Part One

Their strictly Puritanical origin, their exclusively commercial habits, even the country they inhabit, which seems to divert their minds from the pursuit of science, literature, and the arts…a thousand special causes…have singularly concurred to fix the mind of the American upon purely practical objects. – Alexis De Tocqueville

More than any other people on Earth, we bear burdens and accept risks unprecedented in their size and their duration, not for ourselves alone but for all who wish to be free. – John F. Kennedy

All modern people have long internalized and taken for granted the 5,000-year-old heritage of patriarchy, as well as the 3,000-year-old literalized thinking of the Judeo-Christian tradition. We live in what Joseph Campbell called a “de-mythologized world.” It is not that we no longer have myths, but that we are generally unaware of them, they no longer serve us, and our ignorance of them makes us dangerous.

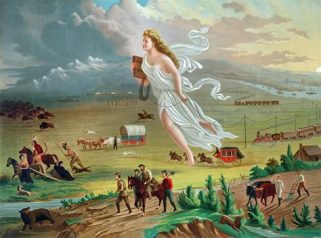

Within the wider concentric circles of those older myths, by adolescence almost all white Americans incorporate the myth of innocence. Our educational, religious and political institutions still teach the values of individualism, consumerism, mobility, racist exclusion and competition – and underneath, the deeper legacy of Puritanism – that define us as Americans. Above all, the media have replaced priests and storytellers in the ancient function of telling us who we are: a nation without a shadow, existing to enlighten and redeem the world – if necessarily, through violence.

Our essence, they tell us, is free enterprise. Entering the world as blank slates, with neither baggage nor purpose, we are free to make our own destiny, on our own merits. We assume that everyone should – and does – have equal access to the resources needed to become anything they want to be, and that one’s responsibilities to the broader community are limited to its defense.

And when sceptics confront us with statistics or stories that question these assumptions, it is our characteristic shock, followed by denial and forgetting, that is the proof of the power of myth.

Myths speak of beginnings, how the world came into existence. We take for granted that the gods (or in our story, the forefathers, the founding fathers) have left us the means to aid the process of freely competing with each other, including a free market of ideas, products and services.  As a result, we believe that we live in an affluent society – the best in the world – that has resolved old racial problems, and that we were meant to do this. Again: our shocked response to regular evidence to the contrary shows how strongly our mythic narratives hold us.

As a result, we believe that we live in an affluent society – the best in the world – that has resolved old racial problems, and that we were meant to do this. Again: our shocked response to regular evidence to the contrary shows how strongly our mythic narratives hold us.

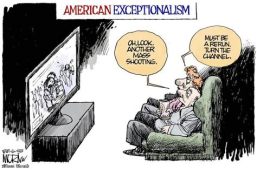

The idea of American exceptionalism arises out of this contradictory tangle of ideals and realities.

Curiously, this collectivity of free and purposeless libertarians thinks of ourselves as a nation that is inherently different from other nations; that we are in fact superior to other nations; that we have a unique mission to transform the world, to spread opportunity and freedom everywhere.

However, anyone who has achieved some detachment from the myth can see that those rights and freedoms have rarely been available to most citizens. Indeed, Americans have won them only after decades of sacrifice; and many of them have been eroded in recent decades. But the fact remains that the myth of national purpose and innocence is so pervasive that even in those rare moments when the nation confronts bare reality, we quickly re-veil it. Recall the conservative refrain of the 1960’s: My country – right or wrong! Americans have developed a very old, unique and massive cognitive dissonance – if facts contradict the story, then it is the facts that must change.

Our academic and media intellectuals continually reframe information. This is not at all to take a conservative (more accurately, reactionary) position on the mainstream media as “fake news,” only to acknowledge how they set the terms of debate, frame all reporting in subtle but consistent ways, and rarely convey news or commentary that might be perceived as inconsistent with the main story. In other words, the “liberal establishment” has an essentially religious function, like the Inquisition: preventing, or at least marginalizing heresy. For more on this theme, please see these other essays of mine:

Funny Guys, Fake News and Gatekeepers

Americans really are unique in many ways, concluded historian Richard Hofstadter. Whereas other nations’ identities come from common ancestry, “It has been our fate…not to have ideologies, but to be one.” One cannot become un-English or un-French. “Being an American…” wrote Seymour Lipset, is “an ideological commitment. It is not a matter of birth. Those who reject American values are (considered to be) un-American.”

It is an eternal mystery: the world’s most materialistic culture, where consumerism and “lifestyles” were invented, where the predatory imagination has reached its apogee – is also the most religious country in Christendom, exhibiting greater acceptance of literal belief and higher levels of church attendance than other industrialized countries. Ninety-four percent of Americans express “faith in God,” as compared with 70% of Britons. Only 2% of Americans are atheists, as opposed to 19% in France.

Part Two

I’ve always believed that this blessed land was set apart in a special way. In my mind it was a tall, proud city built on rocks stronger than oceans, wind-swept, God-blessed, and teeming with people of all kinds living in harmony and peace. – Ronald Reagan

What I really found unspeakable about the man (Reagan) was his contempt, his brutal contempt, for the poor. – James Baldwin

I will never apologize for the United States of America. I don’t care what the facts are. – George H. W. Bush

Here is another curious contradiction. This is the nation that took radical individualism to extremes seen nowhere else. The United States is the only major nation with significant Libertarian ideologues (for more, see my article The Mythic Foundations of Libertarianism), even if most of them prove to be confused if not hypocritical. And yet, studies show that Americans are more willing to fight if their country goes to war.

This stems not only from our violent heritage and historical isolation from war’s effects, but also from our Protestant moralism and the myth of the Frontier. A majority of us tell pollsters that God is the moral guiding force of American democracy. Therefore, when Americans go to war, they generally define themselves as being on God’s side against evil incarnate. Wars are not simple political conflicts; they are crusades, and evil must be annihilated. Lipset writes, “We have always fought the ‘evil empire.’”

