In September of 2020, with the pandemic, the economy, the racial violence, the election (see my essay, “A Mythologist Looks at the 2020 Election”) and (for Californians) the forest fires on our minds, it’s easy for us to shunt thoughts of America’s post-World War Two foreign policy to the back of our minds. But when we bring them to the forefront, we remember some of the statistics that remind us of the astonishing and heartbreaking seventy-five years of waste and cruelty, including the bombing of some forty countries.

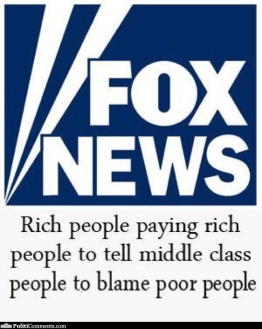

Now, and for several decades, the U.S. military budget has amounted to two-thirds of the nation’s discretionary budget. It is half the world’s budget, greater than the next ten countries combined.

Such estimates, by the way, are very conservative. When all aspects of military spending are added in, including the Department of Energy’s nuclear-weapons programs, the Departments of State, Veterans Affairs and Homeland Security, various anti-terrorism programs, foreign military assistance (most of which goes to Israel and Egypt) and interest paid on the national debt (much of which pays for past wars), the true cost of the American empire, supported equally by Democrats and republicans, is well over a trillion dollars per year.

And we may well be forced to conclude that much of our domestic political drama is really a distraction from this much larger moral tragedy.

And when either presidential candidate dismisses Medicare For All, even during this pandemic, with “Nice idea, but how are you going to pay for it?” he is quite deliberately avoiding this elephant in the living room, and assuming that the mainstream media will as well.

Our beliefs about wealth and poverty are the absolute foundations of our domestic issues. But the same thinking has undergirded our foreign policies – and the public’s acquiescence to them – since the very beginning. This is how white Americans have always resolved the contradiction of living in a society that raises freedom and equality to the highest values while simultaneously enslaving millions, murdering other millions and consuming vast areas of the Earth and its resources. From the Indian wars and the Mexican War to Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, to whatever “October surprise” madness Trumpus may be planning before the election, it has always been composed of a series of seven basic principles:

1 – We are good, pure and innocent, and we always come to help those in need.

2 – We become violent only when we are provoked, or to defend freedom.

3 – We hurt / kill / enslave / take the resources of other people or nations.

4 – We can only do this if they were evil. They, the victims, are to blame.

5 – Therefore, they must have acted or planned to attack us. We are the actual victims.

6 – Therefore, we are justified in having attacked them, and we are not accountable.

7 – Ultimately, we do it for their own good.

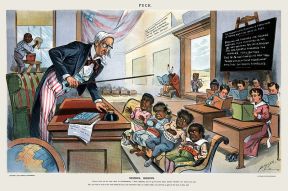

Chapters Seven and Eight of my book explain how the mythic narratives grew about a people without land who settled a “land without people” in the name of freedom, and how a nation of radical individualists became a nation with a unified, divine mandate. Since those times, Americans have been “coming to help” in countless places – whether asked or not. And always, as the missionaries to Hawaii were described, many of those who came to do good ended up doing quite well for themselves. This is the particularly American genesis of empire.

Skeptics will argue that in this regard America empire is not exceptional. Indeed, apologists for other empires such as the British have often strayed into this territory. The Nazis claimed that Poland had provoked them into defending themselves (by invading Poland). Chroniclers of the medieval Crusades justified their pillaging of Muslim lands (and raping of Jewish communities on the way) with talk of divine motivation. But such language fell most easily upon white, Anglo-Saxon American ears because by the second half of the 19th century, we already had a 200-year legacy of believing in our good intentions.

At that time, American intellectuals (and only in America) twisted the idea of natural selection into “Social Darwinism” by falling back upon Puritan justifications for wealth and poverty and asserting that America’s wealth, just like the wealth of its ruling classes, proved its virtue.

