Part One

Every good deed brings its own punishment. – James Agate

Sometimes the spirit comes through me. I’m not saying this out of pride. I’m simply observing that one when is committed to his art – in my case, writing about historical, political and cultural issues through a mythological lens, when one asks to be a conduit for other voices – when one tries to pay attention – then one had better be prepared for synchronicities. One had better be prepared to drop what one is doing, to sacrifice some trivial pleasure or responsibility, and just listen.

Or watch. The other night, having already planned to see Terrance Malick’s new film A Hidden Life, I discovered the 2016 film Alone in Berlin on Netflix and watched this dramatized true story. A middle-aged German husband and wife, grieving for their son who’d been killed in the war, can no longer passively accept the authority of the Nazi death cult. They leave some 200 handwritten, anti-war postcards all over the city until the Gestapo arrests them. Having offered up their son to the State (in reality it was her brother, but that doesn’t matter), they ultimately sacrifice themselves. Indeed, the film’s ending is a bit ambiguous. Perhaps they want to get caught; perhaps their protest, dangerous as it is, is not enough.

Having offered up their son to the State (in reality it was her brother, but that doesn’t matter), they ultimately sacrifice themselves. Indeed, the film’s ending is a bit ambiguous. Perhaps they want to get caught; perhaps their protest, dangerous as it is, is not enough.

Otto and Elise Hampel were sent to the guillotine in Berlin on April 4th, 1943.

The next day, somewhat shaken by that film, thinking of people who really had sacrificed for their principles, I went for a hike in Oakland’s Mountain View  Cemetery, where a series of random (?) turns took me past the grave of Fred Korematsu, who had refused to cooperate with the government’s internment of his fellow Japanese-American citizens and had fought for decades to clear his name and secure compensation for them. Synchronicity.

Cemetery, where a series of random (?) turns took me past the grave of Fred Korematsu, who had refused to cooperate with the government’s internment of his fellow Japanese-American citizens and had fought for decades to clear his name and secure compensation for them. Synchronicity.

Then, knowing what I was in for (it’s nearly impossible to see a movie these days without already knowing about its plot), I went to my local theater and watched A Hidden Life, another true story of passive resistance to the Nazis.

Franz Jägerstätter is no urban sophisticate but a devout Catholic farmer living an idyllic life in Austria’s Tyrolian mountains.  His village lies below towering peaks shrouded in mist, with green hills rolling to distant horizons. Deep, intense green fills every frame. He and his wife Fani, even after having produced three daughters, are deeply, sensuously in love. In voiceovers he muses, “I thought we could build our nest high up in the trees…Fly away like birds.” Even though the war, its horrors and its moral choices will soon reach them, Fani says, “It seemed no trouble could reach our valley.”

His village lies below towering peaks shrouded in mist, with green hills rolling to distant horizons. Deep, intense green fills every frame. He and his wife Fani, even after having produced three daughters, are deeply, sensuously in love. In voiceovers he muses, “I thought we could build our nest high up in the trees…Fly away like birds.” Even though the war, its horrors and its moral choices will soon reach them, Fani says, “It seemed no trouble could reach our valley.”

I won’t lie; from the first images I was weeping. I’ve been to the Tyrol, and the area certainly is gorgeous. But the film immediately, repeatedly and quite deliberately presents images of such overwhelming natural beauty (later to be contrasted with the meanness of people and institutions) that I fell into a trance, as poet Mark Nepo says, “of wonder and grief”. It seemed clear (to me at least) that the filmmaker was intent on forcing viewers – me – to confront not simply the imminent loss of this fairy-tail family love nest. I was well aware that it was the first week of 2020, that this year may well be our last chance to reverse global warming, that there may well not be a future. We are all on the very edge of losing this beautiful world.

Franz’s faith is absolute. In this age of pedophile priests, racist evangelicals who look forward to the End Times and televangelists who declare you-know-who to be “the Chosen One,” we are a bit shocked to realize that Franz is a real Christian. (By the way, here’s a link to a contemporary American real Christian).

Or perhaps – with all this lush scenery, these intensely verdant meadows and gently flowing waters, all this planting and harvesting, all this much-more-than-Christian sensuality, all this dancing, playing,  touching, kissing, caressing of animals, rolling on the grass, filling the hands with the fertile earth, with the mothers of all mountains in the background – perhaps, just below the surface, these people are true pagans (paganus: hill people). It’s not too much of a stretch to suggest that they are devout Catholics in nearly the same way that syncretistic Haitian vodouisants or Brazilian Candomblers are.

touching, kissing, caressing of animals, rolling on the grass, filling the hands with the fertile earth, with the mothers of all mountains in the background – perhaps, just below the surface, these people are true pagans (paganus: hill people). It’s not too much of a stretch to suggest that they are devout Catholics in nearly the same way that syncretistic Haitian vodouisants or Brazilian Candomblers are.

