Part Five

Historian Milton Viorst writes that the theme of the 1950s was “security: internal security (McCarthy), international security (massive retaliation), personal security (careerism). And yet no one felt secure.” Other factors would come later: Civil Rights and Viet Nam, which provided the focus for dissent; and the birth control pill, which allowed women independent sex lives.

Other factors would come later: Civil Rights and Viet Nam, which provided the focus for dissent; and the birth control pill, which allowed women independent sex lives.

Another factor had always existed: the need to identify as an initiatory group, to go through the rites of passage not as individuals but together. America was poised unstably between its Puritan heritage and the hedonism of the consumer lifestyles.

Imagine America entering the liminal period of 1953-1955. Imagine it as a time during which the empire reached its apogee (the current madness being merely a last gasp), when the seeds of its collapse first sprouted. The U.S. had a position of security unparalleled in history, controlling the Western Hemisphere and both oceans. Its economy and culture dominated the world. And yet anticommunist hysteria was running wild.

In April 1953, President Eisenhower barred gays from all federal jobs. In June, the government executed the Rosenbergs. The Korean War ended in July, just as the Cuban revolution began.  In August, the C.I.A. overthrew Iran’s government. Kinsey’s book on female sexuality appeared in the fall. The film War of the Worlds left viewers staring fearfully at the stars, while Shane presented the lone Hero literally riding off into the sunset. In December Playboy’s first issue, featuring Marilyn Monroe, arrived.

In August, the C.I.A. overthrew Iran’s government. Kinsey’s book on female sexuality appeared in the fall. The film War of the Worlds left viewers staring fearfully at the stars, while Shane presented the lone Hero literally riding off into the sunset. In December Playboy’s first issue, featuring Marilyn Monroe, arrived.

In May 1954, the French surrendered at Dien Bien Phu in northern Viet Nam. Ten days later, the Supreme Court decided Brown vs Board of Education. In June, Congress added the words “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance, and the C.I.A. overthrew the Guatemalan government. Three days later, Viet Nam was officially divided. In August, as the C.I.A. defeated the insurrection in the Philippines, Congress banned membership in the Communist Party.

Rebel Without A Cause opened in early 1955. In July, “In God We Trust” became mandatory on all currency. The Soviets detonated their first H-bomb in August. Allen Ginsburg first recited Howl in October. In December, shortly after Emmett Till’s murderers were acquitted, Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat to a white person.

And one other thing: in July 1954, Elvis Presley released his first record.

America was entering a period of continuous change from which it has never recovered. The spark that set things off occurred when southern whites first blended country music and blues, just as the civil rights movement was making its move and all Americans were scrambling to acquire televisions. Most critically, Elvis emerged from the darkness of the deep South.

Soon, television was showing white men performing like blacks, men who were comfortable in their bodies and defiantly, humorously, ambiguously sexual, men who challenged John Wayne’s code of masculinity. Stephen Diggs calls this the blues revolution: “Dionysus is inciting the instinctual maenads to pull Pentheus from the treetop back down to earth and then tear his detached vision to bits.” To Michael Ventura this was “… one of the most important moments in modern history.” Eldridge Cleaver wrote,

… contact, however fleeting, had been made with the lost sovereignty – the Body had made contact with its mind – and the shock…sent an electric current throughout this nation.

It was the incursion of the Dionysian mode into a culture that had long been ruled by a poor version of the Apollonian. In contrast to “containment,” the theme that dominated so much of public life, youth became enthusiastic (“en-theos,” taken over by the god of ecstasy). Quickly, the nature of western dance and performance changed. And along with the released energies came much more.

The music sparked a collective flame; within a very few months the youth market exploded. More importantly, a youth movement began to spread across the world. For perhaps the first time, an entire generation saw the world in fundamentally different terms from its parents and chose to define itself as separate. Unknown to them, the only models for this phenomenon in all of history had been the groups of young men going into the liminal madness of initiation together. There are accounts of African boys dancing before the elders’ huts, demanding to be initiated. Now white girls (who individually might have been timid and obedient) were forming mobs, breaking through police lines to approach their Dionysian priests, trying to “dismember” them as the Maenads had done with Pentheus. One of Elvis’s musicians recalled:

I heard feet like a thundering herd, and the next thing I knew I heard this voice from the shower area…several hundred (girls) must have crawled in…Elvis was on top of one of the showers…his shirt was shredded and his coat was torn to pieces…he was up there with nothing but his pants on and they were trying to pull at them up on the shower.

