THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT In AMERICAN MYTH

Part One: The Mythological and Psychological Background

Southern trees bear strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees…

- Abel Meeropol

Myths are the stories people tell about themselves about themselves that help them to make sense of the great contradictions in life. Often, even stories that seem to be about other people turn out to be really about those people (or nations) who are privileged to tell the stories. The story of America is, to a great extent, one of idealistic people, innocent of all sin, who sought out new land to live in freedom and opportunity, and of how they gradually extended those blessings to the world. It’s a story about white people, and it has a large shadow.

The great majority of African Americans, those who have been forced to bear the projection of the white unconscious, understand that the subtext of almost all of our domestic issues – and much of our foreign policies – is America’s original sin, its fatal flaw, race. For sixty years, polls have consistently shown that most white people do not share this view.

As a writer on social issues, let me state my opinion as clearly as I can: from the perspective of the myth of American innocence, any social, economic or political commentary that does not begin by acknowledging this fact is either hopelessly ignorant or deliberately complicit with the aims of the empire and with assumptions of white supremacy.

When we speak of American exceptionalism, we have to understand that America remains at heart a puritan nation, and that the worst of all sins to the Puritan is lack of self-control. Even though studies consistently show that similar percentages of whites and blacks engage in sex, drugs and violence, large numbers of whites still believe the old stereotypes that blacks are more susceptible to such “vices.” This allows whites, wrote Ralph Ellison, “…to be at home in the vast unknown world of America.”

America has had countless scapegoats, but why are we periodically compelled to lynch only one of them? After 350 years of mythic instruction, popular thinking among white people remains polarized along racial lines: civilized vs. primitive, abstinence vs. promiscuity and sobriety vs. intoxication. These pairs of opposites are all forms of a more fundamental opposition between composure and impulsivity (or in mythic imagery, between the ancient Greek gods Apollo and Dionysus). Whiteness, as the civilized, the abstinent, the sober and the composed, is the baseline definition of the innocent community, and blackness, as all those opposites, is the Other.

Othering is not logical. As with archetypes, when one pole of a stereotype is activated, so is its opposite. Even as they perceive blacks as unable to control their desires, large majorities of whites still accuse them of the Puritan’s second worst sin, laziness. Two thirds of white people still tell pollsters that the problems suffered by blacks are due to their preference for welfare over work. This is an odd claim, writes Tim Wise, “…seeing as how five out of six blacks don’t receive any.”

When mythic narratives collapse, when large numbers of people stop believing, they can replace archetypes with stereotypes in their search for something new to believe in. The next step in scapegoating is to manipulate the fear that those who can’t control their desires – or are too lazy to be productive – will entice everyone else to emulate them, that middle-class whites might not be able to resist temptation.

What does this fear of temptation say about white people? It implies that their carefully constructed veneers of innocence, progress, racial superiority, masculinity and self-control are eggshell-thin. At a deeper level, however, it implies envy of those whom the dominant culture, for its own purposes, has designated as more childlike and more in touch with the needs of their bodies.

And envy points toward something even deeper, the unconscious desire for healing. But healing, as something beyond simplistic notions of regeneration, as initiation into self-knowledge, implies the death of what no longer works. The soul desires this more than anything, and the ego fears this more than anything. As James Baldwin wrote,

Any real change implies the breakup of the world as one has always known it, the loss of all that gave one an identity, the end of safety.

And this is precisely why, all across the world, the indigenous imagination has given us stories about mythic figures such as Dionysus, the god of wine and madness, the god who called all those values of respectability, sobriety and decorum into question. And the more a culture holds to those values, the more it is likely to call up a Dionysian figure from its own national unconscious as compensation.

The Black man is America’s modern Dionysus. Like the enigmatic outsider of Euripides’ 4th-century B.C. play The Bacchae, he comes from beyond the gates to liberate the women, to lead them to the mountains to dance among themselves, free of patriarchal control. And in the fever dreams of the white supremacist, he threatens to lead the children away like another outsider, the Pied Piper.

Whites project the stereotyped characteristics of American Dionysus upon blacks because the heritage of Puritanism does not allow them to fully embody those characteristics themselves. But – we must say this repeatedly – just below the negative judgments and hatred of the Other lies envy of those who appear to be comfortable in their bodies and unrestrained in their desires. In a culture that elevates the dry, masculine, Apollonian virtues of spirit over the wet, feminine and Dionysian, African Americans proudly use the word soul to define their music and culture in contrast to the dominant religious and cultural values.

Part Two: Red, White and Black

It is appalling that the most segregated hour of Christian America is eleven o’clock on Sunday morning. – Martin Luther King, Jr.

The genocide of the Native Americans (“the outer Other”) created two problems for the white imagination, for its politicians and for its businessmen. First, it literally didn’t leave enough survivors for them to identify as a threat that could motivate white fear. Second, it didn’t leave enough laborers for their plantations. Colonial whites required someone to act both roles. So they uprooted millions of Africans to form the foundation of the Southern economy, and eventually of the Northern economy as well. Much later, despite a long tradition of anti-immigrant hostility, they also imported millions of Latinos to work the jobs that whites would not accept.