But Franz gradually concludes that he cannot remain a moral person and also serve in Hitler’s death machine or even sign an oath of allegiance to the Fuhrer, as all Austrian men are required to do. By saying, “No,” Franz, like the Hampels, knows that he could lose everything. This is why Malick spends so much of this very long film dwelling on the family’s profound love of nature and each other. There really is so much at stake, for them and us.

Their Eden eventually becomes a social hell. Franz’s refusal to just go along calls down scorn and condemnation upon his family, because he has forced everyone else in the village to confront the roots of their own identities. Some may be afraid to publicly agree with him, while others quote Hitler, screaming about the evils of immigrants and foreigners in a place where there seems to be none of either. They brand him a traitor, spit on Fani and throw mud at their daughters. Once Franz is transported to prison in far-away Berlin, the other farmers refuse to help Fani with the back-breaking labor of tending the land and livestock. When her cow dies, she and her sister must pull a plow through her field by themselves. What a metaphor.

She ultimately makes her own choice to support his decision, but only after after months of emotional conflict in which everyone in the film, from his mother and his closest friends (who become ex-friends), to his fellow prisoners, his guards, his lawyers and even his judge, plead with him to take the oath. Everyone agrees that his resistance won’t change anything and will come at too high a price for him and his family. And there is a way out: he can be a conscientious objector and serve as a medic in a hospital, if he will only sign. Everyone has their own argument:

The Bishop: “You have a duty to the fatherland. The church tells you so.”

The villagers: “Pride! That’s what it is, Pride!” Your mother will die un-consoled.”

A fellow prisoner: “You can’t change the world; the world is stronger.”

A sadistic guard: “I can do anything I want to you! No one will notice!”

His judge: “Nature has not noticed the sorrow that has come over people.”

His priest: “God doesn’t care what you say, only what is in your heart.”

Fani: “I need you.”

By the end, after Fani’s heart-wrenching final meeting with him in the prison has failed to persuade him, the only man in the film to support him, her father, admits, “Better to suffer injustice than to do it.” Franz, like the Hampels, goes willingly, if with deep sadness, to the guillotine.

A few historical notes: The municipality of Sankt Radegund  at first refused to put his name on a local war memorial and the state did not approve a pension for Fani until 1950. Eventually, several books and films made their names known, and the Vatican beatified Franz in 2007. Fani died in 2013, age 100.

at first refused to put his name on a local war memorial and the state did not approve a pension for Fani until 1950. Eventually, several books and films made their names known, and the Vatican beatified Franz in 2007. Fani died in 2013, age 100.

You can read dozens of reviews of A Hidden Life here. Most are of interest only to other film reviewers and serious film buffs, but a couple of writers observe its religious dimensions. Peter Ranier writes:

Most of the famous religious-themed Hollywood movies…are biblical epics functioning as star-studded illustrated guidebooks to sacred texts… “A Hidden Life” is the antithesis of those epics. It’s an attempt to make the movie itself function as a religious experience. It has a powerful sense of the immanence of life. Franz’s stance is a deeply moral one, but his morality is based on his religious precepts. This is what differentiates “A Hidden Life” from so many Hollywood movies where people, without any religious underpinning, fight for what is right.

“A Hidden Life” is less a story than an experience, a spiritual journey made accessible through light and sound. Malick doesn’t transcend cinema. He sanctifies it.

But it’s the film’s moral dilemma that throws us into such torment. Why, ask so many characters (and viewers), should Franz do the right thing if it changes nothing? What is the value of an unwitnessed sacrifice?

Part Two

Near the snow, near the sun, in the highest fields

See how these names are fêted by the waving grass,

And by the streamers of white cloud,

And whispers of wind in the listening sky;

The names of those who in their lives fought for life,

Who wore at their hearts the fire’s center.

Born of the sun, they traveled a short while towards the sun,

And left the vivid air signed with their honor. — Stephen Spender

As readers, film and TV viewers, students, churchgoers or any other patriotic consumers of our national mythologies, we have long been conditioned to support, praise and even to emulate that vast pantheon of heroes who put themselves in harm’s way to defend the innocent. In the extreme, we venerate those few who are willing to simply die for an ideal. This is one of the major themes of my book, Madness at the Gates of the City: The Myth of American Innocence.

