Part One

A dancer dies twice – once when they stop dancing, and this first death is the more painful. – Martha Graham

The 2010 film Black Swan is a deeply wise and convincing psychological account of the inner journey required of the ballerina protagonist in order to fully embody the dual female lead roles in a production of Swan Lake.

In Tchaikovsky’s original 1877 ballet, an evil sorcerer has condemned Princess Odette to live as a white swan during the day. Only at night, by the side of an enchanted lake created from her mother’s tears, can she return to human form. The spell can only be broken if one who has never loved before swears to love her forever, and Prince Siegfried does just that. But at a costume ball in which Siegfried must choose a wife, the sorcerer arrives with his daughter, Odile (the black swan), whom he has transformed to look like Odette, and Siegfried chooses her. Realizing his mistake, Siegfried hurries back to the lake and apologizes. She forgives him, but his betrayal cannot be undone. Rather than remain a swan forever, Odette chooses to leap into the lake and die, as does Siegfried. Ascending to Heaven, they remain united in love.

Since the original performance there have been dozens of productions, with all kinds of different conclusions, from tragic to happy. A lake created from her mother’s tears! Doesn’t that image speak to us all in this time of pandemic and environmental collapse? The binary opposition of Odette-Odile / black-white evokes the polarity of conscious-unconscious, or persona-shadow.  On the sociological level, it also evokes issues of race in America. (We find the dark or even projected other in many films. Gershon Reiter’s book The Shadow Self in Film addresses this theme. )

On the sociological level, it also evokes issues of race in America. (We find the dark or even projected other in many films. Gershon Reiter’s book The Shadow Self in Film addresses this theme. )

These opposites are in a dynamic tension in the form of extreme control of the body and its opposite, the need to abandon the ego and lose one’s self (mythologically, Apollo vs Dionysus, or perhaps Athena vs Aphrodite).

This is the psychic territory that Black Swan invites the viewer into. The plot revolves around a production of Swan Lake by a prestigious ballet company. It requires a ballerina to play the innocent and fragile White Swan, for which the emotionally cold Nina is a perfect fit, as well as the dark and sensual Black Swan, which are qualities better embodied by her earthy rival, Lily. While her delicate innocence and demeanor combined with technique and discipline are perfect for the White Swan, her challenge is to go beyond herself and undergo the metamorphosis into the Black Swan. She must be both/and rather than either/or.

Her quest is complicated by her relationship with her domineering mother, who long ago abandoned her own dreams of being a great ballerina, only to live her obsession through her daughter. Nina is 28 years old, the same age at which her mother had retired, but she lives emotionally as an innocent young girl, in a pink bedroom full of stuffed animals. “Nina” means “little girl” in Spanish. Her last name is Sayer (from which the story may well take us through “Say-er,” “Say her,” “Say her name,” and possibly all the way to “See-er” or “Seer.” We’ll see. Her mother seems to play the role of the sorcerer who keeps Nina trapped in the mother realm and unable to become whole.

Meanwhile, the name Lilly (rhyming with “Odile”) evokes the lily flower, which represents both chastity and the purity achieved through death. Dan Ross writes that Lilly

…is the familiar form of Lillith, the first woman who rejected Adam because she would not submit to a man. Lillith was considered evil because she was uninhibited and unrestrained, so she was banished (to shadow). This is a perfect description of Lilly who is all that Nina is not. It is not surprising that Nina fantasizes making love with Lilly.

The intense, competitive pressure and her obsessive perfectionism, combined with Nina’s desire to escape her mother’s spell causes her to lose her tenuous grip on reality and descend into hallucinations, suspicion, betrayal and apparent violence. Many reviewers focus on Black Swan’s depiction of madness. Yes, but to only perceive the film on this level is to miss its deeper significance for the viewer. Jadranka Skorin-Kapov writes,

…the film can be perceived as a poetic metaphor for the birth of an artist, that is, as a visual representation of Nina’s psychic odyssey toward achieving artistic perfection and of the price to be paid for it.

As progressives in 2020, nearly twenty years since the beginning of the “War on Terror”, when we are assaulted daily by the latest pronouncements of our pathologically narcissist leadership, we remember the words of Blaise Pascal: Men are so necessarily mad, that not to be mad would amount to another form of madness. As archetypal psychologists, we know that that society prefers to label anyone who questions our consensus reality as mad. And as mythologists, we remember that the original meaning of the word “competition” is petitioning the gods together. In a Jungian fantasy of individuation (or better, as James Hillman would have argued, Psyche and Eros), there is no binary opposition between Nina and Lilly. They are co-conspirators (“conspiracy” – to breathe together) in the opus, or great work, the soul work of the loss of innocence.

Nina is constantly looking into or reflected by mirrors in rehearsal spaces, dressing rooms, bathrooms and train windows.  Clearly, she is encountering shadow aspects of herself, especially when Lilly appears as friend, rival and lover.

Clearly, she is encountering shadow aspects of herself, especially when Lilly appears as friend, rival and lover.  This psychological challenge mirrors Tchaikovsky’s own enchanted lake, which was created from the tears of Odette’s mother. Ultimately, as part of this dance of self-knowing, the two begin to battle in a dressing room during a break in the performance. Nina throws Lilly into the mirror and breaks it before (in her hallucination) stabbing her.

This psychological challenge mirrors Tchaikovsky’s own enchanted lake, which was created from the tears of Odette’s mother. Ultimately, as part of this dance of self-knowing, the two begin to battle in a dressing room during a break in the performance. Nina throws Lilly into the mirror and breaks it before (in her hallucination) stabbing her.