As I have written in Chapter Eight of my book Madness at the Gates of the City: The Myth of American Innocence, neither “blackness” nor “whiteness” firmly established themselves in the American mind until the defeat of Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676 in Virginia, when indentured servants of both races challenged the landowners. This was a watershed moment, as historian Theodore Allen wrote:

…laboring-class African-Americans and European-Americans fought side by side for the abolition of slavery…If the plan had succeeded, the history of…America might have taken a much different path.

Previously, there had been little distinction between dark- and light-skinned laborers. Afterwards, Virginia codified its bondage system. In the first of what would be many examples of affirmative action for whites, it replaced the terms “Christian” or “free” with “white,” gave new privileges to Caucasians, removed rights from free blacks and banned interracial marriage. Other laws contributed to what Allen calls the “absolutely unique American form of male supremacism” – the right of any Euro-American to rape any African American without fear of reprisal.

The new allegiance to a narrative of whiteness eliminated most class competition and provided a sub-class of poor whites to intimidate slaves and suppress rebellion. This is how the first American police forces developed – as slave patrols. Copied everywhere, the pattern merged with the myth of racial war: America’s primary model for class distinction (and class conflict) became relations between white planters and black slaves, rather than between rich and poor.

The new system, wrote Allen, insisted on “the social distinction between the poorest member of the oppressor group and any member, however propertied, of the oppressed group.” Eventually, southern class discrimination merged with northern religious stereotyping. Since poverty equaled sinfulness (to Northern Puritans) and black equaled poor (to Southern opportunists), then it became obvious that blackness itself equaled sin.

By 1700, white Americans had a story that evolved into a neo-Calvinistic myth, and the myth told them that their affluence and their privileges were no accident. It told them that their work ethic, enterprising spirit and ability to defer gratification brought them the good things in life, and that the brutal conditions that both black slaves and poor whites lived under were proof of exactly the opposite.

But there was always that shadow, that dark side of the myth of innocence. Regardless of their economic status, whites were motivated to pledge their allegiance to a state that was defined by the perpetual threat of what Freud would later call the “return of the repressed.” In social terms this took the form of slave rebellions and Indian attacks. At the psychological level, it appeared as that constant temptation to reject the Protestant Ethic and dance.

The predatory imagination found the secret to perpetuating itself – as it would in the1870s, 1890s, 1930s, 1950s, 1980s and today – by manipulating the paranoid imagination. There was always the red shadow of the native warrior (later, the red communist) who might swoop down upon the innocent community with no warning, and for no apparent reason. And the black shadow of the hateful slave lurked within that same community.

The ideas of Red, White and Black were born together in the American soul.

Three and a half centuries after Bacon’s Rebellion, scholars still wonder why a strong socialist movement never developed here, as it did in almost every other developed country. One reason is the profoundly influential ideology (again rooted ultimately in Puritanism) of radical individualism. This created, for whites at least, the expectation of perpetual growth, in both spiritual and material terms. As John Steinbeck wrote,

Socialism never took root in America because the poor see themselves not as an exploited proletariat but as temporarily embarrassed millionaires.

A second factor is the overwhelming presence of the Other. Only Americans combined irresistible myths of opportunity and universal freedom – stories that spoke deeply to the soul – with rigid legal systems deliberately intended to divide natural allies. Every time those allies made common cause, opportunistic politicians played the race card. “No other democratic nation,” writes Cornell West, “revels so blatantly in such self-deceptive innocence, such self-paralyzing reluctance to confront the night-side of its own history.

In this thinking, whiteness implies both purity (which demands removal of impurities) and privilege. From 1680 to 2020, no matter how impoverished a white, male American may have felt, he has still heard dozens of subtle messages every day of his life that divide him from the impure. Without racial privilege the concept of whiteness is meaningless. With it, so is working class unity. Throughout American history, white men often have had nothing to call their own except their privilege, yet they have clung to it and supported those whose coded rhetoric has promised to maintain it. The only new addition that Donald Trump (hereafter referred to as “Trumpus”) brought to this story has been to drop the codes.

The process of exclusion and subordination required a massive lie about black inferiority that has been enshrined in our national narrative. “After all,” writes Tim Wise,

…to accept that all men and women were truly equal, while still mightily oppressing large segments of that same national population on the basis of skin color, would be to lay bare the falsity of the American creed.

Three hundred years earlier, the French philosopher Montesquieu wrote,

It is impossible for us to suppose these creatures to be men, because, allowing them to be men, a suspicion would follow that we ourselves are not Christian.

So we have to address the question of religion again. White Southern evangelicals are Trumpus’ essential base, the only sizable group in the country who supported him to the end. In Chapter Eight of my book I wrote:

How did Puritanism continue to grow there long after it had been greatly transformed into the capitalist impulse in the North? As free land became scarce in the east, most immigrants (including thousands of Scots-Irish Presbyterians) headed toward southern and western frontier areas. There, they fought savage wars with the Indians long after New England’s indigenous population had been decimated.