Like almost every man my age, I grew up on John Wayne and Fess Parker’s Davy Crockett, who is last seen dying for freedom at the Alamo, and it’s not easy to remove those images and stories from one’s subconscious. It was easy, however, to forget that Davy’s family was back in Tennessee, and that John Wayne rarely even had a family.

Like almost every man my age, I grew up on John Wayne and Fess Parker’s Davy Crockett, who is last seen dying for freedom at the Alamo, and it’s not easy to remove those images and stories from one’s subconscious. It was easy, however, to forget that Davy’s family was back in Tennessee, and that John Wayne rarely even had a family.

For me, as a grandfather to three girls, the big question as I watched A Hidden Life was: Is one’s spiritual purity worth the suffering of others? I can’t speak for anyone else in the audience, but I was pleading with Franz: Sign the goddamn pledge! Think of your family!

Ultimately, however, along with my grief for them – and for our planet – I was angry at Franz. Yes, you could suggest that my reaction has something to do with my own psychology. But where would that get us? James Hillman said that we have psychology only because we no longer have mythology. To understand what conditioned his decision to refuse the pledge despite knowing the harmful consequences to himself and to his loved ones, we have to look at the history of European religion from a mythological perspective, as I do in Chapters Six and Ten.

For democracy, any man would give his only begotten son. – Dalton Trumbo, Johnny Got His Gun

Roman generals declared, Dulce et Decorum Est Pro Partria Mori, that it was “a sweet and noble thing to die for your country.” This statement may be self-evident to true believers, but for those of us who no longer subscribe to such a belief system, who sit outside the bubble of other people’s myths, we ask: Why would anyone sacrifice his life for his country, or for any other abstract concept such as a religion?

Joseph Campbell taught that Europeans and their American descendants have lived in a “demythologized world” since Christianity began to lose potency in the 12th century. Now, we rarely take notice of the price we pay for living in such a world. Can we even imagine those times when culture and nature together really did hold and protect our ancestors? We live dispirited lives, since we long ago rejected the “spirits” who connected us to this immense and incomprehensible universe. We stand exposed to old, patriarchal conditions – raw opposition between irreconcilable polarities. We still have myths, even if we are rarely aware of them, but they no longer nourish us.

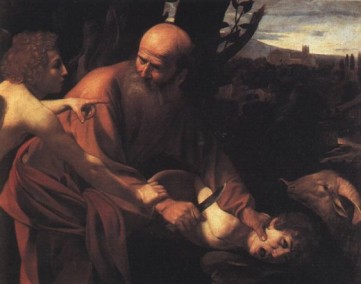

With great respect to Campbell, it seems to me, however, that myth has been breaking down for much, much longer. What remain, exposed like archeological layers, are immensely old stories: the myths of father/son and brother/brother conflict, and the literalization of initiation rites into the brutal socialization of children.  I argue in my book that the willingness of Abraham to sacrifice his son so as to glorify his god is the foundational myth underlying all of western civilization, that the story actually describes the breakdown of symbolic initiation into literal child sacrifice, and that a thousand years later, the death of Christ on the cross solidified this narrative for a new era.

I argue in my book that the willingness of Abraham to sacrifice his son so as to glorify his god is the foundational myth underlying all of western civilization, that the story actually describes the breakdown of symbolic initiation into literal child sacrifice, and that a thousand years later, the death of Christ on the cross solidified this narrative for a new era.

We do not deny some of the great advances in human thinking such as the Alphabet that the Hebrew tradition bequeathed us. But these gifts came with consequences. Well before the Christian era, the Hebrews began to offer something new – history – as a literalization of myth. It was a culture-wide, top-down movement to no longer interpret the old stories as multi-layered social dreams intended to invite everyone to grow their souls, but as literal, chronological truth. Whereas the pagan world had long understood the words of Sallustius (This never happened, but it always is), people throughout the region now heard, This actually happened, and it happened once. It was the first movement from education (to draw something out of young people that already exists in them) to instruction (to stuff pre-determined information into their empty heads).

And we must admit that they also were the first to glorify people who preferred to die rather than change their thinking. Shira Lander writes: “Most scholars consider the Hasmonean traditions preserved in 2 and 4 Maccabees as representing the earliest Jewish strata of martyrology, although there are many earlier examples.”

Maccabees tells of the first martyrs to Roman persecution – not just those who fought, but those who refused to break Jewish law. Sure of going to Heaven, they went uncomplaining to their execution, unknowingly setting an example for future centuries of Christian martyrs:

And when he was at the last gasp, he said, Thou like a fury takest us out of this present life, but the King of the world shall raise us up, who have died for his laws, unto everlasting life.