From a psychiatric point of view, Nina is “cracking up.”  But traditional wisdom would see this as an essential, if dangerous step in the breakdown of an ego, a constricted sense of identity, a fall out of the familiar into the liminal. Only then, as if she has incorporated Lilly’s essence, as if this scene was a metaphorical Eucharist, can she embody the black swan, which she does fully in the following act. Hillman places the movement toward black in an alchemical context:

But traditional wisdom would see this as an essential, if dangerous step in the breakdown of an ego, a constricted sense of identity, a fall out of the familiar into the liminal. Only then, as if she has incorporated Lilly’s essence, as if this scene was a metaphorical Eucharist, can she embody the black swan, which she does fully in the following act. Hillman places the movement toward black in an alchemical context:

Therefore, each moment of blackening is a harbinger of alteration, of invisible discovery, and of dissolution and of attachments to whatever has been taken as dogmatic truth and reality, solid fact, or dogmatic virtue. It darkens and sophisticates the eye so it can see through.

Nina’s soul opus moves in two seemingly opposite directions: towards incorporating her dark twin, and away from the suffocating grasp of her mother. But neither movement can happen without the simultaneous work of the other. Nina fully inhabits or embodies the Black Swan in performance, thus achieving her goal of perfection, only after she has broken from her mother, broken her dressing room mirror and broken Lilly’s (or perhaps her own) body.

Part Two

A man needs a little madness, or else he never dares cut the rope and be free! – Nikos Kazantzakis

What is madness but nobility of soul at odds with circumstance? – Theodore Roethke

The quest to be perfect may well represent the quest to be whole, even if wholeness includes imperfection. See Marion Woodman’s book Addiction to Perfection. Beyond that, I can’t speculate on the feminine mysteries of escaping the grasp of the mother, partially because, traditionally, most women have had to wrestle with the reality of ultimately becoming mothers themselves. And, since the Greek myths were written down within a deeply patriarchal culture, the great majority of them describe the quests of the masculine, solar, heroic nature. Jungians have tended to resolve this tricky issue by arguing that these are stories of the individuation of the masculine principle within all people, regardless of gender. I don’t know if all women would agree.

We can interpret some of them as initiation stories that involve breaking out of the localized realm of the mother so as to emerge and return, acknowledged as adult men by the broader realm of the community. My essay “Initiation and the Mother” describes several distinct strategies described in myth. Some of these routes to the father are more successful than others, but it’s worth noting that the name of the hero Heracles means “the glory of Hera.” In another essay I consider “The Spell of the Mother.”

Does Nina kill her dark twin or completely accept her in order to fully embody the dual roles of white and black swans?Does she go mad? Must she descend into madness in order to achieve the perfection of her art? Does she heal from the madness? What, after all, is madness? From the soul’s perspective, can madness have a

purpose? In an earlier essay I address madness in America: Why are Americans so Freaking Crazy?

Let’s not forget that Black Swan, like any great work of art, is not only about the personal or internal; it’s also about society and the external.

Misogynists and imperialists though they were, scientists that they would eventually become, the Greek mythmakers understood very well that this world contains a basic element beyond rationality. Their holy pantheon included a place for Dionysus, the god of madness. The classicist Walter Otto wrote, “A mad god exists only if there is a mad world which reveals itself through him.” And the Greeks also understood that madness could very well be a necessary stage in knowing oneself, as I write here and here.

Does Nina literally stab (and perhaps) kill herself, or is film action symbolic? What really matters, as in all listening to stories throughout time, is what is evoked in us. “Reality” – for both her and us – shifts regularly as she alternately conflicts with, makes love with and then kills her shadow double. Is it herself she kills, that she makes love with? In the end, does she die physically, or is this a symbol of initiation? As her life slips away from the fatal wound, Nina mutters, “I felt it. Perfect. I was perfect.” The final shot, rather than the traditional fade-to-black, is a fade-to-white, as if the white swan / childish / innocent / uninitiated “niña” has died, to be replaced by the black swan of experience.

Dan Ross concludes that

…her death is the price we pay when we give ourselves over to the archetypal completely without maintaining hold on the totality of our personality and its roots in the outer world…The risk in integration of the shadow is one can be consumed by it and overidentify with it and become psychotic. So Nina goes from one Swan to another but remains a swan, inflated, disconnected from the outer world, relationships, and in the end dies…She was unable to keep the two realms in tension, the swan realm and the human realm.

I disagree (although his assessment may well be more relevant in my discussion of a second film, in Part Six of this essay). In tragic drama, as in any dream, death is symbolic of what needs to die so that something greater, or deeper, may be born. Readers of my book Madness at the Gates of the City: The Myth of American Innocence may recall that there has been an ongoing academic dispute over the ending of Euripides’ play The Bacchae and its meaning. Do Cadmus and Agape make Pentheus whole again by reconstituting his dismembered body? Is that play about a successful initiation or a failed initiation? The rational mind may struggle with such questions, but the soul lives them, and does not require the easy escape of answers. As the director character in Black Swan says, Swan Lake’s Odette “…in death finds freedom.”

Part Three

Whoever isn’t busy being born is busy dying. – Bob Dylan

In mythology, swans (which we naturally assume to be white) are linked to Aphrodite, Artemis, Apollo, Brigid and the Virgin Mary. Solar gods such as Zeus and Brahma, White Buffalo Calf woman and the Celtic deities Belanus and Lugh descend from Heaven disguised as swans. Saraswati rides a swan. Various sources claim that swans symbolize purity, grace, beauty, loyalty (they mate for life), unity, love, hope and transformation (they migrate, and the Ugly Duckling transforms into one). As such, they are popular images on jewelry, T-shirts, tattoos, coffee mugs and every kind of souvenir. Above all, the white swan embodies the attributes of spirit.