In the Deep South in particular they lived side-by-side with millions of blacks and the constant fear of both race war and sexual predation. In addition, one can imagine that they felt guilt, conscious or not, for participating directly in the systematic dehumanization of the slaves. This meant that rural Southerners, far more than Northerners, were obsessed with evil in their daily lives.

The Bible occupied a prominent place on the frontier. With few educated clergy around, people were often unaware of its symbolic context. It was venerated more than it was read and read more than it was understood. The Bible was often the only book in the house (this situation still prevails in many American homes). The result was a dogmatism and anti-intellectual literalism that became characteristic of this part of the country.

So, while urban Northerners transmuted their self-abnegation into the sense of deferred gratification required to amass wealth, rural Southerners built up their fear of the Other to such a fever pitch that the Devil – and their own sense of sinfulness – remained as constant presences. Belief in predestination died out, but assumptions about Original Sin remained. This meant fear of judgment, repressed sexuality, longing for Apocalypse and an older sense of deferred gratification, not to wealth but to the next life. Obsession with the other world meant dismissal of this one and contempt for political participation. As a result, most fundamentalists didn’t vote until the 1970s.

That situation would not change until Republicans, realizing that they had no real future without bringing in new voters, deliberately motivated evangelicals with the old tactics of racial fear. And fear, we have learned over and over, trumps moral concerns. Since then, the “Solid South” has simply changed its allegiance from Democrat to Republican, with enough electoral votes to prevent or water down any progressive legislation, but now with the addition of millions of fundamentalists who had previously never voted.

Yes, recent demographic changes in Virginia and Georgia have brought political change, but for the most part we can still ask ourselves if the South actually won the Civil War.

Consider the intersection of narratives centering on southern plantations before the 150 years before 1860: the myth of free markets; the myth of the pastoral plantation, with everyone cheerfully playing their role, protected by benevolent masters and Protestant ministers; the myth of pure Southern Womanhood; and the complex images of the slaves, gratefully serving the planters. These stories about the essential goodness of southern culture would go on to provide the background for a post-war myth that has survived for over another 150 years. The myth of the “Lost Cause” warns us that the South will rise again, because it was a tragic mistake of history that it was defeated.

The North itself long held to yet another story, that racial discrimination occurred only in the South. In reality, Northern mobs attacked abolitionists on over two hundred occasions prior to the outbreak of the War.

Psychologist Joel Kovel asserts that there are two kinds of racism. One is the obvious dominative racism that developed in close contact (including the privilege of rape) between master and slave. The second – aversive racism – arose from Puritan associations of blackness with filth and sin. By 1825 Alexis De Tocquevile wrote that prejudice “appears to be stronger in the states that have abolished slavery than in those where it still exists; and nowhere is it so intolerant as in those states where servitude has never been known.”

Indeed, New England had about 13,000 slaves in 1750. In 1720, New York City’s population of seven thousand included 1,600 blacks, most of them slaves. Not until 1664 (22 years after Massachusetts) did Maryland declare that all blacks held in the colony and all those imported in the future would serve for life, as would their offspring. And the two colonies with the strongest religious foundations – Massachusetts and Pennsylvania – were the ones that first outlawed “miscegenation.”

When northern states expanded the voting franchise for whites in the 1830s, most of them explicitly abolished it for blacks. Later, several states including Indiana and Illinois literally banned all blacks from entering. Oregon (1859), however, was the only free state admitted to the Union with a racial exclusion clause in its constitution. The ban remained in place until 1927. Well into the 1950s (as any black entertainer, athlete or travelling businessman could attest), thousands of “sundown towns” in thirty states prevented blacks from residing overnight on pain of arrest or worse.

But let’s return our focus to the South. As whiteness took on increasing significance, so did the fear of “mongrelization.” Below the fear, however, was envy. And below that was the desire to achieve real healing and authentic psychological integration. To cover up such unacceptable fantasies, whites projected their desires onto blacks. Even the great humanist (and, we have learned, willing race mongrelizer) Thomas Jefferson apparently felt that black men had a preference for white women over black women “as uniformly…as the preference of the Oran-utan for the black woman over those of his own species.” Indeed.

As the Native American population (the Outer Other) east of the Appalachian Mountains shrunk into relative insignificance, due to genocide and ethnic cleansing, African Americans assumed the role of the Inner Other. What (in the white mind) were their characteristics? First, they were childish, lazy and unreliable – the shadow of the Protestant Ethic. It was necessary to force them to be productive. White performers began to wear blackface in the 1840s. LeRoi Jones (later known as Amiri Baraka) wrote,

… the only consistent way of justifying what had been done to him – now that he had reached what can be called a post-bestial stage – was to demonstrate the ridiculousness of his inability to act as a “normal” human being.