Chapter Four of my book takes a long look at the idea known as the “return of the repressed,” from both psychological and mythological perspectives, and it projects it outwardly toward the cultural and the political. By now, you shouldn’t be surprised that the mythic figure who mediated this process for hundreds if not thousands of years was Dionysus. Every night, in taverns across the world, people (mostly men) participate in a certain kind of eucharist, taking the god into their bodies in the form of Lusios, the Loosener, often with the conscious intention that he will facilitate conviviality (from convivere “to carouse together, live together”) and honest conversation (to turn together).

But the god, they all know, is fickle. Imbibing too much may provoke a deeper, unintentional honesty and even the violence we normally associate only with the Other. But in America, Dionysus is the Other, and when he returns from long years in the realm of the repressed, he may not be so convivial.

In the 1950s the madness broke out as the return of both erotic excitement as well as (in a few years) profound rage, signaling the opening of the gates through which all of the culture’s repressed energies would flow. But there were few elders to guide and welcome the young bacchants, because now it was the elders themselves against whom the youth were rebelling. The result was – for fifteen years, and perhaps for the first time in history – an international community more or less in agreement about a broad number of issues, the most central of which was a mythological insight. This world was no longer being ruled by Ouranos, but by his son Kronos. This was a world of fathers who were killing their children.

In 1960, well before the antiwar protests began, 50,000 Americans demonstrated for civil rights, with 3,600 arrests. For white students, this activism marked their first connection to the Other as well as the direct (if temporary) experience of otherness. Many felt more commonality with young black and brown people than with their parents. Children of the slaves were mixing with children of the masters.

That summer “the Twist” burst upon the scene, “a guided missile,” wrote Cleaver, “launched from the ghetto into the very heart of suburbia,” succeeding as politics couldn’t do in helping whites reclaim their bodies.  Getting up and dancing individually or in groups broke down the traditional Western barrier between performer and immobile audience. It meant a revival of a participatory process rooted ultimately in ecstatic, pagan religion that had been repressed for centuries. And, since dancers stopped holding hands, it meant that girls didn’t have to follow anymore.

Getting up and dancing individually or in groups broke down the traditional Western barrier between performer and immobile audience. It meant a revival of a participatory process rooted ultimately in ecstatic, pagan religion that had been repressed for centuries. And, since dancers stopped holding hands, it meant that girls didn’t have to follow anymore.

The same collective urge that gave rise to the Twist also propelled John Kennedy into office and evoked new idealism for millions. Consequently, youth took his death particularly hard. It is no coincidence that a new form of maenadism – “Beatlemania” – erupted only two months later. Barbara Ehrenreich writes, “At no time during their U.S. tours was the group audible above the shrieking.”Susan Douglas argues that the resonance between Kennedy and the Beatles allowed for “a powerful and collective transfer of hope.”

Part Six

…our fire, our elemental fire

so that it rushes up in a huge blaze like a phallus into hollow space

and fecundates the zenith and the nadir

and sends off millions of sparks of new atoms

and singes us, and burns the house down. – D. H. Lawrence (“Fire”)

What makes the engine go?

Desire, desire, desire.

The longing for the dance stirs in the buried life.

One season only, and it’s done. – Stanley Kunitz (“Touch Me”)

Yes, their – our – parents had plenty of needs and wants, which they believed they were satisfying by buying, accumulating, getting ahead (that most characteristic description of the American ideal of progress) – and moving up:  from the assembly line to the corner office, from the Baptists to the Episcopalians, and of course from the apartments to the split-level houses, where they could show off (in those huge, energy-leaking, suburban front windows, with those new gas-guzzler cars freshly washed, parked in the driveways rather than the garages).

from the assembly line to the corner office, from the Baptists to the Episcopalians, and of course from the apartments to the split-level houses, where they could show off (in those huge, energy-leaking, suburban front windows, with those new gas-guzzler cars freshly washed, parked in the driveways rather than the garages).

But desires? The culture of consumption was displacing the Puritan heritage and the Paranoid Imagination, but only in the most superficial manor. What they had and were repressing was destined to emerge among their children.

Someone dancing inside us has learned only a few steps:

The “Do-Your-Work” in 4/4 time, the “What-Do-You-Expect” Waltz.

He hasn’t noticed yet the woman standing away from the lamp.

The one with black eyes who knows the rumba

And strange steps in jumpy rhythms

From the mountains of Bulgaria.