A century later, the siege of Masada by Roman troops ended in the mass suicide of 960 rebels – or at least this is what Josephus, the sole chronicler of the event, recorded. Since archeologists have disputed his account, we must ask if this literally happened, or whether the evolving narrative of Jewish martyrdom required such a story. It doesn’t really matter, since the area is now one of Israel’s most popular tourist destinations and, more importantly, it shores up the myth of Israeli innocence.

In any event, such narratives began to have enormous emotional resonance, and both Jews and Christians (and later, Moslems) compiled catalogues or lists of martyrs and other saints. Some scholars consider these martyrologies to have been vehicles through which Jews and Christians competed for adherents and negotiated their conflicting claims to ultimate truth. To this day, the faithful venerate their memories, celebrate their feast days, name places of worship, schools and hospitals after them.

Many secular states, we should note, do the same with their war victims regardless of their religious convictions. This is a major way in which nationalism perpetuates itself, saying in effect, they died so that you could live in freedom. You must be willing to do the same. Gervase Phillips writes:

The word martyr itself derives from the Greek for “witness”, originally applied to the apostles who had witnessed Christ’s life and resurrection. Later it was used to describe those who, arrested and on trial, admitted to being Christians. By the middle of the second century, it was granted to those who suffered execution for their faith. Christians were not alone in their admiration of those willing to die for their principles. The philosopher Socrates was unjustly condemned to death in 399 BC for “refusing to recognize the gods”…There was, however, a striking difference between Socrates and those martyred in the arenas. The philosopher hoped for, but was not sure of, an afterlife. The martyr, however, was very certain of an afterlife (and) of salvation and reward in heaven.

In the early centuries of the Christian period, as the age of mythological thinking reached its end, it became more difficult to think in terms of the symbolic processes of initiation and rebirth. And the holy text that emerged out of this period omitted the few metaphors of the sacred Earth that had been allowed into Hebrew scripture. As a result, wrote Paul Shepard, the New Testament is “one of the world’s most antiorganic and antisensuous masterpieces of abstract ideology…”

The zealots who wrested control of the church believed that Christ had literally returned from the dead, and that metaphoric interpretation of his life was unacceptable. Theirs was a religion, write Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy, of “…outer mysteries without the inner mysteries…”

In the late second century, they prohibited women from participating in worship. Soon, schisms developed over fine points of dogma, and rival sects attacked each other in furious jihads, even as the Roman state was still persecuting them. Soon enough, when Christianity became the official state religion, they attacked pagans with the same ferocity.

Here, we can apply some social-psychological insight. Christianity grew up within a heritage and in an atmosphere of violence. Like other traumatized children, it became a perpetrator of abuse, and early on it became obsessed with death.

Absolutely nothing attributed to Jesus in the Gospels suggested anything about his death as a sacrifice. Saint Paul, however, changed Christianity’s central focus from the old mythic image of the birth of the Divine Child to his death; in his vision the Aqedah – the story of the binding of Isaac – was completed only with Jesus’ sacrifice and resurrection. A religion of love devolved into an obsession with suffering. It taught that Christ’s sacrifice had occurred once, not as part of an unending cycle. The western world now understood myth literally, as actual history.

And since the idea of one unrepeatable sacrifice excluded any metaphorical or psychological interpretation of Christ’s death as sacrifice of the ego, it resulted in the suppression of initiation rites. Christians came to believe that Jesus, unlike Dionysus and other earlier gods, had died not as the cycle of creation but as penance for humanity’s bad behavior. This subtle yet significant difference shifted the emphasis from the tragedy of the human condition to the innate sinfulness of human nature. Eventually the initiation of adolescents was transformed into the ritual purification of infants who by their very nature were such threats that it was necessary to protect the community from them.

Having died for the sins of the world, Christ became the ultimate, if willing, scapegoat. Men left society (and women) to defeat their own sinfulness. To this day, the monks of Mount Athos in Greece still refuse to allow the presence of female animals onto their sacred grounds.

Eventually, some of these men even pursued martyrdom. In the late second-century, Arrius Antoninus, proconsul of current-day Turkey, was provoked by “the whole Christians of the province in one united band.” He obliged some of them and then sent the rest away, saying that if they wanted to kill themselves there was plenty of rope available or cliffs they could jump off. Later, Ignatius longed to suffer, “but I do not know whether I am worthy”, and Cyprian imagined the “…flowing blood which quenches the flames and the fires of hell by its glorious gore”.