Whites needed to believe that blacks were slow, dumb and happy, so many blacks assumed the persona and acted that way. Whites created fictional characters – from Jim Crow to Gone With the Wind’s Mammy: loveable and loyal, yet lacking any concern for intellect or freedom. Blackface minstrelsy was America’s primary form of entertainment throughout the nineteenth century. Forms of it (Amos ‘n Andy) survived into the 1950s, tutoring millions in racist stereotyping. But it provided something else. By vicariously impersonating blacks, as Michael Ventura has written, “white Americans could briefly inhabit their own bodies.”

A second aspect of the story contradicted the first, but no one noticed, since othering is not logical. This Other was intensely sexual and aggressive. Like Dionysus, he might sneak in and corrupt the children. Class society assigns the mind to the masters and the body to the servants. In racially homogeneous societies, where the leaders racially resemble the followers, these images are not mutually exclusive. The poor can potentially join the elite. But in racial caste systems masters are physically different from servants, and the images are mutually exclusive. In America the old mind/body division coincided with the racial gulf, and this distinction became sacred.

It took abstraction to new levels. Countless whites, inheritors of the Puritan imagination, hated the body’s needs and feared that they might be judged by how well they controlled them. Here is a clue to slavery’s appeal that goes beyond economics and questions of privilege. This terror, writes Ventura, “…was compacted into a tension that gave Western man the need to control every body he found.” In slavery, “the body could be both reviled and controlled.”

Third, it was necessary to confine this Black Other of the South, unlike the external, Red Other (now exiled primarily west of the Mississippi River), within the gates of the innocent community. Whites could savagely defend their women from him, but they couldn’t afford to exterminate or isolate him in concentration camps (otherwise known as reservations), because he was critical to economic prosperity. Slavery fit the model of an internal Other that had appeared earlier in the Witch craze. White Europeans had long been used to these stereotypes: for hundreds of years before the discovery of the New World, they had seen Jews as the internal Other and Muslims as the external Other.

After emancipation, racism remained the foundation of a political economy predicated upon fear, the constant threat (and temptation) of violence, division of the working class and further refinements of whiteness. The law long assumed that blacks were persons with any African ancestry. The “one-drop rule,” used by no other nation, made one a black person. “Octoroons,” who had seven white great-grandparents out of eight, were considered to be black.

Curiously, in the case of Native American admixture with whites, courts enforced the one-drop rule more selectively. They recognized the “Pocahontas exception” because many influential Virginia families claimed descent from Pocahontas, a fundamental and positive character in America’s origin myth. To avoid classifying them as non-white the Assembly declared that a person could be considered white as long as they had no more than one-sixteenth Indian blood.

For decades, despite many exceptions, one of the primary characteristics of whiteness across large swaths of the country was the simple fact of legal freedom. This changed quickly after 1865. So new laws were enacted that prevented most blacks from acquiring western land, thus keeping them as de facto slaves in the south. Homesteading became a privilege reserved for white people, another example of affirmative action. In the southwest, similar systems targeted Latinos. No wonder our picture of the hardy “pioneers” who settled the west is lily-white.

When poor whites and blacks again threatened to unite, the Jim Crow system arose, held in place by the threat of large-scale, domestic terrorism. Between 1868 and 1871, the Ku Klux Klan murdered over two thousand Americans and intimidated countless others. In the 1890s, when workers and farmers organized the Populist Movement, there were 200 lynchings per year. The dream of unity collapsed (as it would again in the 1970s) under the fear and the temptation to identify as white. This systemic violence might have provoked more outrage but for a rationale that silenced criticism. Sexuality was a means of reasserting both white control over blacks and male domination of women, even though fewer than a quarter of lynchings resulted from allegations of sexual assault.

When agriculture mechanized and the South no longer required so many cheap agricultural workers, many blacks left, only to be confined within northern ghettoes, where nearly equally severe conditions resulted in the poverty and violence that whites associated them with. By 1900 the mythmakers had succeeded: whites commonly believed that blacks hadn’t been ready for freedom because, like Dionysus, they couldn’t “sacrifice their lusts.”

Like the ancient Athenians, Victorian Americans saw themselves as Apollonian, hardworking, rational and progressive. Meanwhile, they had enshrined the Other in a form the Greeks would have recognized but burdened with Christian sinfulness. “Enshrined” seems to be the proper term here: there was (and is) simply no possibility of worshipping such a deeply corrupted version of the Christ without imagining an equally corrupt, “evil twin.” For more on this question, see Chapter Nine of my book.

There was no place for him within the pure American psyche, and to a great extent, the economy, but it was still necessary to keep him close. To several generations of white immigrants, the descendants of the slaves, in both their stereotyped, earthy physicality and the implied threat of their vengeance became America’s dark incarnation of Dionysus, our collectively repressed memory and imagination. Since whites desperately needed to project him, to see him, they created exactly those conditions – segregation and discrimination – that dehumanized him and fostered behavior that whites could demonize.

White Americans filled their imaginary underworld with monsters: the outer, Red Other (now transformed from Indians to communists) and the inner, Black Other. In 1960, Baldwin concluded,

We would never, never allow Negroes to starve, to grow bitter, and to die in ghettos all over the country if we were not driven by some nameless fear that has nothing to do with Negroes…most white people imagine that (what) they can salvage from the storm of life is really, in sum, their innocence.

