Sociologist Calvin Hernton wrote in 1966 that the image of the black sexual beast was so extreme in the mind of the racist that he had to eradicate it, yet so powerful that he worshipped it:

In taking the Black man’s genitals, the hooded men in white are amputating that portion of themselves which they secretly consider vile, filthy, and most of all, inadequate…(they) hope to acquire the grotesque powers they have assigned to the Negro phallus, which they symbolically extol by the act of destroying it.

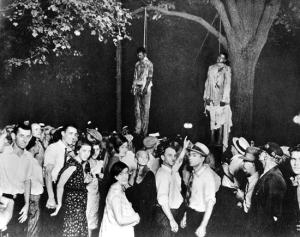

The threat of lynching kept both black men and white women in their places in the rigid southern hierarchies of race and gender. Elites knew that racial violence kept poor blacks and whites from uniting politically. Orlando Patterson, however, asks that we look more deeply into the sacrificial nature of lynching. Of five thousand cases reported between 1880 and 1930 – twice a week for fifty years – at least 40% appear to have most of the attributes of literal human sacrifice, the communal ritual that identified certain individuals as the source of the community’s problems and eliminated them, slowly and carefully, in public ceremonies.

Lynchings were very often not spontaneous mob-violence, nor were they quick and clean; they were carefully orchestrated events. All social classes participated. Take careful note that clergymen usually presided, and that Sunday was the favorite day. The site, chosen in advance and advertised in newspapers, often even before the victim was apprehended, was usually a tree in the center of the community. For millennia, trees had been sacred to pagans and then to Christians. Both Adam’s fall and Christ’s death were associated with tree-symbols. Christianity itself had been founded upon a human sacrifice.

Since white supremacy was a religion, wrote theologian James Sellers, all threats to it took on mythic importance. “Segregation is a system of belief that would protect its devotees from…‘the powers of death and destruction’…It therefore becomes a holy path, complete with commandments, priests, theologians…” The question of actual guilt was often quite irrelevant. If the mob couldn’t apprehend the accused man, they’d randomly select one of his kinsmen for the sacrifice. Often, they ritually tortured him for hours before burning him at the stake.

Then they distributed his remains like religious relics, for his death and dismemberment had cleansed and unified them.

The myth of the Old South, writes Patterson, stated that the presence of the Other, not a slavery-based economy, had caused its shameful defeat. The ex-slave symbolized both violence and sin to an obsessed society. He was “obviously” enslaved to the flesh, and his skin invited a fusion of racial and religious symbolism. His “black” malignancy was to the body politic what Satan was to the soul. “The central ritual of this version of the Southern civil religion…was the human sacrifice of the lynch mob.”

Reading of such astonishing brutality, we recall the scene in The Bacchae when the crazed Agave and her sisters dismembered Pentheus:

…shrieking in triumph. One tore off an arm, another a foot still warm in its shoe. His ribs were clawed clean of flesh and every hand was smeared with blood…

And we recall the delight in detailed imagery taken by Puritan chroniclers of an Indian massacre in 1636:

…to see them thus frying in the fryer, and the streams of blood quenching the same, and horrible was the stincke and sente there of, but the victory seemed a sweete sacrifice…

Approaching the question of Dionysus in America forces us to encounter the potentials for horror as well as ecstasy that lie within us. We must first know who we have been – and still are – before we can imagine what we might someday be; the ghosts of the past require this. In 1899, before torturing him, ten thousand Texans paraded their black victim on a carnival float, like the King of Fools, like Dionysus in the Anthesteria, or like Christ at Calvary. Patterson writes, “…the burning cross distilled it all: sacrificed Negro joined by the torch with sacrificed Christ, burnt together and discarded…”

Race has continued to be the subtext of both national politics and the economy. As the Founders had done in 1776, Franklin Roosevelt unified northern liberals and southern conservatives in the 1930s. But, like the Founders, he had to maintain silence on race, fearing that his coalition would disintegrate. Between 1882 and 1968, Southern politicians demonstrated their power by defeating over two hundred anti-lynching bills.

Now, Senator Orrin Hatch explains, apparently without irony, exactly how we perpetuate our sense of innocence: “Capital punishment is our society’s recognition of the sanctity of human life.” Nearly alone in the world, America executes people – 80% of them minorities – to dramatize our disapproval of violence, even though over 130 Death Row inmates have been exonerated since 1972. Race, especially if the accused is black and the victim is white, remains the overwhelmingly primary factor in death penalty decisions.

Such attitudes survive because black men represent the violence that whites can’t admit is a core part of the American soul. For over seventy years, lynching was the perfect symbolic tool to expiate it. As recently as 1998, white supremacists dragged a black man to death behind their truck. “Today,” writes Patterson, “ we no longer lynch in public rituals supervised by local clergymen. Instead, the state hires the hangman to do it.” More on that comment later.