In Chapter Two of my book I discuss the differences between spirit and soul:

Concepts, like Apollo, are detached; they neutralize our direct participation in the world, distancing us by relying on the eye’s passivity, assessing from safe distances. Percepts are involved, relying on the “secondary” senses (olfactory, tactile, acoustic.) We are “perceptive” when we penetrate to the core. However, each requires the other – what we might also call soul and spirit – for completion, since life will not be confined to a single mode of knowing. Spirit is transcendent and soul is immanent. Zen teacher John Tarrant writes:

“…where spirit is too dominant, we are greedy for pure things: clarity, certainty, and serenity… (but) soul in itself does not have enough of a center…If soul gives taste, touch, and habitation to the spirit, spirit’s contribution is to make soul lighter, able to escape its swampy authenticity, to enjoy the world without being gravely wounded by it.”

Historians portray Greek civilization as extremely rational. But the Greeks themselves imagined a balance between the brothers, which they enshrined at Delphi, their religious center. Apollo relinquished it to Dionysus for three months each year.

The history of religion is an unstable relationship between these opposites, with rebellious impulses periodically threatening patriarchal control. Perhaps all history oscillates between Apollonian order and Dionysian energy. Cultural stability, however, requires a dynamic, ever-shifting balance. Too much sunshine dries us up, while excess moisture rots us and drives us crazy. Extreme order leads to stagnation, dogma and authoritarianism; too much reliance on the intuitive soul brings chaos, anarchy and collapse. Emphasizing one extreme, we eventually endure the other as a correction. When society literalizes Apollo’s spiritual beauty into formal religion, correct behavior and rational science, then literalized – and potentially violent – Dionysian subcultures arise.

The black swan is a highly evocative image in its own right and often seems to invite the internal movement into the dark spaces of soul.

Well before this film appeared in 2010, we find many references in popular culture. The Black Swan was a 1942 Tyrone Power swashbuckler pirate film based on a 1932 novel of the same name by Rafael Sabatini. At least eleven other writers (including Thomas Mann) have published short stories or novels with Black Swan as title. There are at least three independent Black Swan bookstores, in California, Kentucky and Virginia. There’s a Black Swan brand of barbeque sauce, and a Black Swan home décor store in Connecticut. Black Swan Green is the name of an English village in the novel of the same name by David Mitchell. Singers and rock bands have recorded at least twelve separate songs, albums – and an opera – with Black Swan in the titles.

Black Swan Theory is a metaphor used by economists and financiers. Black swan events are characterized by their extreme rarity, their severe impact, and the widespread insistence they were obvious in hindsight. The term is based on an ancient assumption that actual black swans did not exist – until they were discovered in the wild.

The phrase “black swan” itself derives from the 2nd-century Roman poet Juvenal‘s characterization of something being “rara avis in terris nigroque simillima cygno” (“a rare bird in the lands and very much like a black swan”). Philosophers such as John Stuart Mill, Bertrand Russell and Karl Popper have used the metaphor to describe the fragility of any system of thought. A set of conclusions is potentially undone once any of its fundamental postulates is disproved.

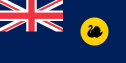

But by far the most common use of the term is in Australia, where “swan” almost always implies black swan. It is Australia’s  only native swan and is an official symbol for the state of Western Australia, as depicted on its flag and coat-of-arms. The symbol appears on Australian coins, postage stamps,

only native swan and is an official symbol for the state of Western Australia, as depicted on its flag and coat-of-arms. The symbol appears on Australian coins, postage stamps,  logos, mascots, sports teams, businesses, corporations, railways, universities, hospitals, mines, religious heraldic emblems, a literary magazine and several dozen place names including streets, towns, districts, rivers and islands.

logos, mascots, sports teams, businesses, corporations, railways, universities, hospitals, mines, religious heraldic emblems, a literary magazine and several dozen place names including streets, towns, districts, rivers and islands.

So much for the swan as symbol of national pride, or as gang color, if you prefer. But more to our purposes, it seems that “black swan” may also indicate a grudging acceptance of the nation’s own dark side, its indigenous, Aboriginal people who long before had named most of those places with terms that translate as black swan. Indeed, in the 1920s anthropologists recorded a man known as the “last of the black swan group” of the Nyungar people, who claimed that their ancestors were once black swans who became men.

Part Four

Every act of creation is first an act of destruction. – Pablo Picasso

Whatever white people do not know about Negroes reveals precisely and inexorably what they do not know about themselves. – James Baldwin

As long as we are at home in the body, we are absent from the Lord. – Increase Mather

Cut loose from the earth’s soul, they insisted on purchase of its soil, and like all orphans they were insatiable. It was their destiny to chew up the world and spit out a horribleness that would destroy all primary peoples. – Toni Morrison, A Mercy

I’d like to imagine that the Australian stories of black swans who became men refer to times (as in Greek myth) when gods and mortals walked the Earth together in harmony, when soul and spirit, body and mind, male and female or nature and culture were not so terribly divided as they are in our post-modern language, religion, environment and politics.

For hundreds of years, these polarities have been most concretely symbolized by black and white, leading to definitions of “black” that include:

– Causing or marked by an atmosphere lacking in cheer

– Not conforming to a high moral standard;

– Being without light

– Unclean

Black: the Black Death, black shirts, black cats, black crows, Black Panthers, black leather, black holes, black magic, the black knight, the black inquisitor, the black-clothed Puritan, the chimney sweep, the witch, the magician, the Grim Reaper, the Heart of Darkness, and of course, Black people. Our mythologies and theologies create values that praise a “white” world. Hillman writes:

…the negative and privative definition of black promotes the moralization of the black-white pair. Black then is defined as non-white, and is deprived of all the virtues attributed to white. The contrast becomes opposition, even contradiction…(and) gives rise to our current Western mind-set, beginning in the 16th and 17th centuries, the Age of Light, where God is identified with whiteness and purity, and black…becoming ever more strongly the color of evil.

Indeed, well before the age of colonialism, it was obvious to Europeans that blackness lacked the virtues associated with whiteness. In 1488 it was nothing unusual for Pope Innocent (!) VIII to give African slaves as presents to his cardinals.