Part Three: Conflicting Images of the Other in the South in the 1960s

The old joke comes close to explaining the stunning combination of racial animosity and innocent ignorance that white Americans accepted as reality in the early 1960s. Only about 6% approved of interracial marriage, while 84% were convinced that blacks had equal educational opportunity.

Even though anti-segregation protests had been happening for years, most whites had been unaware of a national movement for racial freedom until most acquired televisions. Rather abruptly, it seemed that by sitting in at lunch counters across the South, the Other was stepping in from his and her internal exile, demanding to sit at the same the table as the master. Insisting that neither freedom nor equality was possible without the other, the Civil Rights Movement defined freedom in terms of inclusion. But for Southern whites (and later for Northern whites as well), inclusion meant something that absolutely threatened their myth of innocence: meeting the Other on equal terms.

Are you old enough to remember those “black-and-white” photos and newsreel films of the demonstrations and attempts to desegregate schools? Find some videos online and notice several things. First: the dignity, determination, religious fervor and conservative attire of the African Americans. Second: the presence of northern whites accompanying them. Then, as the camera pans back, we comprehend the broader context: hundreds of local whites, brought to the scene by the possibility of seeing or participating in violence – with fury or fear on their faces.

We see the burning crosses, the police dogs and the fire hoses.

But we also see leather-clad toughs and housewives in high heels taunting the marchers with astonishing profanity.

What we don’t see is the 350-year legacy of fear that turned working-class whites and blacks into adversaries. We don’t see the religious conditioning that divided whites internally, against their own bodies. We don’t see the heritage of alienation that required the construction of an entire race of scapegoats so that whites could cling to their privilege and their innocence.

Still, the demonstrators are merely sitting quietly, singing or marching in silence. Why is there such rage on the white faces? Certainly, blacks are demanding equality and whites fear some economic loss. But furious, violent, out-of-control rage?

Perhaps it is because the blacks aren’t “shuffling and jiving,” lowering their heads or stepping off the sidewalks to let them pass. Perhaps because they are no longer presenting the false persona of childish or contented servant. Perhaps it is because some are looking the whites directly in the eye for the first time in anyone’s memory, refusing to call them “sir.”

I propose that then (and, sadly, 60 years later) the whites, whether “crackers” or prosperous shopkeepers, were facing a profound dilemma. They could no longer successfully project self-contempt for their sexuality, their bodily connection to the old pagan gods, to Dionysus, onto the blacks. Forced to contemplate people just as self-controlled as themselves, and quite often more so, they faced an Other who was themselves.

In another context, the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish wrote:

…and they searched his prison

but could only see themselves in chains.

White violence wasn’t merely intended to disrupt the marches. Here is the secret: the whites were trying to incite the blacks into retaliating in anger, to move their bodies, to dance, or at least to lower their heads. They were hoping to provoke them into re-inhabiting the psychic space of the Other, so that they, the whites, could be free of the oppressive weight of self-awareness. Whites were desperate to remove it from their own shoulders and place it back where it belonged.

But how could they do that when (a few years later) blacks were chanting, “Black is beautiful?” If the Other was everything that the citizen of the polis was not, and the Other was self-controlled – or beautiful – what did that make the citizen? And if the citizen has his innocent persona stripped away, what then rises to the surface? How could it not be self-hatred? Rather than facing it, Americans have long learned to channel their darkness into religion, substance abuse, consumerism, race hatred and a unique capacity to seek out and enjoy vicarious violence.

The miracle of the early 1960s is not the legal freedoms and voting rights won by African-Americans, but the fact that they could hold so much hope amid such hatred without retaliating. The movement eventually failed when they could no longer restrain their own rage within the ritual container of pacifist religion and finally struck back.

Langston Hughes wrote,

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

Like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore–

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over–

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

So much had been promised – even poor families now had TV and could see what the Good Life appeared to be – and so little was delivered. Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty failed because his other war against Vietnam was bankrupting the nation. Historian Milton Viorst wrote, “…rising expectations prevalent in the mid-1960’s had transformed everyday discontent into an angry rejection of the status quo.”

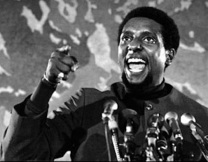

After the Watts riots of 1965 a phrase that perfectly articulated the return of the repressed – Black Power! – first appeared.  In 1967 (ironically the same year that the Supreme Court finally struck down the last Southern laws prohibiting interracial marriage) blacks rioted in 23 cities, leaving scores dead and thousands arrested.

In 1967 (ironically the same year that the Supreme Court finally struck down the last Southern laws prohibiting interracial marriage) blacks rioted in 23 cities, leaving scores dead and thousands arrested.

Once Blacks refused to submit, two things resulted. First, many others – students, women, Native Americans, Latinos, prisoners, disabled people, environmentalists and gays – also rose up. 1968 was a surreal explosion of televised war carnage, anti-draft demonstrations, political assassinations, ferocious riots and mayhem at the Chicago convention.

