The Weeping Woman — Part One

“Don’t go near the water, don’t go out at night,” mothers caution their children near the Rio Grande. They are protecting their children from a different threat than accidentally falling in; they’re talking about being snatched up or sucked in by La Llorona. She is the threatened punishment, the Hispanic boogeyman, of naughty, disobedient children. But she is more. She comes in the dark, on the wind, seeking that which is forever lost to her, crying for her lost children, or seeking vengeance upon the innocent. Sometimes she appears as a skeleton, more often as a beautiful woman, and sometimes she deceives her victims by appearing as someone familiar to them.

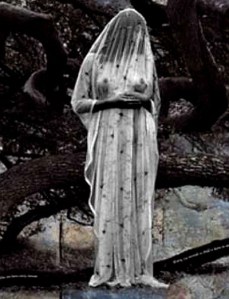

The legend of La Llorona (pronounced “Lah yoh ROH nah”), the Weeping Woman, has been a part of Hispanic legend for at least 500 years. The tall, thin, beautiful spirit with long black hair and a white gown, roams the rivers and creeks, wailing into the night, searching for children to drag to a watery grave.

There are many versions of the story, but in all of them she is the spirit is of a mother who drowned her children and now spends eternity searching for them. In the most common version, the beautiful Maria married a wealthy man. However, after she bore him two sons, he returned to a life of womanizing and alcohol, often leaving her for months at a time. When he did return home, it was only to visit his children. Maria began to feel resentment toward them. One evening, as Maria was strolling with them near the river, he came by in a carriage with an elegant lady beside him. He stopped and spoke to his children, but ignored Maria, and then left. Devastated, Maria went into a terrible rage, turning against her children. She seized them and threw them into the river. As they disappeared down stream, she realized what she had done and ran down the bank to save them, but it was too late.

Maria broke down into inconsolable grief, mourning them day and night, calling out “Mis ninos, mis ninos,” refusing to eat, wandering the riverside, soiling her white gown. She grew thinner and appeared taller until she looked like a walking skeleton, until she finally died on the banks of the river. Not long after, her restless spirit began to walk the banks of the river when darkness fell. Her weeping and wailing became a curse of the night and people began to be afraid to go out after dark. She was said to have been seen drifting between the trees along the shoreline or floating on the current with her long white gown spread out upon the waters. On many a dark night people would see her walking along the riverbank and crying for her children. And so they no longer spoke of her as Maria, but rather as La Llorona, the weeping woman.

In another version she finally threw herself into the river at the very spot where she had murdered her children. In her madness the spirit has completely forgotten what her children looked like, so she calls out for all children. Whenever she finds a child alone in the dark, near the water, she drags it screaming to a watery grave.

In a third variant of the tale, Maria is seduced by a wealthy man, who abandons her once she becomes pregnant. She discards the newborn by throwing it into a river and dies shortly afterward. When she appears at the Heavenly Gates, St. Peter tells her that since she lived a mostly blameless life, she will be allowed to enter Paradise—but only if she brings with her the soul of her child. She is condemned, therefore, to wander the Earth searching for it.

A fourth version: She is married and the mother of twin boys. As the priest is baptizing them, a company of soldiers marches past. One of the children keeps his eyes on the priest, while the other turns his head to watch the soldiers. The mother takes this as an omen — one of her sons is destined to be a priest, the other a soldier. In Spanish Mexico, to the common people soldiers were a symbol of oppression, not of benevolence. As she cannot, later, remember which of the boys turned to look at the soldiers, she drowns both, with the same result as the other stories.

The legend has become part of Hispanic culture from Montana to Central America, and the large numbers of sightings – and the shocking but not infrequent reports of actual women who murder their children – have blurred the boundaries between myth and reality. Here is another version: A young man is walking along Austin’s East 6th Street when he sees a very attractive prostitute dressed in bright red, sobbing her heart out. He approaches and asks what is wrong. She doesn’t reply, but turns toward him. Instead of the beautiful face he expects, her face is that of a donkey—and her open jaws lunge for his throat. The ‘donkey woman’ is a common Hispanic folk-tale. Only in Austin, however, is she known as la Llorona.