But depth psychology – and Black Swan – insist that the more we identify with white, the more seductive black becomes. Above all, however, black is terrifying because it threatens (or invites) the collapse of the whole house of cards. I quoted Hillman above:

Therefore, each moment of blackening is a harbinger of alteration, of invisible discovery, and of dissolution and of attachments to whatever has been taken as dogmatic truth and reality, solid fact, or dogmatic virtue. It darkens and sophisticates the eye so it can see through.

We are all well aware in our bones, in our indigenous roots, that the white imagination, white thinking and even white privilege are profoundly unsatisfying. At that level we all know that our fear and hatred of both the internal, Black Other and the external, Red Other (originally the Red Indian, and for most of the 20th century, the Red Communist) merely cover over our envy and our desire to make peace with them and ourselves. However, we are also well aware that our demythologized world no longer provides secure ritual containers for the painful work of remembering who we really are. D. H. Lawrence knew this a hundred years ago:

I am not a mechanism, an assembly of various sections.

and it is not because the mechanism is working wrongly, that I am ill.

I am ill because of wounds to the soul, to the deep emotional self,

and the wounds to the soul take a long, long time, only time can help

and patience, and a certain difficult repentance

long difficult repentance, realization of life’s mistake, and the freeing oneself

from the endless repetition of the mistake

which mankind at large has chosen to sanctify.

So, while black (as descent into darkness and as African-American culture) invites America to heal the world and heal itself, most of us still take the easier way out, into hatred and scapegoating.

Black Swan, for all its references to a classical art form, is an American film. It takes place entirely in America’s cultural center. We view it, regardless of our superficial idealisms and ideologies, as Americans. And not just as Americans, but as Christians. Hillman writes:

You may be Jew or Muslim, pay tribute to your god in Santeria fashion, join with other Wiccas, but wherever you are in the Western world you are psychologically Christian, indelibly marked with the sign of the cross in your mind and in the corpuscles of your habits. Christianism is all about us, in the words we speak, the curses we utter, the repressions we fortify, the numbing we seek, and the residues of religious murders in our history…Once you feel your own personal soul to be distinct from the world out there, and that consciousness and conscience are lodged in that soul (and not in the world out there) and that even the impersonal selfish gene is individualized in your person, you are, psychologically, Christian.

Elsewhere, he places mental illness within this context:

As long as we are caught in cycles of hoping against despair, each productive of the other, as long as our actions in regard to depression are resurrective, implying that being down and staying down is sin, we remain Christian in psychology…Yet through depression we enter depths and in depths find soul. Depression is essential to the tragic sense of life…It reminds of death. The true revolution begins in the individual who can be true to his or her depression.

So we speak of Black Swan in American language, where the fundamental symbolism of white and black has never relaxed its hold on our imaginations. Also a hundred years ago, Carl Jung wrote,

When the American opens a…door in his psychology, there is a dangerous open gap, dropping hundreds of feet…he will then be faced with an Indian or Negro shadow.

Linguistic research indicates that some languages have only one color distinction: black and white. In languages with a third color term, that term is invariably red. How ironic that over time, in a curious blend of history and archetype, the American soul projected itself in red, white and black images, as I describe in Chapter Seven of my book. White, of course, speaks to us of our national sense of innocence, while in our language and mythology, black and red came to represent the “Others” who threaten us from within and from without.

As early as the late seventeenth century, America’s primary model for class distinction (and class conflict) had become relations between white planters and black slaves, rather than between rich and poor. The new system, writes Theodore Allen (author of The Invention of the White Race), insisted on “the social distinction between the poorest member of the oppressor group and any member, however propertied, of the oppressed group.”

Consider that statement again. This our American heritage. In most parts of the country, for most of American history, despite the ideology of freedom and equality, absolutely everyone understood that white skin color conveyed infinite privileges over anyone with black skin, regardless of one’s economic status. And the brutal polarity of identity received religious confirmation. Since poverty equaled sinfulness (to the northern Puritan) and black equaled poor (to the southern Opportunist), then it became obvious that blackness equaled sin.

The process of exclusion and subordination required a massive lie about black inferiority that has been enshrined in our national narrative. “After all,” writes activist Tim Wise, “to accept that all men and women were truly equal, while still mightily oppressing large segments of that same national population on the basis of skin color, would be to lay bare the falsity of the American creed.” Similarly, the French philosopher Montesquieu wrote, “It is impossible for us to suppose these creatures to be men, because, allowing them to be men, a suspicion would follow that we ourselves are not Christian.”

The myth of the Old South, writes Orlando Patterson, stated that the presence of the Other, not a slavery-based economy, had caused its shameful defeat in the Civil War (or, the “War of Northern Aggression”). The ex-slave symbolized both violence and sin to an obsessed society. He was “obviously” enslaved to the flesh, and his skin invited a fusion of racial and religious symbolism. His “black” malignancy was to the body politic what Satan was to the soul. “The central ritual of this version of the Southern civil religion…was the human sacrifice of the lynch mob.

In 1899, before torturing him, ten thousand Texans paraded their black victim on a carnival float, like the King of Fools, like Dionysus in the Anthesteria, or like Christ at Calvary. Patterson writes, “…the burning cross distilled it all: sacrificed Negro joined by the torch with sacrificed Christ, burnt together and discarded…”

like the King of Fools, like Dionysus in the Anthesteria, or like Christ at Calvary. Patterson writes, “…the burning cross distilled it all: sacrificed Negro joined by the torch with sacrificed Christ, burnt together and discarded…”

But in 2020 we continue to make a terrible mistake when we locate racism exclusively in the South, or exclusively among reactionaries, blatant racists or the uneducated. Prior to the Civil War, Northern mobs attacked abolitionists on over two hundred occasions.