Secondly, public opinion, which had solidly favored civil rights, began to change. TV showed not only the rage but also ecstatic images of blacks looting only blocks from the White House. Violence was familiar, but this was new: the internal Other would no longer serve as primary victim of American violence. The white middle class was losing jobs and feeling disenchanted, exhausted, victimized and vulnerable to reactionary backlash.

Hollywood saw the opening and responded with vigilante movies (starring Charles Bronson, Clint Eastwood and Chuck Norris) in which solitary redeemer-heroes, in an old mythic format, took matters into their own hands and cleaned up the urban chaos with brutal violence. Everyone knew what “urban” meant. And everyone was familiar with the mythic themes that the film Fort Apache, the Bronx invoked.

Conservatives, also seeing an opening, were quick to perceive class differences between white anti-war activists and returning soldiers, as well as the police they were fighting. When the National Guard exploded in violence at Kent State in 1970 (few even noticed the black students killed a week later by state police at Jackson State College in Mississippi), the public was outraged at the students, not their killers. Viorst writes that many rejoiced that, “…the act had been done at last…the students deserved what they got.”

“The act” was the murder of the children – white, educated – in a nationally televised, ritual sacrifice of a new scapegoat. Enough youth had rejected American values so completely that, to the shocked elders, it seemed that they had become the Other. They were acting “just like blacks,” and this, finally, was unacceptable.

Although America had been killing the children in Vietnam for years and in the ghettoes for generations, here was an unmistakable response from their elders: Your purpose is to be like the fathers, or to die. Shortly after Kent State, while students were striking at 450 campuses, thugs attacked peaceful demonstrators while New York City police watched.

Years later, after exonerating the students, Kent State commissioned a monument. However, it rejected sculptor George Segal’s model of Abraham  poised with a knife over Isaac.

poised with a knife over Isaac.

The myth of innocence had weathered a series of terrible shocks, but its image of the internal Other had survived. Whites no longer perceived blacks as discreet, religious, non-violent saints who were shaming America into remembering its values. They were now dashiki-wearing, long-haired, foul-mouthed terrorists who ruled the city streets at night – “Black Panthers.” And the panther was Dionysus’ animal. The Black man once again carried the projection of America’s Dionysus. And one could well ask, Did the South actually win the Civil War?

Part Four: Fifty Years Later

Martin Luther King’s assassination in April of 1968 marked the end of the Civil Rights movement. What has changed since then? Few would deny that significant, fundamental transformation has occurred in American race relations over these decades. Discrimination is illegal everywhere and blacks can theoretically vote if they want to. A black middle class has developed, and a few have become truly rich. Hundreds of blacks and other minorities have attained elective office and some have achieved real influence in the centers of power. And of course Barack Obama was President.

According to this narrative, the agonizingly long process of acknowledging the Other as part of the polis has concluded. And if the American story is about anything, it is about progress. The Civil Rights movement succeeded! Obama was proof that we had completed the transition to a “post-racial” society. Republicans (who had viciously resisted the movement at every single step while it was happening) now adore this narrative, because it allows them to justify slashing funds for welfare and other aspects of the New Deal. Democrats love it because it allows them to ignore or co-opt the minorities who make up their actual base.

Part of this narrative involves creating a new variant on the myth of perpetual American progress that moves in a straight line from exclusion of the Other to inclusion. It involves valorizing Dr. King while covering up the history of the true radical and outspoken anti-war activist who would have been bitterly disappointed by Obama’s subservience to the American empire. It involves denying how the liberal establishment hated him in his last year.

And it means that reactionaries (it’s no longer accurate or appropriate to use the word “conservative”) in government and media have been able to justify all manner of cruel legislation and new forms of voter suppression with the absurd notion that since discrimination is now illegal, special voter protections are only longer needed. Do I exaggerate? In 2013 the Supreme Court struck down the central features of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 using exactly this language, and the decision quickly resulted in Trumpus’ election.

These things are obvious to African Americans. White Americans, however, have proven over and over that their perceptions about race are hopelessly out of line, both with those of blacks as well as with the statistics.

African Americans know that much of their economic and social progress has stalled or even reversed; that the war on drugs killed tens of thousands of their people; that hundreds of thousands are in prison; that literally millions of them have lost the right to vote; that school segregation is worse than it was twenty tears ago; that the financial crisis of 2008 impacted blacks disproportionately, and that the banks had deliberately targeted them; that 2020 replicated those conditions; that black mothers in New York City are twelve times as likely to die in childbirth as white mothers; that despite the Black Lives Matter movement, police continue to murder large numbers of unarmed black people without fear of reprisal; that the idea of white privilege finally entered the lexicon, but with little effect; that 87% of blacks believed that Trayvon Martin’s murder was unjustified, while only 33% of whites did; that 30% of whites over 65 still disapprove of interracial marriage; that blacks and whites are still worlds apart when polled on how well things are going ; that arsonists torched some fifty black churches between 1990 and 2017; that the media still regularly portray blacks negatively; that mortgage lenders still discriminate against them; that race (as voter suppression, gerrymandering, computer fraud, voter I.D. laws, new forms of the poll tax and massive, fundamentalist backlash) turned what everyone expected to be a Democratic landslide in 2016 into a social, financial and environmental disaster; and that tens of millions of whites now openly, unashamedly, support blatantly racist politicians.

