and removed the Haggadah from its safe. Korkut tucked the small codex, which measured about six by nine inches, into the waistband of his trousers. Then they made their way back upstairs to face the general, who had come specifically for the Haggadah. But the director lied and claimed that he had already given it to one of Fortner’s officers. Frustrated, Fortner left.

That afternoon, Korkut drove out of the city, to a remote mountain village on Bjelasnica mountain, where his friend was imam of the local mosque. There, for the duration of the war, this man hid the Haggadah among Korans and other Islamic texts. In another version of the story, they hid it under the floorboards of a shepherd’s hut. Years later, again with the help of Muslims, it returned to the museum.

But what really matters in the Korkut family is another rescue—of a young Jewish woman. “In our family,” his daughter Munib says, “the Haggadah is a detail. What my father did for Jewish people—that is the biggest thing that we, in our family, have to be proud of.”

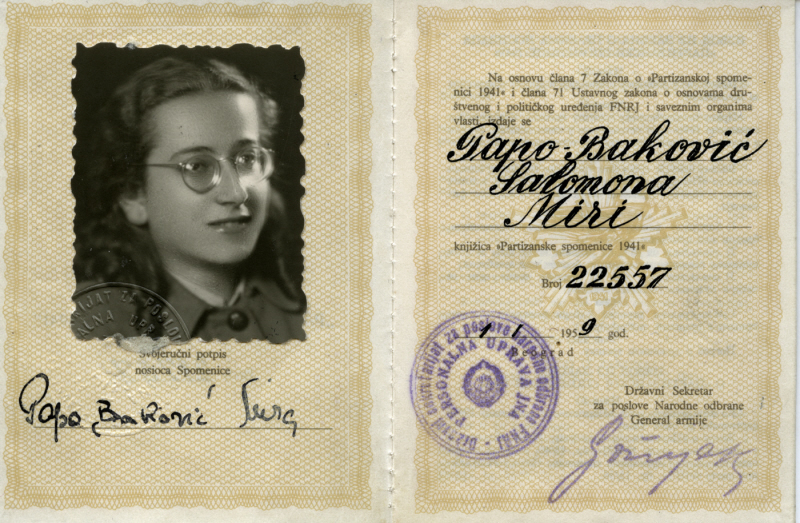

The girl, Mira Papo, like most Sarajevo Jews, was descended from Ladino- speaking Sephardic exiles who, over the centuries had made the same journey as the Haggadah. After seeing her family deported to the death camps, she escaped and joined the Communist partisan Resistance, changing her name from her birth name of Donna to Mira. Throughout the brutal winter of 1942, Mira served in the mountains harassing the Germans, who, led by the same General Fortner, were perpetrating widespread massacres and burnings of villages.

Jewish Yugoslav partisans

Exhausted, with death squads searching the winter forests for stragglers, she returned to Sarajevo. No one she had known was left and her family’s house was boarded up. With nowhere else to go, she went to the park and fell asleep on a bench. Early in the morning, a passerby recognized her and promised to find help. He asked Dervis, who had recently saved the Haggadah, to take her in.

Despite not knowing her and despite the considerable risk – he was a prominent person and German officers frequently attended concerts in his home – he and his wife Servet took Mira in. Servet gave her one of her own traditional Muslim veils—a zar—that conceals the body and most of the face like a chador, and the Korkuts passed her off as a Muslim servant who was caring for their infant son. Mira and Servet became best friends. After four months, Mira obtained false identity papers and escaped to safety.

Mira Papo

The Nazis killed 80 percent of Sarajevo’s 12,000 Jews and destroyed its eight synagogues. In 1944 they rounded up, deported and gassed the Jews in the aforementioned Ghetto of Venice, as well as almost all of Thesalonika’s 50,000 Jews (almost all of them Ladino-speaking Sephardim).

Curiously, only one German-occupied country refused to give up its Jews – Muslim Albania, and it has its own remarkable heroes, such as Ali Sheqer Pashkaj. “Why did my father save a stranger at the risk of his life and the entire village?” asked his son, “My father was a devout Muslim. He believed that to save one life is to enter paradise.”