Joel Kovel asserts that there are two kinds of racism. One is the obvious dominative racism that developed in close contact (including the privilege of rape) between master and slave. The second – aversive racism – arose from Puritan associations of blackness with filth. De Tocquevile wrote in Democracy in America that prejudice “appears to be stronger in the states that have abolished slavery than in those where it still exists; and nowhere is it so intolerant as in those states where servitude has never been known.”

Indeed, New England had about 13,000 slaves in 1750. In 1720, New York City’s population of seven thousand included 1,600 blacks, most of them slaves. And the two colonies with the strongest religious foundations – Massachusetts and Pennsylvania – were the ones that first outlawed “miscegenation.”

The terrible logic of “othering” – its logical conclusion – takes hatred beyond the requirements of capitalism, beyond the entertainment uses of race, all the way to genocide. Again, as recently as hundred years ago, twenty-seven states passed eugenics laws to sterilize “undesirables.” A 1911 Carnegie Foundation “Report on the Best Practical Means for Cutting Off the Defective Germ-Plasm in the Human Population” recommended euthanasia of the mentally retarded through the use of gas chambers.

Gas chambers.

The solution was too controversial, but in 1927 the Supreme Court, in a ruling written by Oliver Wendell Holmes, allowed coercive sterilization, ultimately of 60,000 Americans.

The last of these laws were not struck down until the 1970s. But now, with the coronavirus pandemic throwing millions out of work and onto the streets, the most extreme forms of gratuitous cruelty are re-emerging, with several prominent Republicans hinting that it would be better to let thousands of elderly – and Black and Brown – people die rather than keep the economy (and Trumpus’ re-election chances) in prolonged jeopardy. I’ll speak more about euthanasia below.

For some three hundred years, the distinction between black and white, with all of its moral implications, has remained absolutely central to white, Christian identity. And especially in times of economic uncertainty, any factual or emotional arguments to the contrary – or gestures of black equality – continue to provoke immense anxiety in the white mind and justify the most reactionary politics. In 2020, ten years after Black Swan was released, whites in Georgia lynched a black man for the crime of jogging through their neighborhood.

Part Five

To become an American is essentially to divest oneself of a past identity, to make a radical break with the past. – Herman Melville

…the world’s fairest hope linked with man’s foulest crime. – Herman Melville

What is this standard of “whiteness” by which Europeans and Americans have defined themselves for so long? My book argues that American whiteness is actually a perceived “not-redness” and “not-blackness.” In other words, countless White people believe that they know who they are because they lack the characteristics of the Other: primitive, lazy, irrational, impulsive, violent, untrustworthy or promiscuous.

And let’s be crystal clear about this. These are all psychological projections through which White Europeans have perceived people of color throughout the Third World in order to justify the terrible crimes of colonialism and convince themselves of their own innocence. And for a thousand years they have sent their young men to rape, slaughter and die for God’s will to triumph, often perpetrating the most hideous atrocities upon the truly innocent “for their own good.”

Taking this moral disorder to its pathological extreme, Captain Ahab believes that the white whale that men call Moby Dick is the embodiment of pure evil. And let’s be clear about this as well: why does Ahab hate the whale with such malicious intensity? Because on a previous voyage, the whale had taken his leg in self-defense while Ahab was hunting him. In his personal (and national) madness, Ahab, lifelong butcher of whales, has convinced himself that Moby Dick had victimized him, and has taken on the role of the Old Testament god of vengeance.

But why a white whale?

Chapter 42 (The Whiteness of The Whale) has been described as “…the heart of the entire work.” Melville begins it with the common ideas of whiteness symbolizing beauty, innocence and goodness. But then he addresses the mystery of identity that propels our hateful obsessions about the Other:

…there yet lurks an elusive something in the innermost idea of this hue, which strikes more of panic to the soul than that redness which affrights in blood…which causes the thought of whiteness, when divorced from more kindly associations, and coupled with any object terrible in itself, to heighten that terror to the furthest bounds. Witness the white bear of the poles …that the irresponsible ferociousness of the creature stands invested in the fleece of celestial innocence and love; and hence, by bringing together two such opposite emotions in our minds, the Polar bear frightens us with so unnatural a contrast.

…even the king of terrors, when personified by the evangelist, rides on his pallid horse…it is at once the most meaning symbol of spiritual things, nay, the very veil of the Christian’s Deity; and yet…the intensifying agent in things the most appalling to mankind…Is it that by its indefiniteness it shadows forth the heartless voids and immensities of the universe, and thus stabs us from behind with the thought of annihilation?…is it for these reasons that there is such a dumb blankness, full of meaning, in a wide landscape of snows – colorless, all-color of atheism from which we shrink?…pondering all this, the palsied universe lies before us a leper…And of all these things the Albino whale was the symbol. Wonder ye then at the fiery hunt?

Perhaps Melville was also acknowledging the chasm of meaningless that lies just below the surface of American identity and its assumptions about race and innocence. Interested readers should read Richard Slotkin’s great Regeneration Through Violence trilogy.

Gabrielle Bellot writes that just below the narrative of Moby Dick is the theme of race:

…it is a template for Melville’s, and our, America: a world populated as much with gestures towards racial equality as with casual racist assumptions…chasing Moby Dick, that avatar of whiteness, means fighting against the meaninglessness of the world, hoping that, through some bloody violence, life-purpose will bloom into existence. Ahab pursues the whale out of a manufactured anger, in a quest to give his life some vague value…

Six years after the publication of Moby Dick and three years before the Civil War, Melville completed his thinking about the white / red / black triad of American innocence, writing (in The Confidence-Man) of “Indian hating.” It was a unique dimension in which religious zeal, barbaric cruelty, capitalist land-grabbing and sacrificial ritual merged to create genocide. What Ahab had attempted to do to the white whale, his nation had been doing to its original inhabitants for 250 years. It was so ingrained in the national character that by Melville’s time, hatred of Indians had become a “metaphysic.”