If they dance together, something unexpected will happen;

if they don’t, the next world will be a lot like this one.

– Bill Holm (“Advice”)

The ecstatic experience of dancing to rock music, with or without chemical stimulation, evoked a desire for other non-material ways of knowing. It helped to define this community of initiates,  who soon shared a fascination with both the introspection offered by psychedelics and the easy, if fleeting, access that drugs provided to communitas. For a few years, millions of young people commonly distinguished between those who opposed the war, got high, listened to rock, wore long hair and rejected the Puritan Ethic, and those who didn’t. Or: between Dionysian ecstasy and Apollonian rationality. Or: between authentic and contrived innocence.

who soon shared a fascination with both the introspection offered by psychedelics and the easy, if fleeting, access that drugs provided to communitas. For a few years, millions of young people commonly distinguished between those who opposed the war, got high, listened to rock, wore long hair and rejected the Puritan Ethic, and those who didn’t. Or: between Dionysian ecstasy and Apollonian rationality. Or: between authentic and contrived innocence.

Many attempted to reclaim that innocence in rural communes. Whether it was in those pastoral images or in urban circuses like Haight-Ashbury, the rebellion drew its power from its negation of the bland conformism of suburbia. But the phrase, “Don’t trust anyone over the age of thirty!” revealed a profound grief about the loss of elderhood. Adults could not initiate youth into a meaningful world because they had never been initiated themselves.

But, said Bob Dylan, the sensation of first hearing Elvis as a teenager was “like busting out of jail.” All the issues repressed by the culture for so long erupted into the open. Millions marched against the war, not merely because it was a mistake bred of good intentions (as even liberal apologists still contend), but because it was nothing other than mad, imperialist genocide.

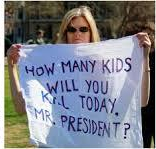

The parents, blinded by their mythologies, could not see what was obvious to their children.  The generation that had survived the Depression, saved Europe from the Nazis and gratefully consumed the myth of American innocence could only sputter, “My country, right or wrong!” The youth, however, who always see the mythic issues more clearly, responded: “Hey, hey, LBJ! How many kids did you kill today?”

The generation that had survived the Depression, saved Europe from the Nazis and gratefully consumed the myth of American innocence could only sputter, “My country, right or wrong!” The youth, however, who always see the mythic issues more clearly, responded: “Hey, hey, LBJ! How many kids did you kill today?”

Civil rights agitation sparked movements for the liberation of women, Latinos, farm workers, Indians, gays, prisoners, the disabled, the environment, the body – and the soul. Thousands discovered that psychedelics hinted at spiritual realms that conventional religious leaders could never understand and indeed were staunchly opposed to. Eventually, millions would investigate natural foods, the human potential movement and Eastern religion.

Then the reaction set in, as I write in Chapter Eight of my book:

By 1970, the white middle class was exhausted, disenchanted and vulnerable to backlash. Hollywood responded with vigilante movies starring Charles Bronson and Clint Eastwood in which lone redeemer-heroes cleaned up the urban chaos.

Working-class whites had struggled so hard to achieve their Dream, only to hear radicals condemning their patriotism and materialistic lifestyles. They retreated into willful ignorance and innocence. Forty-nine percent of the public simply refused to believe that the shameful massacre at My Lai (not to mention dozens of other such events) had occurred. If American boys actually acted in this manner, then once again America was no different from any other nation.

…When the National Guard exploded at Kent State in 1970, writes (Milton) Viorst, many local people were outraged at the students, not the killers, and rejoiced that, “…the act had been done at last… the students deserved what they got.”

“The act” was mythic, ritual sacrifice of the children. So many youth had rejected American values so completely that they had seemingly become Other. Although America had been slaughtering children in Viet Nam and in the ghettoes for years, the message was unmistakable: You will be like the fathers or die.

Shortly after Kent State, as students struck on 450 campuses, thugs attacked demonstrators and police watched approvingly. Years later, after exonerating the students, Kent State commissioned a monument. However, it rejected sculptor George Segal’s model of Abraham poised with a knife over Isaac. It would not accept the mythic implications of the murders.

The myth of American innocence had weathered many shocks, but its stereotype of the internal Other had survived. By this point, the paranoid white imagination no longer saw African Americans as long-suffering, non-violent citizen-saints. They were now dashiki-wearing, afro-haired, foul-mouthed terrorists, “black panthers” who ruled the city at night (curiously, in Greek iconography, the panther was one of Dionysus’ animals).