Americans have a high sense of personal responsibility and independent initiative. Shared belief in the value of hard work, public education and equality of opportunity continues to influence attitudes toward progress. In 1991, close to three fourths of parents expected their offspring to do better than they, and (in 1996) a similar percentage expected to improve their standard of living, while only 40% of Europeans shared this optimism. Forty percent believed that there is a greater chance to move up from one social class to another than thirty years before. We still believe – deeply – in a nation of “self-made men” – and that poverty is our own fault, not that of the system. We still believe that we will continue to grow and progress toward fulfillment of our dreams, despite consistent evidence to the contrary.

But what are those dreams? Aren’t they equal part nightmare? For all of its enviably optimistic, pragmatic, “can-do” ways, from the beginning this nation has always carried a great bag of fear over its shoulder. At the root of things was a kind of theological fear: the constant anxiety of never really knowing if one is among the elect of God, which propelled the Puritan to work unceasingly.

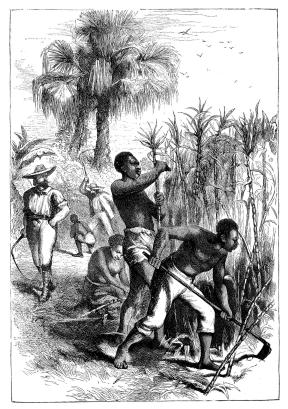

Layered above that has been the unsettling dread of the guilty, colonial settler: the knowledge that one will never belong to this land as one’s Old World ancestors did to their land. These anxieties, and the need to justify the theft of a continent and the enslavement of millions, led to the creation of the myth of American innocence. And this myth required a people who would perpetually live in fear of the unspeakably evil red men who might sweep down out of the forest at any moment to attack the innocent community, and of treacherous black men who might rise up from within the community to mix with their women.

These anxieties, and the need to justify the theft of a continent and the enslavement of millions, led to the creation of the myth of American innocence. And this myth required a people who would perpetually live in fear of the unspeakably evil red men who might sweep down out of the forest at any moment to attack the innocent community, and of treacherous black men who might rise up from within the community to mix with their women.

Lipset reveals the characteristically liberal naiveté of our intellectual classes: “America has been a universalistic culture, slavery and the black situation apart” (my italics). Indeed.

Human bondage, institutionalized discrimination, mass murder of the natives and “free” land created the economic foundations for the very senses of optimism, moralism, affluence and idealism that, to Lipset, distinguish America from other countries.  Howard Zinn provides some needed balance: “There is not a country in world history in which racism has been more important, for so long a time, as the United States.” Without the protracted, unresolved and unmourned crimes of genocide and slavery there would be no affluence, no optimism, no police brutality and no innocence in America. And no privilege.

Howard Zinn provides some needed balance: “There is not a country in world history in which racism has been more important, for so long a time, as the United States.” Without the protracted, unresolved and unmourned crimes of genocide and slavery there would be no affluence, no optimism, no police brutality and no innocence in America. And no privilege.

Whoever uses statistics to argue about America is lost in a dream. Since most polls question likely voters, they ignore most poor people, most minorities and most young people. But this confusion provides us with a metaphor for one of the mythic factors in American exceptionalism: “white thinking.” The sense of privilege is so deeply engrained, so invisible that few whites notice or question it; this is why it has mythic power. Politicians and pundits take the perspective of the white male, speaking of “African-Americans,” or “Asian-Americans,” but never “European-Americans.” Their language reveals exactly who is a member of the polis and who isn’t. This inconsequential example points, however, to the significant.

We must begin with the most fundamental aspect of privilege: it is invisible to nearly all whites, and perfectly obvious to all people of color. It is the psychological advantage of having views that define the norm for everyone else. It allows one to view oneself as an individual. It allows liberals to claim that they don’t think of themselves as any color at all. Tim Wise writes, “To even say that our group status is irrelevant…is to suggest that one has enjoyed the privilege of experiencing the world that way (or rather, believing that one has.)”

Privilege allows working-class whites to deny that privilege itself does not exist. It allows them to vote against their economic interests in favor of other advantages. It allows them, even when dirt-poor, to cleave to an identity of white, male, Christian and heterosexual – as moral and clean – rather than as members of a socio-economic class. It allows them membership in the polis, even if they can’t afford to live within its walls.

White privilege allows one to not have to think about race every day. It is freedom to not be viewed as violent or hyper-sexual, not be racially profiled, not worry about being viewed with suspicion when buying a home, or not be denied a job interview. It is the freedom to avoid being stigmatized by the actions of others with the same skin color, and thus to regularly disprove negative stereotypes.

The invisible ocean of privilege lies at the core of both capitalism and innocence. Despite the grinding tensions and anxieties of modern life, it allows whites – including recent immigrants – to have a sense of place in the social hierarchy and to believe in upward mobility for their children. They can know who they are because, as un-hyphenated Americans, they are not the Other.

For much more, please see these essays of mine:

Old World nations, for all their limitations on freedom, have known who they are because they have inhabited their land forever. But Americans, in the rush to define ourselves in terms of the Other have periodically been overwhelmed by the need to cleanse the polis through the violent rejection of the impure. Without our characteristically American Paranoid Imagination, we would not endure periodic inquisitions and tribunals running from the Salem witch craze through the Red Scare of 1919 through McCarthyism, the post-9-11 anxieties that keep the “war on terror” going, the Tea Party, and Trump.

Here is another surprising contradiction. Because American identity is so fragile, we have always been driven, more than anything, by fear. In 2015, Glenn Greenwald offered some recent quotes by politicians who have made their careers manipulating what is in fact our exceptional willingness to be immobilized by phobias and nightmares:

— Lindsey Graham: We have never seen more threats against our nation and its citizens than we do today.

— Dianne Feinstein: I have never seen a time of greater potential danger than right now.

— NSA chief Michael Rogers: The number of threats has never been greater.

— Canadian defense minister Jason Kenney: The threat of terrorism has never been greater.

— CIA Deputy Director Michael Morrell: The ‘lone wolf’ terrorist threat to the United States has never been greater.

— U.K. Prime Minister Cameron: Britain faces the greatest and deepest terror threat in the country’s history.