Martyrdom would eventually evolve into one of the most emotive terms in the English language. It became the highest ethical virtue that every believer must be prepared to emulate, a shared tradition of the Abrahamic religions – in Hebrew, Kiddush Ha-Shem (sanctification of the divine name); in Arabic, shahada (witness). But let’s be very clear about how radical this belief was. Leonard Shlain, in The Alphabet and the Goddess, put this astonishing demand into its proper context:

Until the Christian martyrs, there does not occur anywhere in the recorded history of Mesopotamia, Egypt, Persia, Greece, India or China a single instance in which a substantial segment of the population accepted torture and death rather than forswear their belief in an ethereal concept.

This is the legacy of monotheism. No Buddhist, Hindu, Taoist, Confucian, Pagan or member of any of the thousands of indigenous religious systems before or since could possibly understand this willingness to die – or to slaughter one’s own child – rather than to change one’s mind about an idea, or to even to pretend to do so. Bruce Chilton, in Abraham’s Curse, adds:

Uniquely among the religions of the world, the three that center on Abraham have made the willingness to offer the lives of children – an action they all symbolize with versions of the Aqedah – a central virtue for the faithful as a whole.

And as we all know, the meaning of the word “martyr” gradually changed. Abraham’s knife became a soldier’s sword in Christian iconography. Dying as Christ (around 100 AD) became dying for Christ (500), which became killing for Christ (1000), or for Allah. And a thousand years later, give or take a decade or two, the Western world’s relationship with its deity and its understanding of myth and, yes, its contempt for its own children has produced the ultimate descent into literalism: dying for Allah and simultaneously killing as many innocent non-believers as possible.

The tyrant dies and his rule is over; the martyr dies and his rule begins. – Soren Kierkegaard

This is the logical outcome of the disappearance of mythic consciousness and initiation ritual. For thousands of years, men had symbolically killed the child-nature in their boys to invite their full participation in the adult world. But with the crushing of paganism, a literalized myth (the sacrifice of a child for the glory of his father) came to predominate. It was a very old myth, but now Europe was about to feast on the bodies of its young.

With the inexplicable advance of Islam, however, Christianity confronted a new and immensely powerful Other that questioned its assumptions of universal superiority. The Church responded by distracting its nobles from killing each other and enlisting their energies in crusades of conquest and extermination against the infidels. A new figure emerged: the warrior-monk, pledged to both chastity and eternal warfare. It became glorious to die even in defeat because it would be a martyr’s death.

The Crusades mark the first merger of what I have called the paranoid and predatory (link) imaginations. Pope Urban offered the soldiers both remissions of sin (now, violence was a ticket to paradise) as well as an incentive to martyrdom. The result was a scale of atrocities that still puzzles historians, who, writes Chilton,

…have not factored in the sacrificial dimension of Urban’s appeal. Self-sacrifice, more than self-interest, is the hidden hand guiding this strange and relentless history…Crusading was a license, not only to kill, but also to…indulge other appetites, absolved in advance.

Part Three

Several centuries later, as the Christian myth lost its power and a new myth – nationalism –replaced it, Europe enacted the old stories of the sacrifice of the children on a scale that no one could have previously imagined. Between 1914 and 1918, depending on how we count, some ten thousand young men were machine-gunned, gassed or blasted apart by artillery every single day.  And most of them marched willingly into the sacrificial cauldron. The only difference was that now they did it for the Fatherland, rather than for the Father in the sky, although theologians of all stripes encouraged them.

And most of them marched willingly into the sacrificial cauldron. The only difference was that now they did it for the Fatherland, rather than for the Father in the sky, although theologians of all stripes encouraged them.

Curiously, it was at precisely this moment that the new field of psychology began to speak of the “martyr complex” in terms of what we now commonly understand to be a desire to emphasize, exaggerate and create a negative experience in order to place blame or guilt on another person. But perhaps they were not looking at what was right in front of them, the religious roots of this malady. My etymology dictionary states that this “exaggerated desire for self-sacrifice” first appeared in print 1916. On July first of that year, after a week-long bombardment, several hundred thousand British troops rose out of their trenches at dawn on the Somme River to attack the German trenches. Within two hours, 60,000 of them were casualties, 20,000 of them dead.

This of course is the dark side of Hero mythology. On the other hand, we have countless examples of people who stood against real evil and were willing to sacrifice their lives for the greater good – not necessarily for an abstract concept, even one such as “freedom” – but for actual, living people. Each of us has our own list. Mine would include other Germans who resisted Nazism and the Muslims in that same war who risked everything to protect their Jewish neighbors. My essay Kind of a Circle tells one of those stories.