The projection of American Dionysus was nearly back where whites needed it, but not quite. In the next ten years, the F.B.I. would make sure that most black, red and brown activists were discredited, imprisoned or (in over two dozen cases) dead. Black rage turned inward, in drug addiction and gang violence. In 1981, Hollywood bestowed its cultural approval by releasing Fort Apache the Bronx. The film’s title acknowledged a hideous mix of mythic and racial stereotypes. A beleaguered police station stood as a small outpost of civilized values within a wilderness of black and brown savagery.

With the end of the Viet Nam War, the central focus for activism disappeared. “The music died,” as Don McLean sang. Culturally and politically, the tenuous connection between rebellion and pleasure began to open up. Perhaps, since rock (unlike its parent, the blues) is the musical expression of uninitiated young men, this was inevitable. The coalition broke up into its constituent parts: a few violent revolutionaries; apolitical mystics; and minority activists.

As idealism collapsed into consumerism, the youth movement receded back into the youth market. Critics now debate whether commercial youth culture is deliberately created in order to separate youth from their families, recreating them as vulnerable consumers, or whether, as Simon Frith writes, their real needs “– to make sense of their situation, to overcome their isolation – are dissolved in a transitory emotional moment.”

From a pagan or indigenous perspective, youth do indeed have innate needs. Each generation needs to briefly separate out and endure the initiatory fires under the capable guidance of elders, to return, to be welcomed back, and then to re-imagine the world. But as they aged, millions succumbed to narcissistic self-absorption, cynicism or fundamentalism. The youth market, now controlled almost completely by a few mega-corporations, exists only to exploit and channel the occasional eruptions of Dionysian energy. The counterculture ended, writes Ehrenreich, “by affirming the… materialistic culture it had set out to refute.” Rock and its descendants are now little more than the background music to new frenzies of consumerism — and nationalism. “The sixties,” writes Camille Paglia, “never completed its search for new structures of social affiliation…‘do your own thing’ encouraged individualism but produced fragmentation.”

Decades later, musical preference still expresses identity. But now it distinguishes between youth populations, rather than defining a community separated from their parents by a generation gap. Ronald Reagan co-opted Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the USA.” Beer and car companies sponsor tours by musicians; loudspeakers in Afghanistan played “We will rock you!” as the bombers took off; CIA torturers blasted Heavy Metal into prisons to disorient prisoners; Jimmie Hendrix’s “Voodoo Child” is played at boot-camp initiations; skinheads sell racist rock over the Internet; and misogyny drives much of Hip Hop. The volume increases as civic involvement declines.

Meanwhile, observes sociologist Orlando Patterson, America’s image of the Other has expanded to include aspects of which whites are now admittedly, nervously envious: “The Afro-American male body – as superathlete, as irresistible entertainer…as sexual outlaw, as gangster.” Black athletes and entertainers attract a mainstream culture that is over-balanced toward Apollonian demands. In this context, he says that African-American images have become a “Dionysian counterweight” unstably balanced with the discipline required of those who must tolerate the conditions of the modern workplace. Dionysus has free reign in the inner cities, where he remains safely contained, “…until the instinctual need for release from the Apollonian pressures…calls for its tethered, darkened presence.”

Blacks now provide much of the cultural container that allows white, male youth (who purchase seventy percent of Hip-Hop) to act out some mild rebellion between their suburban school years and the corporate life they must eventually submit to. All learn to suppress their innate grandiosity of soul and project it onto celebrities. Instead of living creative lives as involved citizens, we consume the cultural products, including Dionysus, that the media offer us.

Generally, however, we watch the Dionysian experience, like Pentheus in his tree spying on the maenads. Popular culture apparently assumes that blacks have a certain license to behave in ways the culture as a whole chooses to repress. Some blacks play along for profit while others, writes historian Gerald Early, resent “the entrapment of sensuality we are forced to wear as a mask for the white imagination.”

Meanwhile, Hip-Hop subculture reflects our most fundamental myth, the sacrifice of the children, back toward the wider culture.  It displays anger and self-confidence in the lyrics, but grief and depression in the imagery: baggy pants, drooping below the waste; everything collapsed. Adolescents, especially minorities, are well aware of being forced to carry the weight of the world that their parents will not.

It displays anger and self-confidence in the lyrics, but grief and depression in the imagery: baggy pants, drooping below the waste; everything collapsed. Adolescents, especially minorities, are well aware of being forced to carry the weight of the world that their parents will not.