2016 was what I called a “Dionysian Moment” in which the old Puritan values of self-restraint and the polite hypocrisies of coded rhetoric were finally ejected for someone who “says just what he means,” a man who, from the center of the culture, encouraged every vile hate to come out from the shadows, to be pardoned in advance.

Despite the evidence of progress, one major cultural difference between the America of 1955 and our current condition is this. Then it was possible to shame whites (or enough of them) into behaving themselves; that is, to at least consider acting as if their uniquely professed values of freedom and equality for all were real. Then only a few people felt comfortable enough to voice their bigotry. Now, after several decades of TV saturation, normalization of cruelty, dumbing down of education – and now social media algorithms designed to confirm social biases – it seems to me that the most accurate pejorative we can use to describe Trumpus and his believers is “shameless.”

I’ve written many essays on race in America and on Obama in particular (these are noted at the end), so I’m trying not to repeat myself here. To conclude this one, I want to add an observation that is consistent with my argument in Part Three that in the 1960s Southern whites could not bear the tension of observing an “Other” with whom (in terms of behavior) they might well be identical.

Obama experienced a unique dilemma beginning well before his election. From the right, there was plenty of the predictable (and some not so predictable) racist nonsense. Some critics on the left, however, complained that in attempting to appeal to the middle he simply wasn’t acting “black” enough. Then there were the really loony allegations: he was not an American citizen, he was a secret Muslim, he was a socialist, etc. He wasn’t white enough. It was a branding problem that his handlers struggled with throughout his eight years in office. But at the time, I wrote that like any other candidate hoping to attract major funding, he had been carefully vetted by the Deep State and tasked with the work of shoring up the glaring holes in the fabric of American exceptionalism. Eight years later, I think I was right.

In regard to that brand, Obama, despite his modest family roots, was clearly a well-mannered, rational, dispassionate, Ivy-League educated, cultured, articulate, even brilliant card-carrying member of the upper middle class, and so was his wife. Their children were talented and beautiful; they were the most photogenic Presidential family since the Kennedy Camelot of the early 1960s. They had no scandals, sexual or otherwise. The “darker brother,” in Langston Hughes’ words, had finally arrived “at the table” and “They’ll see how beautiful I am – And be ashamed.”

This created a profound dilemma for countless working-class whites; the old poem was too accurate in its prediction. Throughout their adult lives, they had been subjected to a daily, unending barrage of hysterical fear mongering about the racialized Other that was far more intense than anything their parents had seen in the fifties and sixties. And they experienced eight years of war, job loss caused allegedly by affirmative action (an absolute lie of course, but much easier to digest than the fact that the politicians they’d elected were screwing them) and countless examples in the media of assaults on their sense of white masculine potential; all of which led to an opiate epidemic that by 2016 would kill 50,000 of them per year. Is it any surprise that it was white males who perpetrated almost every one of the 336 mass murders in 2017? That’s right: almost one per day, and almost always white males.

Ironically, the fact that Obama was continuing the financial and military policies of his Republican predecessor seems to have mattered little to the Tea Partiers, Alt-Rightists and Christian extremists who would eventually become Trumpus’ foot soldiers. What mattered to them was branding, symbol, imagery, victimization and race.

To millions of white people, the constant sight of this, yes, privileged family in the seat of power was a daily reminder of how low they had sunk, and that (quite inaccurately, of course) 350 years of injustice were being rectified: the Other was at the table – their table. The shock-jocks seemed to be right. Blacks were replacing them at that table. Polls indicated that white people now actually perceived themselves as more discriminated against than blacks.

Plenty of political writers have analyzed this subject. But I insist on the psychological and mythological approaches, because when we look through these lenses, we can see that little has changed since 1955:

The whites, “crackers” or middle-class, are facing a profound dilemma. They can’t project self-contempt for their sexuality, their bodily connection to the old pagan gods, to Dionysus, onto the blacks. Forced to contemplate people just as self-controlled as themselves, and quite often more so, they face an Other with whom they are identical.

Their perception of Obama – and of the possibility of true racial healing – seems to have been determined on three levels. On one level, the constant media barrage (with massive funding from the Koch brothers and friends) was successful. The shock-jocks and the televangelists repeated the old con, converting disillusionment with the system itself into racial animosity and hatred of immigrants.

But on another level, their spokesmen were, in a sense, unsuccessful. None of the venomous and very thinly veiled racism of Fox News or Republican politicians could incite Obama into retaliating in anger, to re-inhabit that psychic space of the Other, to act like a dangerous, angry black man. By contrast, what they got was a leader who seemed comfortable weeping at the thought of dead (American, not Muslim) children.