We all admire American anti-war and Civil rights activists, and we ought to praise our whistleblowers, from Daniel Ellsberg to Ed Snowden, Jeffrey Sterling, John Kiriakou, Reality Winner and Chelsea Manning, and journalists such as Julian Assange for the same reason. Here is Mario Savio’s ‘bodies upon the gears’ speech from 1964.  And even this week, two Oakland mothers who took over an empty house asked for support and hundreds turned out to put their bodies on the line. We all have our lists of those we admire for sticking their necks (or other body parts) out. How about those people who donate kidneys to save a life? The list goes own.

And even this week, two Oakland mothers who took over an empty house asked for support and hundreds turned out to put their bodies on the line. We all have our lists of those we admire for sticking their necks (or other body parts) out. How about those people who donate kidneys to save a life? The list goes own.

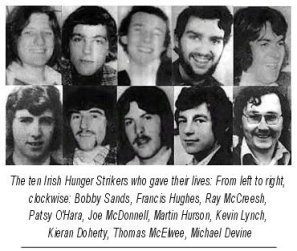

It does get a bit sticky, however, when we consider those throughout the past century who went  on hunger strikes – and many of them died – to force the wider world to pay attention to their causes. Again, some might ask, what did they accomplish? Did anyone notice? Even this week, two asylum seekers in ICE custody have been on hunger strike for over seventy-five days. Have you noticed?

on hunger strikes – and many of them died – to force the wider world to pay attention to their causes. Again, some might ask, what did they accomplish? Did anyone notice? Even this week, two asylum seekers in ICE custody have been on hunger strike for over seventy-five days. Have you noticed?

It gets even stickier when we consider individuals such as the Buddhist monks who immolated themselves to protest South Vietnamese government in the early 1960s, or the Hindu practice of Sati. A Wikipedia article describes this widespread phenomena here.

During the Great Schism of the Russian Church, entire villages of Old Believers burned themselves to death in an act known as “fire baptism”. The example set by self-immolators in the mid 20th century did spark numerous similar acts between 1963 and 1971…Researchers counted almost 100 self-immolations…In 1968 the practice spread to the Soviet bloc…Since 2009, there have been, as of June 2017, 148 confirmed self-immolations by Tibetans, with most of these protests (some 80%) ending in death….A wave of self-immolation suicides occurred in conjunction with the Arab Spring protests in the Middle East and North Africa, with at least 14 recorded incidents.

Sometimes we need to reconsider some of these images.  Father Greg Boyle, the “real Christian” I referred to above, who created Homeboy Industries to put former gang members to work, has reframed the contemporary urban phrase of deep friendship I’d take a bullet for him into Nothing stops a bullet like a job!

Father Greg Boyle, the “real Christian” I referred to above, who created Homeboy Industries to put former gang members to work, has reframed the contemporary urban phrase of deep friendship I’d take a bullet for him into Nothing stops a bullet like a job!

But why do we celebrate and venerate – in thousands of stories and films – one very particular kind of heroism? For context, we have to take another digression, this time into American mythology. And we have to acknowledge that for well over a century, American popular culture, disseminated by Hollywood, has overwhelmed indigenous and local storytelling nearly everywhere to become, for better or for worse, world mythology. While we remember Joseph Campbell’s foundational text, The Hero With A Thousand Faces, we need to understand how the American story completely inverted it. Chapters Seven and Nine of my book address this theme in much greater detail, but here is its essence.

The classic hero enacts the three-part initiation theme found in nearly all cultures. Born in community, he hears a call, ventures forth on his journey and returns, sadder but wiser, with the gifts of insight and knowledge. The community welcomes him home, with the old wisdom that each generation must endure these trials in order to remake culture and keep it fresh.

By contrast, the American hero comes from elsewhere, entering the community only temporarily and only to defend it from malevolent attacks. Its leaders, who are weak, incompetent or corrupt, often betray him. Though he cares about them, he is not one of them.

Often his identity is a secret; he may wear a mask or bizarre costume. He is without flaw but also without depth. He is not re-integrated into society, and in recent versions, the community itself is not fully re-integrated. The Other – Terror – is now a permanent threat. “If the function of the enemy is to represent uncontrollable human desire,” writes James Gibson, “then he must constantly be reincarnated in some form or other.”

Classic heroes often wed beautiful maidens, enact the sacred marriage (hieros gamos) and produce many children. But the American hero (with few exceptions such as James Bond and comic antiheroes) doesn’t get or even want the girl. Even Bond remains a bachelor. Often the hero must choose between an attractive sexual partner and duty to his mission. Some (Batman, the Lone Ranger, etc.) renounce marriage altogether, preferring a male “sidekick.” John Wayne (in almost all of his roles), Hawkeye, the Virginian, Superman, Green Lantern, Spiderman, Rambo, Sam Spade, Indiana Jones, Robert Langdon, John Shaft, Captains Kirk, America and Marvel and dozens of others: all are single. They may be divorced or widowed, but they are all unattached to the feminine principal. In this essentially Christian story, their sexual purity ensures moral infallibility, but it also denies both complexity and the possibility of healing.