However, the memory of that tentative healing of the mind-body split survives, and Americans now commonly acknowledge a desire for authenticity that was birthed in the 1960s. Whether they search for it in rock or gospel music, meditation, hiking, gardening or cocaine is, to an extent, irrelevant. The genie is out of the bottle; even commercials commonly hint that we are capable of so much more. Despite their implication that only “stuff” will satisfy their longing, many baby boomers and their children still carry an idealism that counters the prevailing cynicism and fear. And the energy, the desperate, if unconscious craving for initiation, is as strong as ever. The creative imagination openly opposes the culture of innocent violence and violent innocence.

Whether through the calm attention of Yoga, natural foods and body therapies or through the ecstatic release of popular music and the discipline of fitness programs, Americans have begun the long pilgrimage back into the body. It is no coincidence that these revolutions have occurred simultaneously with the emergence of blacks and gays out of the national underworld. Slowly, painfully and generously, people of color and unconventional sexuality have offered white America the opportunity to pull back its projections from the Other. Coming down out of our heads and remembering the body’s demands, we encounter the needs of the soul. We encounter desire.

The madness is still at the gates. Michael Ventura, in another essay, argues that, for better or for worse, successive generations of youth have spontaneously produced “…forms – music, fashions, behaviors – that prolong the initiatory moment.” A period that in the tribal world lasted only a few weeks has now been extended into decades. The pace of change has kept millions in a state of ongoing liminality throughout our entire lives.

But if we reduce such phenomena to psychology or see only eternal adolescents duped by consumer culture, we are missing the point. We have all become initiates, without being welcomed home, stuck in the middle of a great transition. In some parts of the Third World, literally half the population is composed of teenagers, crying out to be seen. This is tragic, but it is also our best hope for renewal. “Hence their demand – inchoate, unreasonable and irresistible – is that history initiate them.”

Yes, but what about Elvis?

Part Seven

Elvis Presley is the greatest cultural force in the twentieth century. – Leonard Bernstein

But what about Elvis? How do we understand that 32 years after his death (when I did the research for my book), 44 countries were hosting some 525 fan clubs, and an Elvis search engine had 330 sites with over 500 books, or that fans continue to refer, humorously or not, to an “Elvis religion”? We cannot explain this away, because we are in the realm of mystery, where images are our only guides and questions are more important than answers.

Would someone else have created the same reactions? Of course, there had been and were countless talented black performers, and later, many whites. Some of these artists were and are carriers – channelers – of the most profound energies of the Earth, of duende. But it was Elvis. All we can say is that the soul of the world needed someone like him at that particular moment, an “animus man,” in Pinkola-Estes’ words, “one who acts out the unrealized soulfulness of others.”  The collective consciousness dreamed up his image to carry a positive projection of Dionysus to counter the long centuries of marginalization. As in the ancient Athenian festival of the Anthesteria, the god was finally being invited to enter the gates of the city.

The collective consciousness dreamed up his image to carry a positive projection of Dionysus to counter the long centuries of marginalization. As in the ancient Athenian festival of the Anthesteria, the god was finally being invited to enter the gates of the city.

His art had roots in Africa, where everything originates in ritual. Although colonialism and oppression had broken down and denatured those forms, a physical energy and a wisdom that questioned the assumptions of western culture still came through. Segregationists rightly perceived that this “Devil’s music” would corrupt their children. What were they so afraid of? The simple answer is the threat of miscegenation.

On a deeper level, Elvis was questioning the image of the black American Dionysus, first among Americans and then, via television and movies, across the world. If a white man could carry such archetypal energy, then anyone could. Now consider what a threat he was. If anyone could claim this heritage of our “indigenous mind” – a mind that has reconciled with the body – then America no longer needed to demonize that mind, no longer needed to project it upon black people. And if that were to happen, then the whole edifice of American myth and American capitalism might collapse of its own foul mass of contradictions.

But the work of the soul is to move past contradiction into true paradox, to hold the tension of the opposites. Elvis reveled in paradox. His images, writes Erika Doss, were “a tangled hybrid of fact and desire.” His voice dissolved racial boundaries, and his obvious bodily comfort questioned gender norms. He was, wrote critic Marc Feeney, “astonishingly beautiful.” He had charisma (“favor, divine gift” Charis was the name of one of the three attendants of Aphrodite).