— Rep. Mike McCaul: Something will detonate…I’ve never seen a greater threat in my lifetime.

— Anonymous EU counter-terrorism official: The threat of attacks has never been greater — not at the time of 9/11, not after the war in Iraq — never.

“Here we are,” continued Greenwald,

…14 years after 9/11, and it’s still always the worst threat ever in all of history, never been greater. If we always face the greatest threat ever, then one of two things is true: 1) fearmongers serially exaggerate the threat for self-interested reasons, or 2) they’re telling the truth — the threat is always getting more severe, year after year — which might mean we should evaluate the wisdom of “terrorism” policies that constantly make the problem worse. Whatever else is true, the people who should have the least credibility on the planet are the Lindsey Grahams and Dianne Feinsteins who have spent the last 15 years exploiting the terror threat in order to terrorize the American population into doing what they want.

Here are some other essays of mine on this subject:

The Mythic Sources of White Rage

Why Are Americans So Freaking Crazy?

Part Three

America remains the indispensable nation…there are times when America, and only America, can make a difference between war and peace, between freedom and repression. – Bill Clinton

I laughed to myself…”Here we go. I’m starting a war under false pretenses.” – Admiral James Stockdale, on the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incident

These innocent people are trapped in a history they do not understand, and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it. – James Baldwin

It is another colossal mystery, if not an outright contradiction. For the American economic and military empire to justify a constant state of war, with military bases in 160 countries, it has to do two things. It must rely on certain subsets of the exceptionalism myth.

Michael Ignatieff calls them “exemptionalism” (supporting treaties as long as U.S. citizens are exempt from them); “double standards” (criticizing “others for not heeding the findings of international human rights bodies, but ignoring what these organizations say of the United States”); and “legal isolationism” (the tendency of U.S. judges to ignore other jurisdictions). But such policies – absolutely the same under Democratic or Republican Presidents – rely, in turn, on both the belligerence and the ignorance of the public.

And it must rely on keeping its citizens – us – in a perpetual state of anxiety. If we were honest, we’d have to admit that our neurotic susceptibility to fear-mongering is a primary characteristic of American exceptionalism. Here are some others:

America is simultaneously the world’s most religious, patriotic – and materialistic – society. If we add that it is also the most racist, violent, punitive and aggressive of nations, we have the ingredients that require a myth of exceptional innocence. I offer the following statistics and comparisons not out of gratuitous America-bashing, but to put the yawning gap between myth and reality into a helpful perspective. These are a small sample of statistics I collected in 2008 for Chapter Nine of my book Madness at the Gates of the City: The Myth of American Innocence. Some point toward our profound, media-nourished ignorance; others reflect the fundamental themes that really do distinguish America from other societies.

Seymour Lipset’s innocent fascination with the bright side allows him to avoid the fact that America (with the sole exception, for a few years, of Nazi Germany) is the most violent society in history. Most of the realities that actually make America unique stem from the foundational facts of conquest and racism.

Our frontier mythology, individualism and inflated fear of the Other have prevented the gun-control measures common in almost all countries. Americans own 250 million legal and 25 million illegal firearms, approximately 1.7 guns per adult. Forty percent own guns. Our adult murder rate is seven times higher and our teen murder rate twelve times higher than in Britain, France, Italy, Australia, Canada and Germany. These nations together have 20 million teenagers; in 1990 a total of 300 were murdered. That same year, of America’s 17 million teens, 3,000 were murdered, while thirty of Japan’s ten million teens were murdered, a rate one-fiftieth of ours.

Annually, 15,000 Americans are murdered, 18,000 commit suicide and 1,500 die accidentally by guns. Twenty-four percent of us believe that it is acceptable to use violence to get what we want. Forty-two percent strongly agree that “under some conditions, war is necessary to obtain justice,” compared with just 11% of Europeans. In 2020 I hope that I don’t need to provide any statistics on the prevalence of police violence toward people of color, or of mass murders. But I will remind the reader that the vast majority of them are perpetrated by white men.

Our disdain for authority and love of guns contributes to the highest crime rate in the developed world. How we calculate the numbers, of course, reveals our prejudices toward “blue-collar” crime and the lack of political will to control “white-collar” crime, which is certainly far more influential. And there is a mythical component as well. Our fascination with TV and movie Mafioso indicates that many of us perceive organized crime to be an alternative mode of accessing the American Dream. Sociologist Daniel Bell writes that we see this kind of crime as a “natural by-product of American culture…one of the queer ladders of social mobility…”

But the fear of crime and the need for scapegoats results in over two million Americans in jail, more than in any other country except China, with five times the population. With 5% of the world’s population, the U.S. has 22% of the world’s prisoners. And the fact that few of our prisoners and ex-prisoners are allowed to vote is a major factor in the legalized voter suppression that keeps reactionaries in power in over two dozen states. For more on this, see my essay on the election of 2016, Trump: Madness, Machines, Migrations and Mythology.

Traditionally, the fear of crime has also been bound up with the fear of miscegenation, or the mixing of the tainted blood of Black people and other undesirables with that of the pure, Anglo-Saxon blood of Whites, who first began calling themselves “native Americans” as early as the 1830s. Well before that point, the nation that was truly exceptional in the sense of being composed primarily of immigrants and their descendants had already been struggling with both legal and de facto definitions of just who would be accepted as full citizens. And this has never ended. The topic is too vast for this essay, but you can read much more here:

The United States has over a million lawyers, far more both in sheer numbers and per capita (twice as many as Britain, in second place) than the rest of the world. This in part reflects the fact that we have far higher rates of divorce and single parent families. But our teen pregnancy rate – twice that of any European nation – leads to questions of religion. American teenagers’ expressive individualism leads them to have early intercourse. But often their greater religiosity – and restricted access to sex education – undermines any attempts at a rational approach to birth control.