Indeed, sexual impurity corrupts Eden. The hero often enacts his savior role in disaster films (Earthquake, Towering Inferno, Tidal Wave, Jaws). In these films, the sexual license of certain (usually female) characters seems to trigger the destruction, and they die first. Nature responds with a moral cleansing. The pattern was set in the Old Testament: only the pure and faithful escape.  The first victim in Jaws (one of cable TV’s most popular re-runs) is a sexually provocative woman. The final scene, in which the hero (who is married but who has refused to make love to his wife) destroys the giant shark, perfectly recreates the 4,000-year-old story of Marduk’s killing of Tiamat. Once again, the hero vanquishes the feminine serpent.

The first victim in Jaws (one of cable TV’s most popular re-runs) is a sexually provocative woman. The final scene, in which the hero (who is married but who has refused to make love to his wife) destroys the giant shark, perfectly recreates the 4,000-year-old story of Marduk’s killing of Tiamat. Once again, the hero vanquishes the feminine serpent.

The classic hero endures the initiatory torments in order to suffer into knowledge and renew the world. This old, pagan and tragic vision recognizes that something must always die for new life to grow, and that this is a symbolic process, not necessarily a literal one. But the American hero cares only to redeem (“buy back”) others. Born in monotheism, he saves Eden by combining elements of the sacrificial Christ who dies for the world and his zealous, jealous, omnipotent father. The community begins and ends in innocence. And though this hero may be willing to sacrifice himself in order to restore innocence to the community, he usually doesn’t actually die. But he does leave when his work is done. Even if his heroism does result in his death, he returns like Christ to “a better place,” his father’s house.

The hero’s superhuman abilities reflect a hope for divine redemption that science has never eradicated. Only in our salvation-obsessed culture and the places our movies go does he appear. Then, he changes the lives of others without transforming them.

I can’t emphasize these insights too strongly. The redemption hero, whom Americans admire above all others, has inherited an immensely long process of abstraction, alienation and splitting of the western psyche. He gives us the model, wrote James Hillman, “for that peculiar process upon which our civilization rests: dissociation.” He is utterly disconnected from relationship with the Other, whom he has demonized into his mirror opposite, the irredeemably evil. Since he never laments the violence employed in destroying such an evil presence, he reinforces our own denial of death. His appeal lies deep below rational thinking.

This hero requires no nurturance, doesn’t grow in wisdom, creates nothing, and teaches only violent resolution of disputes. His renunciation justifies his furious vengeance upon those who cannot control their appetites for power or sex, and this clearly has a modeling effect on millions of adolescent males in each new generation. Defending democracy through fascist means, he also renounces citizenship. He offers, write Jewett and Lawrence, “vigilantism without lawlessness, sexual repression without resultant perversion, and moral infallibility without… intellect.”

His work is too important for the trivial distractions of relationship with real people such as his wife and children because his true allegiance is to the father gods of the sky. Again, the pattern was set two thousand years ago when Jesus returned to his father, leaving the tomb empty. Yes, we admire Franz Jägerstätter as a perfect exemplar of that mythic narrative, as one who died for, perhaps as Christ. But many of us are parents and grandparents. And we all had, even for the briefest of times, a father. Franz went to a better place, but he left his children here.

So – The final scenes of A Hidden Life unfold, the credits role, and we sit in the still-darkened theater weeping. This much is certain. But why are we weeping? I won’t lie: I heard the voice of John Lennon:

Mama don’t go!

Daddy come home!

Mama don’t go!

Daddy come home!

Is this old, irrelevant stuff? Shira Lander describes an adult study session she conducted at a synagogue on the subject of martyrdom. She asked the participants how the subject made people feel.

Most were unsettled by the images, and even were repulsed by the idea of martyrdom—all except the rabbi, who declared with confidence, “I think I would have to choose martyrdom if faced with apostasy. How could I fulfill my role as a model of faith for my community if I didn’t? That’s part of being a rabbi.”