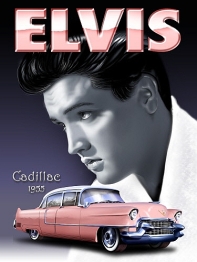

Perhaps more importantly, a man (at least a white man) had never seemed so loose. He wore mascara and wild clothes in wilder colors to exaggerate this ambiguity, and he drove a pink Cadillac.  One critic described his onscreen persona as “aggressively bisexual in appeal.” Another placed the “orgasmic gyrations” of the title dance sequence in (the film) Jailhouse Rock within a lineage of cinematic musical numbers that offer a “spectacular eroticization, if not homoeroticization, of the male image.” A third wrote that he was “an ambivalent figure who articulated a peculiar feminized, objectifying version of white working-class masculinity as aggressive sexual display.”

One critic described his onscreen persona as “aggressively bisexual in appeal.” Another placed the “orgasmic gyrations” of the title dance sequence in (the film) Jailhouse Rock within a lineage of cinematic musical numbers that offer a “spectacular eroticization, if not homoeroticization, of the male image.” A third wrote that he was “an ambivalent figure who articulated a peculiar feminized, objectifying version of white working-class masculinity as aggressive sexual display.”

Offstage he was exceedingly polite; onstage he was sullen, defiant and self-mocking. Singing both rock and gospel, he straddled the boundaries of sacred and profane music. He combined small-town values and an astonishing, urban energy. In a sense, he was both mortal and immortal, like Dionysus and the other suffering gods before him. Tim Riley writes that compared with John Wayne’s image of masculinity, Elvis was “…more complex, more open to change, less fixed on a single idea or attitude.” He personified liberation and transgression, and his clear affront to the bourgeois world gave teenagers permission to follow. Like Johnny Appleseed, wrote Cleaver, he “sow[ed] seeds…in the white souls of the white youth.”

But he also embodied transformation. As such, from his position at the border between the worlds, he beckoned especially to women, inviting them into Dionysian ritual – the madness, the pharmakon – that is both cause and cure of itself. This archetypal energy has the potential to transform the individual, the community and the nation into who or what we actually came into this world to be – but only, as in his myths, by dismembering one’s entire conception of what or who one is. As Karl Marx said, “all solid melts into air.” Elvis was the first to propose the great transformation.

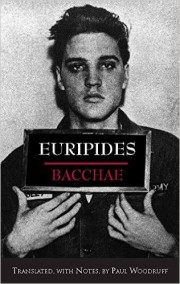

The publishers of a 1998 translation of The Bacchae made this insight abundantly clear by putting Elvis’ photo, rather than a classical image, on the cover. And it wasn’t just any picture of him; it was his army induction photo. As in the play, Dionysus was (temporarily) in prison.

The publishers of a 1998 translation of The Bacchae made this insight abundantly clear by putting Elvis’ photo, rather than a classical image, on the cover. And it wasn’t just any picture of him; it was his army induction photo. As in the play, Dionysus was (temporarily) in prison.

What are the other mythic images here? James Hillman taught that in classical myth, the gods rarely appear alone; their stories interweave:

Each cosmos which each god brings does not exclude another; neither the archetypal structures of consciousness nor their ways of being in the world are mutually exclusive. Rather, they require one another, as the gods call upon one another for help.

Commentators in the 1960s insisted on the Oedipal sources of the generation gap. But if young people dreamed of patricide, it was directed against Kronos’ insatiable appetite for his own children, and it was driven by a sense of betrayal. After all, hadn’t oracles warned Ouranos, Kronos and Zeus that their children would overthrow them? Isn’t that fear at the root of the patriarch’s reign of terror? Two myths intersected in the 1960s. The universal dream of the hero’s journey collided with a nightmare, the refusal to anoint the new kings and queens of the world. Youths demanded initiation and meaning, while elders offered the false choice of either stultifying conformity or literal sacrifice.

Americans were enacting other myths as well. In one story, the craftsman god Hephaestus vented his rage against Hera by imprisoning her in a golden chair. Perhaps he had been confining women on the “pedestal” of patriarchy? Only Dionysus could loosen him up, getting the lame god drunk and teaching him to dance, after which Hephaestus released Hera and married Aphrodite. Aphrodite! The madness of Dionysus brought the cure. Pentheus, by contrast, retreated into a masculinity so brittle that Dionysus could effortlessly crack it and release the repressed feminine energies that eventually overwhelmed him. For more on this theme, see my blog series “Male Initiation and the Mother in Greek Myth.”