Despite the creed of separation of church and state, the Republican base continues to insist on the old, strict legislation of morality. While abortion and gay rights are non-issues in almost all European countries, puritan prejudices continue to infect our attitudes toward the body. Although we engage in more premarital sex than the British, we are far more likely to condemn promiscuity. One out of every four American men condemn premarital sex as “always wrong” – more than three times that of the British.

Between 45% and 60% tell pollsters that they believe in the literal, seven-day creation story, and 25% want it required teaching in public schools. Forty percent believe the world will end with the battle of Armageddon. Sixty-eight percent (including fifty-five percent of those with post-graduate degrees) believe in the literal existence of the Devil.

Part Four

Like generations before us, we have a calling from beyond the stars to stand for freedom. This is the everlasting dream of America. – George W. Bush

I believe in American exceptionalism with every fiber of my being. – Barack Obama

In fact, American exceptionalism is that we are exceptionally backward in about fifteen different categories, from education to infrastructure. – James Hillman

And yet, despite such emotionally laden issues, both civic participation and civic awareness continue to decline. Americans vote in lower percentages than in any other democracy. One hundred million eligible voters stayed home in November of 2016. Of those ineligible to vote, 4.7 million – a third of them Black men – are disenfranchised by felony convictions.

America has slipped from first to 17th in the world in high school graduation rates and 49th in literacy. Surveys regularly indicate just how “dumbed-down” we are: 60%, for example, know that Superman came from the planet Krypton, while 37% know that Mercury is the planet closest to our sun. Similarly, 74% know all three Stooges, while 42% can name the three branches of the U.S. government.

Millions of citizens completely misunderstand common political labels. Nearly 50% believe or are not sure that conservatives support gun control and affirmative action, and 19% think that conservatives oppose cutting taxes. Seventy percent cannot name their senators or their congressman. In 2000, twelve million Americans thought that George W. Bush was a liberal.

Studies indicate that social mobility – the opportunity to move up into a higher social class – has decreased significantly. But in a 2003 poll on the Bush tax plan, 56% of the blue-collar men who correctly perceived it as favoring the rich still supported it. The myth of the self-made man is so deeply engrained that our ignorance of the facts is equaled only by our optimism: in 2000 19% of respondents believed that they would “soon” be in the top one percent income bracket, and another 19% thought that they already were. Similarly, 50% think that most families have to pay the estate tax (only two percent do), and two-thirds think that they will one day have to pay it. Twenty years later, those numbers have certainly come down. But in America disillusionment can just as easily turn someone’s politics to right as to the left, as the 2016 election showed.

Our ignorance is both the cause and the result of our unique voting system. The Founding Fathers devised both our two-tiered legislature and the Electoral College fearing (pick one) “mob rule” or “genuine democracy.” The Electoral College prevents millions from having their voice heard in national elections. Three times, a presidential candidate has won 500,000 more votes than his opponent, only to lose the election. Senators from the 26 smallest states (representing 18% of the population) hold a majority in the Senate. Still, though most citizens are ignorant of these statistics, they are not stupid: majorities regularly favor dismantling the Electoral College.

But the system, designed to limit democratic participation, has succeeded. As fewer people believe that their votes matter, they lose interest in keeping track of events, and ignorance becomes reality. The contradiction becomes monumental when we periodically bond together to “bring democracy” elsewhere.

A vicious cycle develops: low turnout by the poor results in government that is far more conservative than the population; and politicians reaffirm their apathy by courting the middle class. Indeed, in countless subtle ways the process of voting in America is designed to restrict participation: voting on one work-day instead of weekends; massive voter suppression; computer fraud; and hostile right-wing operatives.

“Americanism” is a mix of contradictory images: competitive individualism balanced by paranoid conformism; an ideology of equality with a subtext of racial exclusion; and official church-state separation negated by the legislation of morality. These features come together in one truly exceptional symbol: the cult of the flag, which we literally worship. We have Flag Day, Flag etiquette and a unique national anthem dedicated to it that we sing, curiously, at sporting events. Twenty-seven states require school children to salute it daily.

But worship? Consider the Flag Code: “The flag represents a living country and is considered a living thing.” Indeed, religious minorities have refused to salute it specifically because they consider such action to be blasphemous. But dread of the Other and re-invigorated, manipulated support for the military creates religious fervor – and fearful politicians. All fifty state legislatures have urged Congress to pass a constitutional amendment to make defacing the flag a crime.

The myths of freedom and opportunity – two-thirds of us believe that success is within our control – meet the myth of the Puritan to form another exceptional characteristic. Since Puritans still perceive both morality and worldly success as evidence of their elect status, we are a nation in which the poor have no one to blame (and often to turn to) but themselves. By more than six to one, we believe that people who fail in life do so because of their own shortcomings, not because of social conditions.

We are exceptional among industrialized countries in failing to provide for pregnant and newly parenting workers; only two other countries do not mandate maternity leave. Reforms such as unemployment insurance came into effect in the U.S. thirty to fifty years after most European countries had introduced them. They remain highly popular there; but as low-income constituencies shrink, both Republicans and Democrats have felt free to erode them.

(Let me point out, by the way, that I compiled most of these statistics for my book prior to the economic meltdown of 2008 and long before the Depression of 2020.)

The results: Nearly four million children live with parents who had no jobs in the previous year. The U.S. is 22nd in child poverty, 24th in life expectancy, 24th in income inequality, 26th in infant mortality, 37th in overall health performance and 54th in fairness of health care. Even so, America’s health care system is the costliest in the world. We spend over $5,200 per person on health care, more than double what 29 other industrialized nations spent. This equals 15% of our GDP, compared to Britain’s 7.7%. We account for 50% of the world’s drug budget, and we were 28th in environmental performance, long before Trumpus (Trump = Us) trashed most of the nation’s regulatory agencies.

Americans naively consider themselves to be quite generous in helping poor nations. In fact, our Puritan judgment encompasses the whole world. We are 22nd in proportion of GDP devoted to foreign aid, and over half of it goes to client states in the Middle East. Indeed, nearly 80 % of USAID contracts and grants go directly to American companies. Nearly 70% of Europeans want their governments to give more aid to poor nations, while nearly half of Americans claim that rich nations are already giving too much.