After the war, Mira returned to Sarajevo, became an army officer and married another former partisan. In 1946, Servet found her and begged help for her husband. The new Yugoslav regime was taking vengeance against the Nazis and the Ustashe and executing many, including General Kortner. But they were also using these war-crimes trials to silence dissident voices. Dervis Korkut, just as unwilling to bow to Communist excesses as he had to Fascism, had become an outspoken critic of Yugoslavia’s oppressive attitudes toward religion. Now, they were accusing him of being a Nazi collaborator.

Mira assured Servet that she would testify on his behalf, but she did not come to court. Her fiancé feared that the Party would turn its wrath upon them if she appeared as a witness for someone in what was clearly a politically motivated trial. He refused to let her leave their apartment and give evidence for Dervis, the man who had saved her life.

In 1948, Mira’s son Davor was born. Mira lived as a devoted Communist but was haunted by guilt for the rest of her life. Over time, she became disillusioned with the dream of a socialist utopia and began to reconnect with her Jewish roots. Davor immigrated to Israel in 1970 and she followed two years later.

Meanwhile, the regime didn’t execute Dervis. Other people came forward who knew about the Haggadah and did testify on his behalf. But he still received a stiff prison sentence. He served six years, mostly in solitary confinement, while Servet and their son were temporarily homeless. After his release he resumed his old job, but he never received his passport and he lost citizenship rights. In 1955, a daughter, Lamija, was born. Dervis died in 1969.

Time passed and Europe let go of its wounds, or thought so. In reality, the old enmities, like the Titans of Greek myth, had merely been cast into the underworld of unresolved forgetfulness, where they festered and grew in strength. In 1984, modern Sarajevo hosted the Winter Olympics and once again proudly showed off its cosmopolitan, tolerant self to the world. Soon, however, the Bosnian War erupted, shattered that image and eventually claimed another 250,000 dead.

Only eight years after the Olympics, on May 17th 1992, Serbian artillery destroyed Sarajevo’s Oriental Institute. In less than two hours, 10,000 books and 5,000 unique Turkish, Persian and Arabic manuscripts were lost in flame.

Then, on August 27th (almost precisely 500 years from the date the Jews left Spain, and fifty years after Dervis had saved the Haggadah), the Serbs began to shell the National Library and Museum. In support of the attack, they dropped dozens of shells on adjacent streets, deliberately preventing the fire brigade from coming into action.

The attack lasted less than half an hour, but the fire lasted into the next day. The sun was obscured by the smoke of books, and all over the city sheets of burned paper, fragile pages of grey ash, floated down like a dirty black snow. Catching a page, said local people, you could feel its heat, and for a moment read a fragment of text in a strange kind of black and grey negative, until, as the heat dissipated, the page melted to dust in your hand.

Bosnian National Library

During WW II the Nazis had burned twenty million books, but not in one place (rather, in about 45 different places). This single day in Sarajevo, then, may have been the biggest book burning in history – over a million books.

And yet, under sniper fire, the citizens of Sarajevo formed a human chain to pass books from the flames.

Why, like 16th-century Catholics and 20th-century Nazis, did the Serbs want to burn books? The answer is that cultural productions are the places of memory, the kindred fruits of the human imagination. They tell stories of complexity and nuance, the very things ideological purists hate the most. Burning books creates the situation where the people of a society (in this case, Muslims who had lived in Sarajevo for 500 years) might have no memory of their past. So don’t the surviving artifacts symbolize both tolerance and resistance?

And the Haggadah? It was saved once again by an archaeology professor, another Muslim.

Enver Imamovic convinced several policemen to drive him through a rain of bullets and mortar shells in order to get to the burning museum. When the chief of police asked him incredulously whether the book was as valuable as a human life, Imamovic, without hesitating, said yes.

He and the policemen spent many hours searching the cavernous structure before they found and broke into the fortified safe that held the Haggadah. Then they braved the bullets once again to get it to the city’s central bank vault and locked it up for the rest of the war.

Enver Imamovic

In an interview, Imamovic remarks that it’s only foreign reporters who ask why Muslims would risk their lives for a Jewish book. The fact that all the men involved in the rescue operation were Muslims actually reveals the most important quality of prewar Sarajevo.

Although Serb nationalists attempted to separate ethnic identities, most Bosnians — especially those in Sarajevo — didn’t see themselves as Muslims, Croats and Serbs: they were all part of a shared identity. Imamovic says the city’s Jewish heritage was as important to them as any other because it’s what made Bosnia the rich cultural mix that the nationalists wanted to destroy. The Haggadah was a symbol of that.

But this story is not over.