…so that they, the whites, could be free of the oppressive weight of awareness…If the Other was everything that the citizen of the polis was not, and the Other was self-controlled – or beautiful – what did that make the citizen?

Hate grew on a third level, out of frustration and denial. I think the dynamic was and is the same as in 1960: we hate them because they’re lazy and dangerous. And we hate them more when they prove that they aren’t.

Trumpus didn’t create any of this. But as a long-time con man and Reality TV star, he was simply smart enough to perceive it and run with it – directly, proudly, arrogantly, with no shame and using only the thinnest of euphemisms – in a way that the Republican establishment had never dared to. Joshua Zeitz writes:

…Trump has also, arguably more than any other candidate for president in the past hundred years (excepting third-party outliers like Strom Thurmond and George Wallace), played to the purely psychological benefits of being white. From his racially laden exhortations about black crime in Chicago and Latino gangs seemingly everywhere, to his attacks on an American-born federal judge of Mexican parentage and on Muslim gold star parents, he has paid the white majority with redemption…Trump might be increasing economic inequality, but at least the working-class whites feel like they belong in Trump’s America.

The other Republican candidates attacked him in the primaries not because he was a racist thug and a bully – they had been doing precisely the same ever since the days of Nixon, only with more restrained hints and innuendo (“urban”, “gang violence”, “welfare queens”, etc) – but more for his style. By comparison, their brands were higher-class, more restrained, in that old Puritan style.

But of course they quickly rallied around their useful idiot when he won, because they sensed the possibility of achieving the reactionary legislation that their corporate sponsors had always demanded. Once in office, he quickly became, as Charles Derber writes, a “fig leaf for the GOP’s Horrific Policies.” And within six months, his public support dwindled down to that base of angry and fundamentalist whites. Why? Because they were the only crowd with an imagination impoverished enough to value race hatred over their own economic self-interest.

And, in an ironic 2021 version of the “return of the repressed,” this crowd remains angry and powerful enough to intimidate most Republican politicians into defending the ex-President against impeachment.

Many analysts predicted that these people would eventually figure out exactly how and where Trumpus and the Republicans had been sticking it to them and move back to the center or even the left. But they failed, and still fail to understand how the perception of white privilege is self-interest. A blogger known as “Forsetti” who grew up among fundamentalists, explains why they won’t:

When you have a belief system that is built on fundamentalism, it isn’t open to outside criticism…Christian, white Americans…are racists…people who deep down in their heart of hearts truly believe they are superior because they are white. Their white God made them in his image and everyone else is a less-than-perfect version, flawed and cursed.

The religion in which I was raised taught this…Non-whites are the color they are because of their sins, or at least the sins of their ancestors. Blacks don’t have dark skin because of where they lived and evolution; they have dark skin because they are cursed. God cursed them for a reason. If God cursed them, treating them as equals would be going against God’s will.

Since facts and reality don’t matter, nothing you say to them will alter their beliefs. “President Obama was born in Kenya, is a secret member of the Muslim Brotherhood who hates white Americans and is going to take away their guns.” I feel ridiculous even writing this, it is so absurd, but it is gospel across large swaths of rural America.

A significant number of rural Americans believe President Obama was in charge when the financial crisis started. An even higher number believe the mortgage crisis was the result of the government forcing banks to give loans to unqualified minorities. It doesn’t matter how untrue both of these are, they are gospel in rural America. Why reevaluate your beliefs and voting patterns when scapegoats are available?

Some have claimed that southern evangelicals first entered the political world after the nation made abortion legal. Randall Balmer, however, shows that the issue that actually aroused them was the same one that had motivated their ancestors to sacrifice themselves by the hundreds in the Civil War: race. Then, and for a hundred years, the issue was “race mixing.” For the next fifty years it was and has continued to be the issue of desegregation allegedly mandated by liberals.

Three years before the attack on the Capitol, half of all white southerners believed that white people were under attack, while 55% of all whites believed that discrimination exists against them. These figures are not mere statistics; they are indications of how deeply ingrained in the American psyche is the idea of victimization. They indicate the enduring strength of American myth.

By the way, if it isn’t perfectly obvious to you that religion is a mere fig leaf concealing their racism (and the fear that lies below it), simply recall that black evangelicals have never shared their opinions or voted with them.

This is what a demythologized world looks like. Our politics and our religion are so utterly corrupted that millions of under-educated people continue to support billionaire con-men who are fleecing them blind but offering a refuge in othering, while millions of other, well-educated people take refuge in another narrative, “Russiagate”, that offers a different kind of refuge: denial.

My articles on Race in General:

— The Mythic Sources of White Rage

— Affirmative Action for Whites

— The Sandy Hook Murders, Innocence and Race in America

— Hands up, Don’t shoot – The Sacrifice of American Dionysus

— Do Black Lives Really Matter?

— Did the South Win the Civil War?

— A Mythologist Looks at the Election of 2016

— The Dionysian Moment: Trump lets the Dogs out

My articles on Obama:

— Obama and the Myth of Innocence

— The Con Man: An American Archetype

— Stories We Tell Each Other About Barack Obama