This is Elvis’ mythic significance. A unique combination of talent, ambition and overdue cultural changes waiting to be sparked created an icon. He became both a gatekeeper and a role model who loosened the boundaries of the American ego. Perhaps it would be better to speak of “the” Elvis – like “the” Christ – since his personal life is far less important than the role he embodied. One writer has argued that Jim Morrison was a conscious, thus more appropriate, carrier of the Dionysian role in America. But he appeared ten years after Elvis had already broken down the walls.

Archetypes demand to appear in their fullness, especially when we avert our gaze from their darker sides. Perhaps without Christ’s advent as a pure god of love, there would have been little need for the Western world to imagine Satan. Similarly, because millions projected only the savior image upon Elvis, he had to live out both sides of the old story. Within the Christian framework of American myth, many saw his death as a sacrifice for the world rather than as enacting renewal of the world. As with the Catholic saints, his devotees give ritual attention to his death date, not to his birthday.

Elvis, writes Pinkola-Estes, became the focus of the cultus of the dying god, “a drama in which a dried out culture requires the blood sacrifice of the king in order to…rebuild itself.” In the symbolic world, he joined the eternal scapegoats Osiris, Dionysus and Jesus.  Another book cover shows a man wearing an Elvis tattoo with the words “He Died For Our Sins.”

Another book cover shows a man wearing an Elvis tattoo with the words “He Died For Our Sins.”

(Religious literalists please take note: the pagan imagination encourages humor. It makes absolutely no difference to his fans if such gestures are serious or tongue-in-cheek.) In this context, his suffering, his drug-addict death and his failure to find happiness made him even more attractive to his fans. He was, so to speak, one of us.

Many of his fellow “looseners” (James Dean, Marilyn Monroe, Jimi Hendrix, Morrison, Janis Joplin) died before Elvis; yet the mold had been cast in his image in 1955. Since then, many others who couldn’t hold the fullness of the archetype have followed him to the underworld. Allen Ginzburg, Timothy Leary and Ken Kesey played the loosener role with somewhat more balance. Still others (Jim Jones, Charles Manson and David Koresh) literalized the darkest of Dionysus’s masked roles, leading crazed maenads on murderous rampages.

Nevertheless, Elvis has achieved immortality; in 2007 his estate earned $40 million. He remains as popular in death as in life because he served in a very real sense as America’s initiator. Ventura concludes, “It is not too much to say that, for a short time, Elvis was our ‘Teacher’ in the most profound, Eastern sense of that word.”

Religion is much more complex than we can imagine. Humorous “Elvis churches” thinly mask the inarticulate but broad conviction that some god descended and resided briefly among us. Doss argues that Americans mix and match their beliefs and practices, that his veneration is a “strong historical form of American religiosity.” Consider the vast array of relics at and pilgrimages to his sacred shrine. After the White House, Graceland remains the most popular house tour in the country, drawing over 750,000 visitors yearly. In 1997, on the twentieth anniversary of his death, 60,000 fans came, and 10,000 stood all night at his grave. Consider the many Elvis “sightings,” as if he never died — or that he had returned.

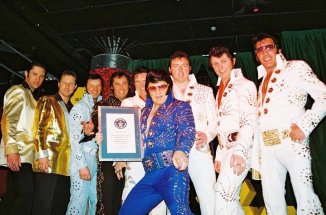

Finally, consider the thousands of impersonators who, as in the Imitatio Christi,  devote their lives to him every night in nightclubs (his ritual containers) in almost every country. According to Gael Sweeney, “true” impersonators believe that they are “chosen” by The King himself to continue his work and judge themselves and each other by their “authenticity” and ability to “channel” his essence. Several radio stations feature Elvis impersonator material exclusively. In 2014, 37 years after his death, 895 impersonators gathered at a North Carolina resort to pay tribute.

devote their lives to him every night in nightclubs (his ritual containers) in almost every country. According to Gael Sweeney, “true” impersonators believe that they are “chosen” by The King himself to continue his work and judge themselves and each other by their “authenticity” and ability to “channel” his essence. Several radio stations feature Elvis impersonator material exclusively. In 2014, 37 years after his death, 895 impersonators gathered at a North Carolina resort to pay tribute.

Let’s take this one step deeper and imagine a story that begins to move an entire culture. The Bacchae tells us that Dionysus descended to Hades and raised his mother Semele to the divine community of Heaven. Similarly, let’s imagine that while the spirit of feminism was veiled in America, young Elvis descended to its underworld, Memphis’s black ghetto, where he discovered the blues.