Nearly a hundred and seventy years after Moby Dick, millions – perhaps tens of millions – of Americans continue to wrestle, knowingly or not, with the question of identity. Who the Hell are we? Are we nothing more than “not the Other”? Does our “manufactured anger” – or more accurately, displaced anger – give our lives “some vague value”? Is there still a positive definition of “American” that we can speak out loud without laughing or weeping? The good news is that countless good-hearted liberals have been offered the opportunity to awaken from their life-long trance of innocence and privilege. The bad news…well, you know the bad news. For more on the issue of white privilege, see my essays “Privilege” and “Affirmative Action For Whites.”

…this is the crime of which I accuse my country and my countrymen and for which neither I nor time nor history will ever forgive them, that they have destroyed and are destroying hundreds of thousands of lives and do not know it and do not want to know it…but it is not permissible that the authors of devastation should also be innocent. It is the innocence which constitutes the crime. – James Baldwin

Part Six

Truth and reality in art do not arise until you no longer understand what you are doing and are capable of but nevertheless sense a power that grows in proportion to your resistance. – Henri Matisse

Why is art so expensive? Otherwise, no one would buy it. – “Max”

From a very famous, Oscar-winning (Best Picture and Best Actress) film to a film almost no one saw:

Quite by chance (?), the same week in 2010 that I first saw Black Swan in a theater, I also found the 2002 film Max on Netflix. It’s a speculative account of Adolf Hitler’s life during the fall and winter of 1918. This was just at the end of World War I, when Germany was destitute, and the impoverished veteran was wavering between his ambition to be a successful artist and the temptation of extremist politics. Indeed, Russia had recently had a revolution and all of Germany was vacillating between the far left and the far right.

Americans have only been able to imagine Germany’s condition at that time by seeing 1972’s Cabaret, the best-known film about Weimar Germany, which is set much later, in 1931, when the Nazis where on the verge of taking power. For a darker and probably more accurate presentation, see the recent German TV series Babylon Berlin, which takes place in 1929 (also on Netflix).

We think we’re familiar with the all-powerful Fuhrer, and for 75 years, from both right and left, we have universally cited his image as the embodiment of pure evil. However, that is an archetypal image, a projection from the collective unconscious, from us. As an archetype, it is a potential characteristic we all carry.

This energy was embodied most famously by one person, roughly from 1920 to 1945. Max is the only film that I’m aware of that has wondered how that archetype chose that particular man; it’s the only film that has attempted to depict his precarious psychological state before he became a public figure.

What was that state? Liminality – the condition of “betwixt-and-between”, when one has been torn loose from everything one once knew to be true, when one’s fate hangs in the balance. It’s the condition that traditional societies once recognized. Such societies provided the elders and bounded ritual conditions to guide their initiates through the terrible passage to adulthood. In the extreme, such a passage went through the territory of re-living old trauma.

Black Swan and Max deal with the same theme: the absolutely essential encounter with one’s early psychological wounds – what we have repressed and condemned to the “dark side” of consciousness – in order to access and offer our gifts to the world. This is a common, even clichéd theme these days, but both films had me asking myself, “What are we willing to pay attention to? Just how much of our personal and collective darkness are we willing to know, to welcome, to love? What are we willing to sacrifice? How much are we willing to pay in order to manifest a truly creative life?” As viewers know, the ballerina does enter the heart of darkness and does give the performance of a lifetime, but she pays a severe price.

Similarly, in this film, the fictional Jewish Munich art-dealer Max Rothman becomes a reluctant mentor to the 29-year old Adolf Hitler, despite the younger man’s anti-Semitism. He sees that, below the anger, Hitler has an “authentic voice” and encourages him to “go as deep as you possibly can” in order to create something truly valuable. They argue about the purpose of art. Rothman, contrasting the hesitant and insecure Hitler with the impassioned, left-wing artists Georg Grosz and Max Ernst (both historical figures), argues, “It doesn’t have to be good. It doesn’t have to be beautiful. It just has to be true.”

But there is a second mentor. The right-wing army captain Karl Mayr (also an actual historical figure), senses Adolf’s intellectual and oratorical potential, his untapped charisma, and an uninitiated, pathological self-hatred that can be very useful to the anti-democratic cause. He arranges for the army to pay Hitler’s living expenses while he masters the arts of propaganda and instigation of mob violence. Hitler goes on to begin his speaking career by invoking German innocence: Germany had been defeated because the good, pure, brave Germans had been “stabbed in the back” by Communists and the traditional Others, the Jews.

Adolf can go either way; he can still possibly inhabit his better self and reject his darker potential. But Max Rothman can only offer the enticements and mild satisfactions of the same kind of secular liberalism that so many of us would reject two generations later. Mayr offers him ritual. It may be ritual that has been twisted and deformed, but it is still ritual, something that our indigenous souls recognize inherently.

And he offers Adolf a place within a community (twisted as it is) of hate and scapegoating, something that the Teutonic mind has been familiar with for a thousand years. Hitler is on his way to becoming the latest in a long line of charismatic German personalities who have manipulated mass resentment of the rich and turned it against the weak. For more on this theme, read The Pursuit of the Millennium by Norman Cohn.

The traumas of poverty and racism have condemned millions to lives that Thomas Hobbes described as “nasty, brutish and short.” Predictably, many men have arisen from these conditions to manifest their worst potentials, to go for power instead of love, to join their oppressors and participate in the perpetuation of these conditions, as so many police are doing right now all across the country.