By choice (the Puritan’s addiction of workaholism) or by necessity (the “McJobbing” of the economy), we work unceasingly. In 2003, Americans worked 200 to 350 hours – five to nine weeks – longer per year than Europeans. Indeed, this was four weeks longer than they themselves had in 1969. Vacations average two weeks; in Europe they average five to six weeks. We spend 40% less time with our children than we did in 1965. Europeans, who consistently choose more leisure over bigger paychecks, claim that they work to live, while Americans seem to live to work.

Even if we factor out economic issues, the Puritan residue remains. Just below the skin of consumer culture we judge ourselves by how hard we work, and we relax only when we have acquired the symbols of redemption. Even then, we keep working.

One reason we work so hard is to afford the national status symbol, the car. We own far more than other countries, both in total and per capita. The average household now has more cars than drivers. Consequently, America leads the world in greenhouse emissions, both absolutely – a quarter of the world’s total – and per capita. We spend ten hours per week driving. We park those cars next to houses that average more than twice the size of European homes.

But the shadow of radical individualism reveals itself in epidemics of loneliness and alienation. According to Jill Lepore, neuroscientists identify loneliness as “a state of hypervigilance” embedded in our nervous system, inherited from our prehistoric ancestors. In the past seventy years the percentage of American households consisting of only one person has risen from 9% to 25%. She concludes:

Living alone works best in nations with strong social supports. It works worst in places like the United States. It is best to have not only an Internet but a social safety net.

Loneliness makes us sick, and alienation – combined with unrealistic expectations of success –makes us exceptionally willing to shoot up a schoolyard or other public space.  For an excellent Depth Psychological perspective on the mass shootings of the past twenty years, read Glen Slater’s article A Mythology of Bullets.

For an excellent Depth Psychological perspective on the mass shootings of the past twenty years, read Glen Slater’s article A Mythology of Bullets.

Despite the talk show rhetoric, Americans have always been taxed at far lower rates than the rest of the developed world. Even before the Reagan years, taxes amounted to 31% of GDP, while most European countries were well over 40%. There are at least two primary results of these disparities. We provide far fewer social services, and economic inequality is far higher than in any other developed nation.

By 2000 one percent of us owned forty percent of the wealth. By 2020, the top one percent owned nearly as much as the entire middle class. We have entered a “new Gilded Age” of unregulated capitalism and conspicuous consumption, as I write in We Like to Watch: Being There With Trump. In the first three months of the Coronavirus pandemic, American billionaires saw their wealth increase by half a trillion dollars.

And that wealth is age-based. Excluding tiny enclaves like Switzerland, white American adults over age forty are the richest in the world. Even so, America has the highest rate of children living in families with incomes below poverty guidelines; this is the result of fewer public resources spent on children than in any industrialized nation.

Youths are by far our poorest age group. Mortality rates among children are also the highest, approaching Third World conditions. Yet even the wealth figures for the elderly reveal surprises. Most – some 35 million – are very well off. But twelve percent of them – again, the highest in the industrialized world – remain in poverty even after Social Security and Medicare.

With a shrinking economy, miniscule taxes on corporations, Puritan condemnation of poverty and the maintenance of empire, it is little wonder that so few resources remain for the poor. The U.S. spends more money on armaments than the rest of the world combined.

Even so, confidence in American institutions – government, religion and education – had been dropping every year since the early 1970’s – at least until 9/11/01. Here we return to mythic questions. A large and occasionally threatening population of Others is absolutely crucial to the perpetuation of the myth of American innocence. As long as the internal Black Other threatens to take one’s job (or one’s daughter), as long as one believes in the necessity of constantly striving in unsatisfying work to attain the symbols that serve as substitutes for a genuine erotic life, one will work unceasingly. In June of 2020, we can legitimately ask, Do Black Lives Really Matter?

Part Five

Christian nation mythologists pump themselves up with narratives of American exceptionalism and Christian domination. But sooner or later even their most devoted followers should begin to see that also depicting it as vulnerable to non-existent threats undermines the myth itself. – Sarah Posner

Nobody is more dangerous than he who imagines himself pure in heart; for his purity, by definition, is unassailable. – James Baldwin

Our compliant workforce is another aspect of American exceptionalism. Why, alone among developed nations, do we have no established political party that agitates for the rights of working and poor people?

https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/2e1ax_origami_entry_tea-party-movement.jpg?w=150 150w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/2e1ax_origami_entry_tea-party-movement.jpg?w=300 300w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/2e1ax_origami_entry_tea-party-movement.jpg?w=768 768w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/2e1ax_origami_entry_tea-party-movement.jpg?w=1024 1024w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/2e1ax_origami_entry_tea-party-movement.jpg 1100w" sizes="(max-width: 640px) 100vw, 640px" />

https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/2e1ax_origami_entry_tea-party-movement.jpg?w=150 150w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/2e1ax_origami_entry_tea-party-movement.jpg?w=300 300w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/2e1ax_origami_entry_tea-party-movement.jpg?w=768 768w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/2e1ax_origami_entry_tea-party-movement.jpg?w=1024 1024w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/2e1ax_origami_entry_tea-party-movement.jpg 1100w" sizes="(max-width: 640px) 100vw, 640px" />

Why have so many unionized, blue-collar, white men supported such obvious criminals, fakes and warmongers as Nixon, Reagan, both Bushes and Trumpus?

Over three centuries after Bacon’s Rebellion, when blacks and whites briefly united and nearly toppled the government of colonial Virginia, scholars still wonder – innocently – why a strong socialist movement never developed in America, as it did, at least for a while, almost everywhere else.

Karl Marx believed that every society would eventually evolve out of old-world hierarchy into capitalism, and inevitably capitalism would yield to socialism. The more advanced a nation becomes in capitalism, the closer it must be to embracing socialism. But socialists were baffled by how the United States defied this rule. No nation was more capitalist, yet no nation showed less interest in becoming socialist.