The blues had power (and danger) because it tapped into the soul’s depth, where extremes of joy and grief meet each other. Hillman writes:

In Dionysus, borders join that which we usually believe to be separated by borders…He rules the borderlands of our psychic geography. There, the Dionysian dance take place; neither this nor that, an ambivalence – which also suggests that, wherever ambivalence appears, there is a possibility for Dionysian consciousness.

Elvis become a conduit for that terrible beauty. Was there some kind of terrible initiation? What did the black musicians of Memphis see in him? (We recall that Jerry Lee Lewis and televangelist Jimmy Swaggart are cousins). Then he emerged into the light (the spotlight) precisely at America’s initiatory moment.

And unknowingly, he brought guests with him – the Goddess, and the beginning of the long memory. His eroticism, writes Doss, encouraged girls “to cross the line from voyeur to participant…from gazing at a body they desired to being that body.” Abandoning control – screaming and fainting, and eventually choosing to be sexual on their own terms – was the beginning of their revolution, long before feminism became a political movement. She quotes one woman: Elvis “…made it OK for women of my generation to be sexual beings.”

This was not the first time that American girls had gone crazy about a male singer. Ten years before Elvis, thousands of them, according to Time Magazine, had been in “a squealing ecstasy” at a Frank Sinatra concert. But Sinatra was not one to swivel his hips; he was a crooner, not a rocker. And besides, the war was still raging. The time simply hadn’t been right.

Ten years later, it became apparent that millions of girls had both deep longings and deep pockets. Quickly, the music industry responded with “girl groups.” By the early sixties, this was the one area in popular culture that gave voice to their contradictory experiences of oppression and possibility. It encouraged girls to become active agents in their own love lives. By allying themselves romantically and morally with rebel heroes, they could proclaim their independence from society’s expectations about their inevitable domestication. And even when the lyrics spoke of heartbreak and victimization, the beat and euphoria of the music contradicted them.

And the music was made by groups of girls. It was, writes Susan Douglas, “a pop culture harbinger in which girl groups, however innocent and commercial, anticipate women’s groups, and girl talk anticipates a future kind of women’s talk.” If young women could define their own sexual sensibility through popular music, couldn’t they define themselves in other areas of life? Another woman claims, “Rock provided…women with a channel for saying ‘want’…that was a useful step for liberation.” Douglas argues that “…singing certain songs with a group of friends at the top of your lungs sometimes helps you say things, later, at the top of your heart.”

The limping Hepheastus released Hera from the golden chair, with the help of Dionysus. One might argue that in the 1970s, men (unaware of their own limps) released women from the pedestal of ideal womanhood. In fact, women destroyed that golden prison themselves. Clearly, feminist demands for autonomy, equality, safety and choice were long overdue. But American women were also the first to elucidate the new (or remember the old) thinking that may inspire fundamental change at the mythic level, even if such changes happen with glacial slowness.

Cynthia Eller writes that feminism began asking why little girls had to wear pink and big girls had to wear high heels, but it “…segued naturally into one that asked why God was a man and women’s religious experiences went unnoticed.”

The women’s spirituality and pagan movements – and later, the men’s mythopoetic movement – were all outgrowths of secular feminism, which in turn had been catalyzed in that 1954 initiatory moment. Catalyze: from cata (downward) + lyein (to loosen, also the root of Lusios, Dionysus the Loosener).

Is it a stretch to suggest that this moment — some 437 years after Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-five Theses to the door of a German Cathedral and began the Protestant Reformation, some 213 years after Jonathan Edwards proclaimed the First Great Awakening — was the beginning of a religious movement that might eventually usher in a new story to replace the Myth of American Innocence? Leonard Bernstein claimed that Elvis was the greatest cultural force of the twentieth century. Did Elvis lead us to the re-awakening that may re-animate and re-sacralize the world?

Perhaps that is a bit grandiose. But Dionysus asks us just how much reasonable, dispassionate discourse has achieved. “You have tried prudent planning for long enough,” says Rumi. “This is not the age of information,” writes poet David Whyte,

This is the age of loaves and fishes,

People are hungry,

And one good word is bread

For a thousand.

Here are my other essays on race in America:

— The Mythic Sources of White Rage

— Affirmative Action for Whites

— The Sandy Hook Murders, Innocence and Race in America

— Hands up, Don’t shoot – The Sacrifice of American Dionysus

–– Do Black Lives Really Matter?