We’ve seen some of the political, racial, economic and religious factors that determined an immigrant’s status as he or she attempted to enter the U.S. But what happened next? How did one become American? And, especially in the great expansion of population between 1880 and 1920, how did non-Anglo-Saxon, non-Northern European, non-Protestant immigrants rise in status from conditionally white to fully white? They did so – and still do – by taking on WASP values, embodying the myth of the melting pot: individualism; work ethic; delay of gratification; restrained impulsivity in sexuality, culture and religion; positivity; celebration of youth over elders; and, eventually, the sense of belonging to something greater than themselves. They gave up their ethnic identities and took on the mantel of nationalism.

For some this involved converting to Protestantism and gradually joining those who were moving up the social/religious/class ladder, from Baptist to Methodist and upwards toward Presbyterian, if possible.

Indeed, the whitewashing process began as soon as they disembarked at Ellis Island. Countless thousands of people discovered that their ancestral surnames (if long and unpronounceable) were being “Anglicized.” My wife’s grandfather, for example, had a multi-syllable Polish surname, something like “Distriallatsky,” which some joker of an immigration official arbitrarily changed to “Distiller.”

By 1940, most Japanese-Americans, primarily first- and second-generation, had taken on those values. But history made them into another special case. America fought a race war in the Pacific.

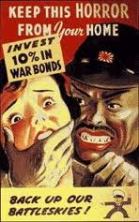

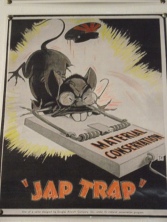

Mendacious posters of ape-like “Japs” raping white women helped mobilize bellicosity and led to a savagery by U.S. soldiers against the Japanese that they rarely exhibited against the Germans.

Historian Richard Slotkin sees World War Two films such as Bataan as the source of the “melting pot platoon,” a cinematic convention that symbolized “an American community that did not yet exist.” However, he notes that ethnic and racial harmony within this platoon is predicated upon racist hatred for the Japanese enemy:

…the emotion which enables the platoon to transcend racial prejudice is itself a virulent expression of racial hatred…The final heat which blends the ingredients of the melting pot is rage against an enemy which is fully dehumanized as a race of ‘dirty monkeys.’

At home, the government herded over 110,000 Japanese-Americans into concentration camps. They had become the new outer Other, but their prisoner status, for a time, also made them into the new inner Other.

Ultimately, Japanese-Americans were too few – and too restrained in their behavior – to carry the role of internal Other for long. Blacks, who were far more numerous, widespread and impoverished, remained the ideal scapegoat.

For Caucasians, this process of becoming fully white always, inevitably involves vaulting past black and brown people in socio-economic status. Even so-called impoverished “trailer trash” and “hillbillies” naturally and unconsciously assume the considerable benefits of their skin color, regardless of what writers such as J.D. Vance and Arlie Hochschild, in their otherwise compassionate efforts to explain Trump supporters, seem to claim.

We must constantly remember the shadow side of the Protestant Ethic, that aspect of white privilege that sees poor blacks and browns, and even whites, as being lazy and therefore undeserving of a better life. When Jerry Falwell said, “This is America. If you’re not a success, it’s your own fault,” he was clearly implying that was true even if you were born into poverty. They – not all of them, and usually not consciously – become racists, and they turn to politicians who promise to protect that privilege – including Bill Clinton, who first promised to “end welfare as we have come to know it.”

In a curious twist of historical and psychological factors, where thinking does seem to create reality, we could argue that Americans are, in a sense, genetically self-selected toward our mania for self-improvement. Those who strive, risk and compete, who chafe most under restrictions, have always made up a disproportionate number of immigrants, if not refugees. Arriving here, they continually reinforce the myths of progress and positive intentions. Here is a statement of the classic immigrant narrative, by a man named Enrique, who arrived as a young Mexican, encountered terrible discrimination, worked at menial jobs (often leaving a day shift at one job to go to a night shift at another), and through sheer will power made a good life in America:

He who has enough desire succeeds. He learns, if you don’t want to succeed, it’s your problem, because no one’s going to come and solve your problems for you.

Upon hearing his story (told, among others, by Garth Gilchrist in his fine radio series The Experience of Immigration: Telling Our Stories), our first reaction is positive. We feel good about and for him, as well we should, given the struggles and mistreatment he endured at each phase of his journey. But then the mythologist in us realizes how close his statement is to the Falwell quote above. This good man has fully embodied our essential myths of individualism and victim-blaming.

If we project his story into the future using the model of the first half of the twentieth century, we imagine Enrique achieving the Dream, starting his own business and a family, becoming a citizen, bringing his parents from Mexico, buying a home in the suburbs, etc. But the narrative also predicts that his children will speak English as their first language, and his grandchildren will not speak Spanish at all.

The myth has another aspect: radical individualism. After 1920, and especially after 1945, many ethnic whites entered the middle class. But narratives soon arose in which each immigrant family had done so alone. All of the social welfare programs, the voluntary associations, the settlement houses and the mass political struggles of twenty million people were wiped from the collective memory in order to serve the older myth of the solitary Protestant individual who rises by his own bootstraps and proves his self-worth before an enigmatic God. “Collective struggle,” said Tom Hayden, “is almost entirely missing from our national immigrant myth.”

And when any individual, even a poor Latino, can believe that “if you don’t want to succeed, it’s your problem,” then in America it is a simple step to “…If you’re not a success, it’s your own fault,” and an even simpler step to accepting and internalizing the propaganda. Tragically, many children of immigrants and refugees have followed their belief in their own self-improvement by condemning the poor and voting against government assistance programs. The past two generations are a perfect example. Some nine million Americans, many of whom were immigrants themselves, took advantage of the post-war G.I. Bill – one of two greatest welfare programs in world history – and later supported politicians who denied similar supports to their own grandchildren.