Werner Sombart focused on material abundance: socialism, he complained, had foundered in America “on the shoals of roast beef and apple pie.” Leon Samson saw that the real enemy of socialism was exceptionalism itself, because Americans give “a solemn assent to a handful of final notions—democracy, liberty, opportunity, to all of which the American adheres rationalistically much as a socialist adheres to his socialism.” In other words, radical individualism had become an ideology that overwhelmed our natural inclination to cooperate with each other.

Actually, Marx and Sombart were wrong, writes Allen Guelzo:

There had been an American socialism; they were reluctant to recognize it as such because it came not in the form of a workers’ rebellion against capital but in the emergence of a plantation oligarchy in the slaveholding South. This “feudal socialism,” based on race, called into question all the premises of American exceptionalism, starting with the Declaration of Independence. Nor were slavery’s apologists shy about linking this oligarchy to European socialism, since, as George Fitzhugh asserted in 1854, “Slavery produces association of labor, and is one of the ends all Communists and Socialists desire.”

The institution of slavery became the model for a broader economic / financial system in which corporate welfare, or “socialism for the wealthy” would exist only because of taxes on the middle class and massive budget deficits.

Academics, however, rarely consider the overwhelming presence of the Black Other, the elephant in the living room of their theories about exceptionalism. It is a simple fact that no other nation combined irresistible myths of opportunity with rigid legal systems deliberately intended to divide natural allies.

Whiteness implies both purity (which demands removal of impurities) and privilege. No matter how impoverished a white, male American feels, he hears hundreds of subtle messages every day of his life that invite him to separate himself from the impure.

Without racial privilege the concept of whiteness is meaningless. From the Civil War, when tens of thousands of dirt-poor whites died for a system that offered them nothing economically, to the Tea Partiers supporting politicians who blatantly promise to destroy their social benefits, white Americans have often had nothing to call their own except their relative position in the American caste hierarchy. We can only conclude that for them, and only in America, privilege trumps the potential of class unity.

Throughout both the developed world and their colonial outposts, the elite classes and their servants perceived left-wing organizing as rational, even logical antagonism to their rule, and they responded accordingly. Only Americans, however, saw communists as so polluting of our essential innocence, so un-American, so absolutely, irrevocably evil that they would create a Committee on Un-American Activities. has such fear, born in the Indian wars, the Salem Witch trials and the slave patrols, produced a surprisingly widespread consensus that any violations of human rights whatsoever are justified in suppressing the Other. Only in America have people proclaimed that they would rather be “better dead than red.”

Thirty years ago, the memory of our eighty-year crusade against Communism was fading quickly from memory – except among those who recognized its mythic and political benefits. But that residue of fear and hatred never disappeared, and – under a Democratic President – it soon reappeared as a series of narratives that blame every national problem on “the Russians.”

How ironic: nineteenth-century thinkers occasionally referred to American exceptionalism; but the first national leader to use it (in 1929) was Joseph Stalin, as a critique of American communists who argued that their political climate was unique, making it an “exception” to certain elements of Marxist theory.

The systematic manufacture of consent – based on terror of pollution by outsiders – is the ultimate meaning of American exceptionalism. The U.S. is unique among empires in convincing its own poor and working-class victims that they share in its bounty – and to pay for its expenses. “How skillful,” wrote Howard Zinn, “to tax the middle class to pay for the relief of the poor, building resentment on top of humiliation!” Noam Chomsky writes, “The empire is like every other part of social policy: it’s a way for the poor to pay off the rich in their own society.”

Chomsky adds, “… any state has a primary enemy: its own population.” But in the U.S., an efficient system of control, a “brainwashing under freedom,” has flourished like nowhere else. It combines free speech and press with patriotic indoctrination and marginalization of alternative voices, leaving the impression that society is really open. The system distributes just enough wealth and influence to limit dissent, while it isolates people from each other and turns them toward symbols that create loyalty. The real function of the media is “to keep people from understanding the world.”

By limiting debate to those who never challenge the assumptions of innocence and benevolence, it maintains the illusion that all share a common interest. When the boundaries of acceptable thought are clear, debate is not suppressed but permitted. But in this context, the loyal opposition legitimizes these unspoken limits by their very presence. The system exists precisely because of our traditional freedom of expression. Chomsky quotes a public relations manual from the 1920’s, (aptly titled Propaganda): “The conscious…manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is a central feature of a democratic system.”

We can criticize the national state from this anarchist perspective not necessarily out of a particular ideology – Caroline Casey suggests “believes nothing but entertain possibilities” – but because it is closest to a tribal perspective. Mass society as we know it is barely four centuries old. For most of human history we have lived in small communities in which individuals knew everyone else and experienced fulfilling relationships within a mythic and ritual framework. Human nature has never had time to adjust to the strife and alienation of modern and post-modern society. And it is precisely this disconnect that advertising and political propaganda take advantage of.

Compared to Americans, many Third World peasants are free in one respect: they have no myth of innocence. Their consent may be coerced, but the media cannot manufacture it for them. They, far more than our educated classes, can see. Where their history has not been completely destroyed, they can see that there has been essentially no difference in American foreign policy for over 150 years. It is perfectly obvious to them that the U.S. controls their resources and manipulates their markets, while protecting American companies from “market discipline.” They know more than we could ever know that talk of “free markets” is just talk.

They know that the only significant changes in First and Third World relationships have been in the resources themselves (first agricultural, then mineral, then human), and in the nature of the overseers (first European, then American, then local tyrants who serve the corporations.) To them, “globalization” is merely the latest top-down phrase that rationalizes such practices.

Ultimately, what makes us exceptional is this mix of overt propaganda, subtle repression of free thought and a deep strain of purposeful ignorance. We want to believe the story. Only in America has a historical collusion existed between national mythology and the facts of domination, between the greed of the elite and the naivety of the people, between fathers who kill their children instead of initiating them and youth who willingly give themselves up to the factories and the killing fields.

Our exceptionalism lies in the denial of our racist and imperial foundations and our continuing white privilege. Cornel West writes, “No other democratic nation revels so blatantly in such self-deceptive innocence, such self-paralyzing reluctance to confront the night-side of its own history.” And because our storytellers regularly remind us of how generous, idealistic, moral, divinely inspired and innocent of all sin we are, we can deny the realities of race, environment, empire – and death.