But after thirty years in the Men’s Movement, I’ve been fortunate to have met many men (such as Louis Rodriguez) who survived the worst excesses of urban street life to become poets, teachers, musicians and activists. I recall reading the autobiographies of Malcom X and Claude Brown. Although far more have not succeeded, these lives offer us models of how things could be, given the presence of authentic mentors at the right time. For so many others, we wonder, “What if?”

https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/2003_max_007-1.jpg?w=150&h=102 150w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/2003_max_007-1.jpg?w=300&h=203 300w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/2003_max_007-1.jpg?w=768&h=521 768w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/2003_max_007-1.jpg 900w" sizes="(max-width: 475px) 100vw, 475px" />

https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/2003_max_007-1.jpg?w=150&h=102 150w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/2003_max_007-1.jpg?w=300&h=203 300w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/2003_max_007-1.jpg?w=768&h=521 768w, https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/2003_max_007-1.jpg 900w" sizes="(max-width: 475px) 100vw, 475px" />Noah Taylor as young Hitler

Max is a “What if?” story. Though they never meet, the two angels of Hitler’s nature compete for his soul, and as no viewer of the film can miss, for the soul of the entire world. Rothman, a champion of the new Expressionism, tells him, “You’ve got to take all this pent-up stuff that you’re quivering with and hurl it onto the canvas…Get out of politics…If you put the same amount of energy into your art as you do into your speeches, you might have something going.” But Hitler’s attempt to tap into his pain and rage goes nowhere artistically. Are his wounds too strong, his discipline too weak, or his talent simply absent? Perhaps all three.

But there is an easier way out (one that Black Swan’s Nina does not take) – the lure of scapegoating others as a way to deny his pain. Mayr’s advice is superficially similar but more convincing: “You’ve got your own talent.” – which clearly has nothing to do with painting – “Just let it out!”

The difference between this fictional Hitler and fictional Nina is critical and instructive. Because she is both deeply talented and highly disciplined, she is able (at least for a while) to hold the almost unbearable tension between her angel and her demon. Some might say that because she symbolically kills the demon, she can’t hold that tension for long. But she does make great art – if only for a moment – and contributes a lasting gift to the dance world. Adolf, on the other hand, is at best a second-rate artist, and he simply cannot improve his technique or – more importantly – work the terrible nature of his soul.

But he does “go deeper,” and he begins to muster a particular discipline that will focus on the development of a charismatic personality (from persona, mask). Apparently having made his choice between art as art and art as propaganda, he tells Max,

Go deeper, you said. I went deep. Deeper than any artist has gone before! This is the new art! Politics is the new art!…Art and politics equals power!

Late in the film, Max realizes that Hitler’s art is “futuristic kitsch.” Nevertheless, he attempts to channel that ferocity into the art world, where it might be less harmful to society: “You finally found your voice – the future as a return to the past.” But Hitler, as we know, will succumb to the lure of that mythical past and potentially future greatness. The film ends on Christmas eve, 1918, as Max is murdered by thugs whom Hitler had provoked.

Though not portrayed in Max, less than two weeks later, leftists would go on general strike in the violent Spartacist uprising. Hitler’s fascist allies will prevail, and Germany will begin its spin into that future.

Here is both the contrast with the ballerina and the frightening commentary on our current culture and politics. Nina will crack the masks of Black and White in dramatic expression, while Hitler will retreat behind a different mask and inhabit it for an entire nation. With neither her talent, nor her commitment, nor an artistic community like hers – an authentic ritual container – he falls victim to his own darkness and the peculiar darkness of his culture (think Darth Vader here – “Vader” is German/Dutch for “father”). He succumbs to the easy lure of projection – hatred of the Other – and discovers – we discover – how hate can make its own community.

In doing so, Hitler becomes a conduit for the darkest forces of the psyche and the world. As we know, he will briefly succeed in restoring a sense of destiny – and wounded innocence – in an entire nation. Max was filmed in 2001, the same year as the beginning of the “War on Terror.” I doubt if its creators had the theme of American innocence in mind, but nearly twenty years later, we would be fools, wallowing in our own denial, not to see the parallels.

Part Seven

You need chaos in your soul to give birth to a dancing star. – Friedrich Nietzsche

Re-reading this essay seven years after I first posted it, it occurs to me that Trumpus (Trump = Us) was barely a blip on the national political radar screen, a comic, low-taste character on reality TV and World-Wide Wrestling. Even two years later, the notion of him running for President would evoke laughter among us sophisticated, bi-coastal types. More or less where the idea of Hitler becoming savior of Germany was in 1919, when, in his first recorded speech, he accused the Jews of producing “a racial tuberculosis among nations.”

Just prior to that year, as Max shows us, Hitler had been in crisis (crisis: decisive point in the progress of a disease…the point at which change must come, for better or worse). He’d been wavering on the cusp of an initiatory moment, potentially open to any direction or influence. More or less where we are right now.

Hitler gave that speech just months after the end of the war, but also in the aftermath of the Spanish Flu pandemic, which he and other right-wingers blamed, predictably, on the Jews – exactly as their ancestors had done in the late fifteenth century during the Black Plague. Soon, Right-wing extremists won a greater share of the votes in those parts of Germany that suffered larger numbers of flu deaths. Researchers have found a correlation between flu deaths and right-wing extremist voting “in regions that had historically blamed minorities, particularly Jews, for medieval plagues.”

So let’s be clear about these parallels. Times of intense social change and economic uncertainty can potentially bring out the best in us. But this requires a personal courage (as Black Swan’s Nina musters) and a collective willingness to evoke, acknowledge, accept and perhaps even forgive that darkness. But the confrontation with the shadow is terrifying, and American history has provided far too many examples of precisely the opposite behavior. As I write in Chapter Eight of my book:

Between 1890 and 1920, the migration of eleven million rural people to the cities and the influx of twenty million immigrants resulted in new fears that the spiritual and physical Apollonian essence of America would be cheapened by this Dionysian element. Nativists responded by cranking up the machinery of propaganda once again. Scientists and intellectuals (including David Starr Jordan, the first president of Stanford) argued that moral character was inherited, that “inferior” southern and eastern Europeans polluted Anglo-Saxon racial purity. Woodrow Wilson, then President of Princeton, contrasted “the men of the sturdy stocks of the north” with “the more sordid and hopeless elements” of southern Europe, who had “neither skill nor quick intelligence.”