Exploitation and elimination of the weak, they claimed, were natural processes; and competition produced the survival of the fittest. The next step was to infer that only the affluent were worthy of survival. These gatekeepers were, of course, merely restating the Calvinist view of poverty as a condition of the spirit. Life was a harsh, unsatisfying prelude to the afterlife, redeemable only through discipline. Deeply religious and idealistic people passionately argued that the suffering of the poor was a good thing because it provoked remorse and repentance, and that political movements to relieve their condition were unnatural. Secular apologists, meanwhile, simply substituted the word “nature” for “God.”

Social Darwinism was one of the primary justifications for colonialism, at least among Americans. The intense and unrelenting competition for survival had produced a new human type, the Anglo-Saxon, who alone had the moral sense to accept the White Man’s burden.  Such men were uniquely qualified to help civilize those who couldn’t improve themselves without the prolonged tutelage of enlightened colonial rule. For a detailed description of how generations of white American intellectuals have justified this nonsense, see The History of White People, by Nell Irvin Painter. These notions, tempered with superficially idealistic verbiage, have remained at the core of America’s foreign policy right up to the present, because they express the essence of our mythic narratives.

Such men were uniquely qualified to help civilize those who couldn’t improve themselves without the prolonged tutelage of enlightened colonial rule. For a detailed description of how generations of white American intellectuals have justified this nonsense, see The History of White People, by Nell Irvin Painter. These notions, tempered with superficially idealistic verbiage, have remained at the core of America’s foreign policy right up to the present, because they express the essence of our mythic narratives.

When some future American President decides that it will be in his political interests to invade Venezuela, he will justify his criminal actions by resorting to this essentially mythological language. As Noam Chomsky has said, “If the Nuremberg laws were applied, then every post-war American president would have been hanged.”

But Social Darwinism evokes a profound anxiety that mirrors the anxiety at the very core of Puritanism: how can I really know if I am among the elect? If the Other actually has the same rights, skills and privileges that I have and the Other is evil, what does that make me? It should be no surprise that the issues of gay marriage and immigration, not to mention equal rights for Black people, have provoked such vicious reactions in our time.

When social change periodically creates threats to our sense of identity, as it did after the Civil War and during each of our regular economic crises, white Americans typically coalesce around our most core principles and attitudes. We fall back upon the tried-and-true notions of knowing who we, as we would like to think of ourselves, but negatively: in terms of the Other. We are not the Other.

But the unapologetic rants about entitlement and poverty of charlatans such as Jerry Falwell and clowns like Herman Cain (both quoted in Part One of this essay) seem somewhat new, or at least since the political backlash that brought Ronald Reagan to power 35 years ago. Why does the media now give them such attention? Perhaps only because the public’s disgust with Trumpus is forcing them to do so.

Demonization of the poor continued unabated in the 2016 election and beyond. Alice Miranda Ollstein writes of Paul Ryan’s rhetoric:

For several years — as he has pushed policies to slash Medicaid funding, food stamps, unemployment insurance, and other social programs — Ryan has repeatedly referred to poverty as a “culture problem” among people in “inner cities,” where “generations of men [are] not even thinking about working.”…His most recent poverty plan takes a punitive stance, punishing people who can’t find a job by a certain mandated deadline by reducing their benefits.

When old myths break down, writes historian Richard Slotkin, ideology generates “a new narrative or myth…to create the basis for a new cultural consensus.” Or we could say that (with the help of the corporate media) older, previously de-legitimated narratives resurface into the public discourse because they still retain their emotional attraction, and because white men need, with increasing desperation, something to confirm their sense of identity.

We have been seeing a resurgence of this “blame the victims” rhetoric because the shared consensus that upheld our social fabric of optimism, perpetual growth, technology, white privilege and imperial influence began to collapse during the 1960s. Or, as I have written, cracks have appeared and continued to widen in the great edifice of the myth of American innocence. These cracks have brought into question most of the assumptions that Americans – certainly most white male Americans – have lived by and continue to identify themselves by. And at some deep level, we all know that if any one of those assumptions is called into question, then the whole house of cards may collapse. If it does, we know that it will reveal the vast pit of self-hatred, anxiety and grief that lies just below consciousness, that we normally avoid thinking about with our optimism, our consumerism, our addictions, our fundamentalism – and our race hatred.