Part Six

America is not exceptional because it has long attempted to be a force for good in the world, it tries to be a force for good because it is exceptional. – Peggy Noonan

It is extremely dangerous to encourage people to see themselves as exceptional, whatever the motivation. – Vladimir Putin

…one of the reasons people cling to their hates so stubbornly is because they sense, once hate is gone, they will be forced to deal with pain. – James Baldwin

What are we to make of a creation in which the routine activity is for organisms to be tearing others apart…bones between molars, pushing the pulp greedily down the gullet with delight, incorporating its essence…and then excreting with foul stench and gasses the residue. Everyone reaching out to incorporate others who are edible to him.

The indigenous world imagined the Great Mother as both sustainer and destroyer. But modern people can only respond to Becker’s questions in dualistic terms. Either we feel the terror and are immobilized, or we construct myths of religion, romance and domination to transcend our fear of mortality. He argued that all human behavior is motivated by the unconscious need to deny this most fundamental anxiety.

Becker regretted that “we must shrink from being fully alive,” because seeing the world “as it really is, is devastating and terrifying,” and results in madness. Mystics, however, describe this insight as devastating to the individual ego, and a necessary, initiatory prelude to the unitive vision that transcends duality. Ancient devotees of Dionysus, as well as modern practitioners of Eastern and African-based religions, actually strive to attain this state. But for those who lack the containers of community and ritual, the unconscious fear of death is a primary motivator.

To the uninitiated modern person, the death of the ego and the death of the physical body are one and the same. And in America, the loss of identity (white, patriarchal, masculine, Christian, productive, growing, gainfully-employed, segregated into racially conformist neighborhoods, or simply privileged) seems to be equivalent to death of the ego. Yet the prospect of ecstatic escape from the confines of that ego continually beckons to us, and we respond in all manner of unconscious ways. Let’s try to understand yet another essential American myth, the denial of death.

Despite seeing great progress since the writings of Elizabeth Kubler-Ross and Jessica Mitford, American culture continues to deny and avoid the reality of death more than any other society. This is particularly curious, given our high degree of (perhaps superficial) religiosity. The myth of innocence represents the attitude of the adolescent who expects to live forever. It provides no space for acknowledging that death is a part of life, rather than its opposite. Some call death the most repressed theme of the twentieth century, comparable to the sex taboo of the 19th century. We still view it as morbid, and commonly exclude children from discussion of it. Many adults have never seen a corpse other than in the stage-managed context of the funeral parlor.

Kubler-Ross argued that since few really believe suffering will be rewarded in Heaven, “then suffering becomes purposeless in itself,” and doctors typically sedate the dying to lessen their pain. They are rushed to hospitals, frequently unconscious and against their will, and most die there or in nursing homes. Then the corpse disappears, not to be seen again until it has been “primped up to appear…asleep.” Euphemisms complete the ritual of denial. The “deceased” has “passed on” or “gone to his maker.” “How peaceful he looks.”

The purpose of the ritual is to repress the anxieties that arise when tending to a terminally ill patient. Relatives collude with medical personnel in an elaborate series of lies, maintaining the fiction of probable recovery until the dying person reaches the point of death. Typically, a doctor, rather than a minister, presides over the deathbed, keeping displays of emotion to a minimum. Adults deprive both children and the dying persons themselves of the opportunity to confront death.

Ironically, write Anthropologists Richard Huntington and Peter Metcalf, “In America, the archetypal land of enterprise, self-made men are reduced to puppets.” Then the body is embalmed, restored, dressed and transformed from a rotting cadaver into “a beautiful memory picture.” Neither law nor religion nor sanitation requires this process, and nowhere else but in North America is it widely done. In the last view the deceased seems asleep in a casket (often made of metal).

The ritual achieves two results. First, it insulates mourners from the process of decomposition, the finality of death and their own fears. Second, it minimizes cathartic expressions of grief. The funeral director, writes Mitford, “has put on a well-oiled performance in which the concept of death has played no part…” Wakes are generally pleasant social events, and mourners soon return to work. The mystery of death invites mourners to enter an initiatory space, but it closes too abruptly and too soon for any authentic transition or resolution. A veil that had been briefly lifted drops again.

We claim to believe that Christianity represents a victory over death, yet estrangement from nature is its central theme. Thus, to Americans, death must be either part of God’s plan or a punishment. Arnold Toynbee joked that death was “un-American,” an infringement on the right to the pursuit of happiness. By contrast, Native American tribal religions almost universally produced people unafraid of death, wrote Vine Deloria: “…the integrity of communal life did not create an artificial sense of personal identity that had to be protected and preserved at all costs.”

West African shaman Malidoma Some´ observes our characteristic refusal to give in to grief: “A non-Westerner arriving in this country for the first time is struck by how…(Americans) pride themselves for not showing how they feel about anything.” To him, we typically carry great loads of unexpressed grief. And this leads to a corresponding inability to experience joy: “People who do not know how to weep together are people who cannot laugh together.” This is a succinct, tribal definition of alienation – exile from the worlds of nature, community and spirit.

If we cannot grieve or tolerate the vision of the dark goddess and her bloody, dismembered son, then we cannot experience ecstasy either. We learn to tolerate pale substitutes: romance novels, horror movies (in which characters often refuse to die), the spectacles of popular music and sports, New Age spirituality, Sunday church and happy endings. We learn early to emphasize the light (including “lite”) to the eventual exclusion of the dark.

So our characteristic American expectation of positive emotions and emotional growth makes feelings of sadness and despair more pathological in this culture than elsewhere. Christina Kotchemidova writes, “Since ‘cheerfulness’ and ‘depression’ are bound by opposition, the more one is normalized, the more negative the other will appear.”

