Readers of this blog may recall that one of the basic themes of the myth of American Innocence is what I have called the Paranoid Imagination. Previous essays on this subject include The Paranoid Imagination, Porn (Parts one and Two) and Sacrilicious! (Parts One and Two). Here, I’d like to review some of those thoughts and then show one of the ways the paranoid imagination expresses itself in our current political madness.

The paranoid imagination is rooted in the constant anxiety that our Puritan ancestors experienced. It combines eternal vigilance, creative sadism, contempt for the erotic, obsessive voyeurism and an impenetrable wall of innocence.

Its practitioners put a fundamental – and fundamentalist – stamp on American consciousness: human nature was utterly corrupt, and the only escape was through grace. The Calvinist doctrine of predestination declared that from the beginning all persons had been either condemned or saved. Their anxiety arose, however, from the fact that no one could ever be certain of their salvation. They were at war with the self yet unable to escape it. Their only respite from the weight of original sin was to project their guilt onto others. Since they defined loss of self-control as the basis for all sins, their answer to the perceived disorder in the world was unrelenting discipline. Christianity’s hatred of the body (and the rage it engendered) reached its extreme in Puritanism. They loathed sensuality and mistrusted (and – this is crucial – envied) those who didn’t “crucify their lusts.”

Propriety and cleanliness were external indications of a clean soul, and bodily needs continually reminded them of their original, corrupt nature. Since they experienced constant fear – and fantasies – of pollution, they rigidly enforced moral standards. Calvinism’s “most urgent task,” wrote sociologist Max Weber, was “the destruction of spontaneous, impulsive enjoyment.”

And they displayed another aspect of the Paranoid Imagination: the fear and hatred of images. New England Puritanism (and most of America’s intellectuals and writers for several generations were Puritans) attempted to regulate the internal fantasies of all members of the community. But the more images are controlled, the more we are obsessed with them and the more they demand recognition (“to think about again”).

So it should be no surprise that one of the shadow aspects of puritanism has always been the obsession with those same images. The paranoid imagination seeks itself: it constantly projects its fantasies outward onto the Other and then proceeds to demonize it. It is not simply desire, but detailed images of desire, that they project upon the Other.

Another source of their anxiety: Just as American Protestants were condemning the body and its lusts, they were also embodying the most radical form of individualism the world has ever seen. Even as they demonized those “Others” (red natives and black slaves) upon whom they had projected the inability to control themselves, they were working out the details of a mythology that still speaks of unlimited, capitalistic opportunity and personal freedom, including the freedom to ignore centralized authority and all restrictions on personal behavior.

This is crazy-making. Americans value freedom of choice above all, and often hate people who make (or appear to make) personal lifestyle choices that they disapprove of. Consider, for example, those who despise big government’s potential to restrain their business opportunities, yet would use its power to take abortion rights away from women.

In time, capitalism’s relentless logic eventually transformed a religious, if flawed, impulse into the drive for conspicuous consumption. Over three centuries, Americans gradually shifted from being primarily producers to being primarily consumers. They began by enshrining gain without pleasure and ended with addiction to “stuff.”

But this transition evoked tremendous guilt, so the con men of advertising were there every step of the way to assist the process. And they knew the power of images, especially the power of the return of the repressed.

Long before, wrote Phillip Slater, civilization had invented artificial scarcity by restricting the availability of something that theoretically isn’t scarce – sexual gratification. Although most societies do this to some extent, capitalism takes it much further. Advertising attaches sexual interest to inaccessible, nonexistent or irrelevant objects and motivates people to work endlessly for rewards that may never come. Throughout the 20th century, the American genius of marketing has been to associate images of the unattainable female body with consumer products. Crazy-making. Slater, however, writes,

…there is no way to gratify a desire with a symbol… an emotional long shot that will never pay off. They will work their lives away to achieve a love that is unattainable.

Therapeutic Coercion

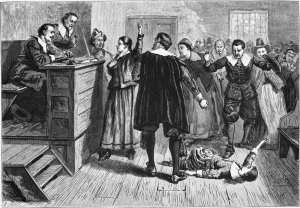

For centuries, the Inquisition – Catholicism’s ritual of purification – had produced a constant state of fear across Europe. A Protestant version took strong root in America, and it periodically re-surfaces in epidemics of scapegoating. Inquisitions are characterized by highly imaginative cruelty perpetrated for the good of the accused. As Blaise Pascal wrote, “Men never do evil so fully and cheerfully as when we do it out of conscience.” This idea of “therapeutic coercion” can be traced back to St. Augustine, who wrote of “forcibly returning the heretics to the real banquet of the Lord.” More recently, American officers in Viet Nam claimed that they had to “destroy the village in order to save it.”

So another aspect of the paranoid imagination, celebrated repeatedly in the Old Testament, is the idea of genocidal yet redemptive violence: “The righteous will be glad when they are avenged, when they bathe their feet in the blood of the wicked.”

Note the complex imagery in the following examples:

Roman authorities claimed that Christians: “… burn with incestuous passions…with unspeakable lust they copulate in random unions…”

Medieval art depicts the Last Judgment with detailed scenes of naked bodies subjected to (almost) inconceivable torture. The blessed, however, will enjoy these scenes. Saint Thomas Aquinas declared that in Heaven, “…a perfect view is granted them of the tortures of the damned.”

The greatest classic work of medieval literature, Dante’s Divine Comedy, especially the Inferno, has dozens of examples of the most creative punishments. Here is one of my favorites:

The tears of all these sinners down their backs

Were flowing, trickling through their buttocks’ crack.

But Catholics did have a rich tradition of liturgy, ritual, incense, stained-glass images, sculpture and music (for centuries their were no pews in churches; people danced in church). There was a strong, if conflicted appreciation of the feminine principle in the worship of the Virgin Mary. And individuals were confidant of a first-rate afterlife if they followed the strictures of the church.

Protestantism uprooted almost all of this, including the feminine principle. Martin Luther preached, “Ye shall sing no more praises to Our Lady, only to our Lord.” It gave the individual worshipper a personal relationship to God, but it took away his imagination. That is, in leaving him in the state of anxiety I have described, it took away all but his natural, erotic nature, which now had nowhere to go but toward his paranoid imagination.

And there was no longer a place for images. Within a hundred years, Puritans under Oliver Cromwell were desecrating the artwork in thousands of English churches, continuing a tradition of iconoclasm dating back to Byzantium, Islam and the Biblical hatred of idolatry. This tradition would resurface in their twentieth century crusades against pornography and gay marriage – and in their obsession with the images that have always lain just under the surface.

And the most basic characteristic that they projected onto the Other has been its Dionysian refusal to restrain its own animal impulses. “The Devil,” said John Milton, “has the best music.”

So when Eighteenth-century evangelist Jonathan Edwards continued the old fire-and-brimstone tradition (“The sight of hell-torments will exalt the happiness of the saints forever…”), his audiences could both shiver in fright for themselves and also righteously condemn their neighbors.

Part Two of this essay will invite you to (carefully) enter the minds of some of our contemporary Puritans.