It’s very difficult to determine how many people of color we kill, writes Michael Harriot:

The reason the number remains a mystery is that law enforcement agencies, politicians, lobbyists and the…NRA have gone to extraordinary measures to prevent government agencies from counting how many people die at the hands of law enforcement agencies. Even when organizations attempt to count the number of people who die in police encounters, the data is sometimes flawed and often incomplete…In 2014, for the first time in history, the Obama administration tasked the FBI with counting how many arrest-related deaths happened that year. When the Bureau of Justice Statistics issued its report, it found that the FBI had been under-reporting the number by an average of 545 deaths per year.

The estimates range from the Washington Post’s preposterous and insulting statement that “police fatally shot 13 unarmed Black men in 2019” to multiple sources which agree that cops, jailers and vigilantes kill well over a thousand people per year (or three per day), over half of whom are POCs and about 20% of whom are unarmed.

And this creates a profound anxiety, an anxiety that mirrors that at the very core of Puritanism: how can I really know if I am among the elect? If the Other actually has the same rights, skills and privileges that I have and the Other is evil, what does that make me? It should be no surprise that the issues of gay marriage and immigration have provoked such vicious reactions in our time.

America is really good at this, because our mythic narratives, our electronic entertainment, our politicians and our preachers have consistently told us not only that bad guys get what they deserve, but also that if people – at least POC – get the punishment that they deserve, then they must be bad.

Even through the Reagan years and beyond, white rage had been restrained, at least in political rhetoric, if not in policy and police behavior, despite the constant fear-mongering. For Terrorist Fearmongers, It’s Always the Scariest Time Ever

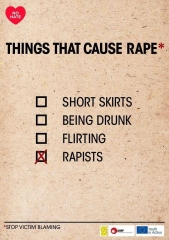

But Trumpus gauged the new rise of white victimhood and rode it to power not only by evoking fear of POCs and Muslims, but also by using previously unacceptable language to even blame victims of mass shootings and rape survivors for their own misery.

…if the attack on Dr. (Christine Blasey) Ford was as bad as she says, charges would have been immediately filed with local Law Enforcement… – Trumpus

The President’s words have enabled white supremacists across the country – especially among the police and right-wing vigilantes – to justify their undiluted violence, where the vilest of the victim-blaming is reserved for POCs, most especially those whom they have murdered. From well before Trayvon Martin to beyond Jacob Blake (there have already been others), prosecutors, defense attorneys, judges and right-wing media habitually justify the fate of a police shooting by dredging up negative details about his or her life prior to the incident.

“You are using his past to determine whether the officers were right?” Quinyetta McMillon, the mother of Alton Sterling…said in a recent interview. “This has nothing to do with why he was gunned down.”

But in the minds of mythologcally-instructed, 21st century Calvinists, such material, real or not, has everything to do with why cops pull triggers. And as this president’s popularity continues to drop in the polls, we really shouldn’t be surprised even this week to read sickening headlines such as Kenosha Police Chief Blames Protesters for Their Own Deaths, Defends Vigilante Groups or First Man Shot By Kyle Rittenhouse In Kenosha Riot Was A Convicted Pedophile (to be clear, I’ve only seen this accusation in far-right websites, and to be even more clear, it doesn’t freaking matter if it is true).

Expect more of this as November approaches. The myth – and Trumpus’ re-election hopes depend on it. This is the American story and the American psyche. But not every American, not those whose mythologies come from this North American earth.

Representatives of indigenous cultures do not need courses in Depth Psychology to know how fragile such a personality is. If we regard ourselves from their perspective, we may well realize that America is a society primarily composed of – and led by – uninitiated men. At the root of our national identity is the grief and rage of young men who have never been seen and blessed by their elders, who cover up their depression with masks of grandiosity, racial entitlement and easy violence.

We white people insist that we are not the Other, and that we are good, pure and innocent. So whatever happens to the Other, whatever we inflict upon her, must be her own fault. But in our souls, we know very well that this is a 400-year-old projection, and that it really speaks of our own self-image.

Perhaps the greatest tragedy of the whole American project is that, well below the surface of our egalitarian ideals, our optimism, our heroic and macho posturing and our good intentions, most of us still believe this about ourselves.