Part Four

Believe those who are seeking the truth. Doubt those who find it. – Andre Gide

Slowly I would get to pen and paper, make my poems for others unseen and unborn. – Muriel Rukeyser

I don’t like to say this, but I have to admit that pretty much everything is more complicated than it seems. There are so many ways to look at anything. They are all valid, and perhaps we need them all. As historians we have to be literal, and so we ask, what actually happened? As psychologists we are concerned with relationships (internal or external), so we ask, why did it happen? Could it have happened differently? James Hillman insisted on a polytheistic psychology that can reflect the polytheistic nature of our souls and the fact that we are all multiple personalities. So as mythologists we ask where am I – right now – in this story that constantly repeats itself? What part of it – what specific image – is roiling my emotions right now?

Do we admire Franz Jägerstätter’s self-sacrifice? Depending on our perspective – that is to say, depending perhaps on the emotional issues that drive us – we may well observe that he was sacrificing more – much more – than his own life, and we will react accordingly. Regardless, if we pay attention to how our own souls move, we realize that A Hidden Life, like any great work of art, has thrown us into an emotional turmoil that can only be resolved not with answers but with more questions.

Questions like: Who am I? By what circles of relationship do I define myself? What would I do for a cause, for an abstract ideal? For what reason – or which people – would I lay down my own life? For what cause or which people would I step into the fire of sacrifice, aware that my act might well be an utter waste? Do I have any faith that such an act might well have impact on others unknown and even unborn?

Or: What part of my own consciousness, what belief systems, what identity have I yet to sacrifice in order to die into a greater self, the self that my ancestors have been waiting for me to manifest? Why exactly have I entered this world? What unperformed sacrifices would I regret if I were to die today?

We are right where we need to be – in the realm of profound mysteries, where as physicist Niels Bohr wrote,

The opposite of a correct statement is a false statement. But the opposite of a profound truth may well be another profound truth.

As I mentioned above, no member of any of the thousands of indigenous religious systems that existed prior to the advent of monotheism could ever support this willingness to sacrifice one’s body for an idea – to literally, physically die. Of course, I can’t prove such a statement, but everything I’ve ever read or learned from living representatives of such cultures reinforces it. And here is another level of mystery: much of these oldest wisdom in the world coincides with the 20th-century insights of Archetypal Psychology. I remember a scene at a men’s conference about 25 years ago. Malidoma Somé spoke at length about the traditions of his Dagara people, especially in terms of the symbolic death of the childlike or heroic ego that is necessary during initiation. When he finished, Hillman rose to say, “This is exactly what I have been trying to say for years!”

In these times when this beautiful world is in such terrible danger, we all need to grow – to remember what we all once knew – the capacity to think mythologically. Then, as I write in Chapter One of my book,

…We perceive meaning on several levels simultaneously, aware that the literal, psychological and symbolic dimensions of reality complement and interpenetrate each other to make a greater whole…There is no reason to assume that indigenous people cannot do this. Actually, it is we who have, by and large, lost this capacity. The curses of modernity – alienation, environmental collapse, totalitarianism, consumerism, addiction and world war – are the results…

For tribal people, to explain is not a matter of presenting literal facts, but to tell a story, which is judged, writes David Abram, by “whether it makes sense… to enliven the senses” to multiple levels of meaning…and myth is truth precisely because it refuses to reduce the world to one single perspective.

So in a sense we are back where we started. Of course, self-sacrifice amounts to nothing more than suicide – on one level.

And again, we must take note of the synchronicities. I mentioned above that the Gestapo executed Otto and Elise Hampel on April 4th, 1943 (another source says they died on the 8th). That same week, Franz was nearby, in another Berlin prison. On the 2nd of the month, Bulgaria informed the Germans that its 25,000 Jews would not be turned over to German control. On the 5th, the Gestapo arrested war resister and Lutheran Pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer (he was executed shortly before the end of the war). On the 9th, the S.S. murdered 2,300 Jews in the Ukrainian Ghetto of Zbrow.

Fred Korematsu’s court appeal was pending. In Budapest, Oskar Schindler was in contact with the Jewish resistance. On the 17th, Hungary refused (temporarily, it turned out) to deliver its 800,000 Jews to the Germans. On the 19th, the Gestapo executed fourteen Germans associated with the White Rose anti-Nazi resistance (in February they had showered the atrium of Munich University with anti-Nazi leaflets). On the same day, the Belgian resistance liberated 233 Jews from an Auschwitz-bound train. On the 19th, the Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto began their famous uprising.

Were the sacrificial acts of the Hampels and Franz Jägerstätter emblematic of a great turning point in the war? Is it possible that their deaths did not occur in a moral vacuum? Speaking of turning points, biochemist Albert Hofmann accidentally ingested LSD for the first time on April 16th, 1943.

This quote from George Elliot appears in the last frame of A Hidden Life:

…for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.