Ronald Laing argued that the modern family functions “… to repress Eros, to induce a false consciousness of security…to promote a respect for ‘respectability.’” To be respectable is to produce, and to look cheerful. American obsession with feeling good (“pursuing happiness”) is enshrined as a fundamental principle of the consumer society. As Kotchemidova explains,

Our personal feelings are constantly encouraged or discouraged by the culture of emotions we have internalized, and any significant deviance from the societal emotional norms is perceived as emotional disorder that necessitates treatment.

The average American feels real pressure to present him/herself as cheerful in order to get a job. Once he/she is employed, putting on a ready- made smile is simply not enough. “Corporations expect their staff to actually feel good about the work they do in order to appear convincing to clients.”

She argues that twentieth century America took on cheerfulness as an identifying characteristic. The new consumer economy of the 1920s called for cheerful salespeople and an American etiquette that obliged “niceness” and excluded strong emotionality. Among the dozens of self-help cheerfulness manuals, Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People (1936) sold more than fifteen million copies. In the 1950s, the media industry invented numerous ways, including the TV “laugh track,” to induce cheerfulness. In the 1980s, politicians discovered cheerfulness; all Presidents since Reagan smile in their official photos (none had done so before). The “smiley face” button sold over 50 million units at its peak in 1971 but remains one of our most recognizable icons.

It follows that depression has reached epidemic proportions in America – and that violence is so fundamental to our experience. Kubler-Ross wrote that our denial of death “has only increased our anxiety and contributed to our…aggressiveness – to kill in order to avoid the reality and facing of our own death.” Phillip Slater wrote of “our technologically strangled environment” in which impersonal forces impact us from remote, Apollonic distances and provoke us to “find a remote victim on which to wreck our vengeance.” This is one reason why Americans rarely protest the military’s mass killing of distant Third World people. Another reason, of course, is their ignorance of the news.

But America was characterized from the start by extreme violence. It was present in the “idea” of America – not the abstract ideals of the founding fathers, but the projection of darkness, instinct and lust onto the Other in the already demythologized world of the seventeenth century. By the Industrial Revolution of the 1840’s, Americans had been slaughtering Indians and enslaving Africans for over two centuries. Herman Melville took note of this and wrote that Indian hating had become a “metaphysic.” Technology certainly contributed to alienation, loneliness and the breakdown of extended families and father-son relationships. But as a seed of depression and long-distance violence, it fell on fertile soil that had been well prepared.

And history conspired. No one alive can recall the carnage of the Civil War; since then we have fought our wars across great oceanic expanses. With the ready availability of handguns, we slaughter each other in small-scale violence like no other people in history. Except for urban race riots, however, there had been no warfare on American territory for well over a century until the terrorist acts of 2001.

These factors all help to perpetuate the myths of innocence and exceptionalism. The final ingredient is the state of the media, in which news reporting, political spin and entertainment are now almost indistinguishable, when half of us get our news from social media or TV comedy “news” shows.

On the one hand, media colludes with our need to remain sheltered from the world and our impact upon it. “We are so desperate for this,” writes Michael Ventura, that we are willing to accept ignorance as a substitute for innocence.” On the other hand, even as violent programming perpetuates fear of crime and terrorism, television has desensitized three generations of Americans to the actual effects of violence.

We all know the statistics. We can theoretically take two populations of children and predict that, as young adults fifteen years later, those who watch more TV will be more violent than the group that watched less. Thus, there is a direct connection between the national denial of death in the abstract and America’s ferocious expression of literal violence. James Hillman concluded that death is “the ultimate repressed,” who returns “through the body’s shattered disarray,” an incursion “into awareness as ultimate truth.”

We innocently observe, we are shocked, and we quickly forget. In book talks I’ve often posed a trick question – When did you lose your innocence? – followed by another one – When did you lose it again? When an exceptional sense of personal and national innocence is so ingrained as ours is, every time it is punctured by circumstances it feels like the first time. In Chapter Eight of my book, I wrote of this experience after the attacks on the World Trade Towers:

The next day, a second wave of commentators offered more nuanced interpretations. Rabbi Marc Gelman, asked if America would be changed by this event, responded, “Yes, we have lost our innocence. We now know there is radical evil in the world.” It was out there, and Americans, mysteriously, had never heard about it. Psychologist Robert Butterworth’s son had asked him, “Daddy, why do they hate us so?” Staring mutely and miserably at the camera, he really didn’t know. His non-response assumed that viewers didn’t either. Such laments could have followed the Oklahoma City bombing, 1993’s WTC bombing, the TWA airliner bombing, the bombings of the destroyer Cole and Lebanon barracks, or any of the recent college or high school shootings. America, we were told, had lost her innocence.

From the perspective of outsiders, or of older cultures, or of the Other, losing our innocence is an absolutely necessary step for white Americans to step out of our adolescence and join the human community. But from within the myth of exceptionalism, losing our innocence is simply a temporary stage that precedes falling back asleep.

Never having confronted death directly, we must find a way to see it, by condoning violence or personally inflicting it upon others. Preferring vengeance to mourning, we are still the only nation to use atomic weapons. Americans invented napalm, cluster bombs and “anti-personnel” mines. We are stunningly unmoved by news of torture at Guantanamo, rape of prisoners in Iraq or police murders of unarmed African Americans, because innocence always trumps awareness. The nation that watches and exports thousands of hours of electronic mayhem and has more handguns than citizens is shocked – shocked! – every time a teenager massacres his schoolmates or a cop drives his car into a crowd of peaceful protestors.

Octavio Paz contrasted his own Mexican culture, which has an intimate relationship to the dark side of existence, with ours: “A culture that begins by denying death will end by denying life.” Such a nation desperately needs someone to save it – distract it – from the black hole of death, and to vanquish, rather than to accommodate those forces of darkness. Such a nation needs heroes. And it will get the heroes that it deserves. On the other hand, writes Caitlin Johnstone,

The principles of individual healing apply to collective healing as well. I have learned that an individual can experience a sudden, drastic shift in consciousness. I see no reason the collective can’t also. Of course humanity is capable of a transformative leap into health and maturity…The only people who doubt this are those who haven’t yet made such a leap in their own lives.