As a result, 27 states passed eugenics laws to sterilize “undesirables.” A 1911 Carnegie Foundation “Report on the Best Practical Means for Cutting Off the Defective Germ-Plasm in the Human Population” recommended euthanasia of the mentally retarded through the use of gas chambers. The solution was too controversial, but in 1927 the Supreme Court, in a ruling written by Oliver Wendell Holmes, allowed coercive sterilization, ultimately of 60,000 Americans. The last of these laws were not struck down until the 1970s.

Two years before that ruling, in Mein Kampf, Hitler praised American eugenic ideology and situated himself directly in that Anglo-Saxon (Saxony is a state in eastern Germany) tradition: “Neither Spain nor Britain should be models of German expansionism, but the Nordics of North America, who…ruthlessly pushed aside an inferior race…” After he took absolute power in 1934, Germany copied American racial and sterilization laws. After the war, at the Nuremberg trials, the surviving Nazis would quote Holmes’s words in their own defense.

I’ve speculated about the mythic and emotionally traumatic forces that created the Nazis in three other essays, The Two Great Myths of 20th Century, To Sacrifice Everything — A Hidden Life and Redeeming the world, where I write:

We don’t choose to “other” other people or groups. Othering chooses us. The need to do so seems to enter us quite early on, as parents and society gradually persuade us to identify as part of the larger tribe – to know ourselves, as the ancient Greeks implied – (but) only as we gain the absolute knowledge that we are not one of them, the others. In this modern world we are established in the first knowledge only because of the second.

I always try to make these parallels clear between mythic or historical themes and our current conditions, but it’s hard to keep up with Trumpus, who is constantly upping the ante of hate and ignorance. As I finish this re-write, he praises the “bloodline” of the eugenicist and racist Henry Ford, threatens to enact absolute power against the media and encourages police violence against anti-racist protestors.

Circular craziness: American racists influenced Hitler’s thinking in 1920, and his life, despite what happened to Europe, became a model for our American fascists of 2020. For a clear summary of early eugenicist rantings and their influence on the “alt-right” Trumpus supporters and political provocateurs of today, read here.

Black swans and white vultures: I originally titled this essay, “A Black Swan and a White Madmen.” But it now seems that I need a more poetic counterpoint to “black swan” that includes all the fascist madmen of the past hundred years. Neither “eagle” nor “wolf” fits. So I settled on “vultures”, which circle above, out of danger, around dying animals – or cultures – and swoop down to eat them once they can no longer defend themselves.

Actual vultures may not be white, but their metaphorical human equals certainly were and are. It is the time of disaster capitalism, in which financial elites exploit national and international crises to further centralize wealth while citizens are too weak or distracted to resist. It’s the time of vulture funds, which prey on debtors in financial distress by purchasing cheap credit on secondary markets to make a large monetary gains and leave the debtors in a worse state. It’s the time of housing vultures, which sucker millions out of their homes for quick profit. It’s the time of hedge fund managers like Martin Shkreli — the “Pharma Bro” —  who buy the patents of critical drugs and raise their prices by factors of over fifty. It’s the time of the second Gilded Age, as I write here.

who buy the patents of critical drugs and raise their prices by factors of over fifty. It’s the time of the second Gilded Age, as I write here.

The year 2020 is not yet half finished. In three months, forty million have lost jobs and medical insurance (on top of those millions who had already given up searching for jobs and the forty million who already had no health insurance), and the nation’s billionaires have seen their collective wealth increase by nearly half a trillion dollars.

But we mythologists are always searching for the reframe. Otherwise, there is no point in studying myth. We’re always trying to imagine how a soul – or the soul of a culture – might behave in a world that provided real mythic narratives, genuine ritual containers and elders or mentors who could see the potential that can’t be seen on the ordinary surface of things. The poet Theodore Roethke wrote: “In a dark time the eye begins to see.” Nina’s struggle to become who she is supposed to be – and in the process, to integrate her shadow and make her art – offers us hope in this dark time. Toward the end of my book I write:

Now we are called to remember things we have never personally known, to remember what the land itself knows, that which has been concealed from us by our own mythologies. We have the opportunity to remember who we are, and how our ancestors remembered, through art and ritual…Our task is unique: inviting something new, yet familiar, to re-enter the soul of the world…

“Hope is reborn each time someone awakens to the genuine imagination of their own heart,” says Michael Meade…imagination builds a bridge between fate and destiny. We need to use sacred language, in the subjunctive mode: let’s pretend, perhaps, suppose, maybe, make believe, may it be so, what if – and play. This “willing suspension of disbelief” is what Coleridge called “poetic faith.”

What if Hitler had successfully channeled his trauma into art, as Nina does? What if some form of communitarian, egalitarian or anarchist organization of society had prevailed in 1920s Germany? What if such a society had provided a non-authoritarian alternative to Soviet collectivism? What if Americans had seen such activity as a positive model and rejected their heritage of fear of the Other, brutality toward the weak and hatred of their own bodies?

What if you were to add your own prayers for the possible right here and now?

What if we were to consider (consider: “with the stars”) the stories that the mega-rich have been telling themselves about themselves and invite them to re-imagine those stories? What if we remembered that actual vultures and similar scavenger birds are necessary for healthy ecosystems, doing the dirty work of cleaning up after death, helping to keep ecosystems healthy and preventing the spread of disease, all so that new, healthy life may emerge?

What if we imagined a culture that perceived every single human being in terms of what innate gifts they came into the world to offer? What if, despite the traumas of racism and gender stereotyping, all of us could become who we were meant to be?

To close, I invite you to watch an interview with an extraordinary person I briefly knew  years ago. His Name? Gryphon Blackswan.

years ago. His Name? Gryphon Blackswan.