Spiritual and mystical literature often speaks of the need to pay full attention, to be present moment to moment. In addition, what we might call “soul-work” asks us to focus our awareness of both the outer and the inner worlds with a detached, witnessing perspective, even while, as Joseph Campbell wrote, “participat(ing) joyfully in the sorrows of the world.”

A large part of the self is normally hidden from us. Indeed, cognitive linguist George Lakoff claims that only five percent of our thinking is conscious. So paying attention (attention: from the Latin, “to stretch”) forces us into the awareness of infinite complexity and mystery. Resisting the temptation to resolve the big questions of life into simple, black-white dualities – the legacy of monotheistic thinking – we hold the tension of the opposites. Otherwise, we risk a disruptive return of the repressed.

Most people throughout history have not become yogis meditating in caves. Far more have chosen the way of the indigenous, creative imagination: turning life’s tragic contradictions and impossible choices into the images of art.

But what about social groups? Is it necessary or even possible for an entire society to hold that kind of attention, if only for a brief but intense period of time, to acknowledge the presence of its own shadow? Communities cannot enter psychotherapeutic relationships; they can only approach the unconscious through communal ritual within a broad mythic container.

In highly structured societies, such as classical Athens, that emphasize logic and rational thinking, the shadow is the unreasonable, violent and uncontrollable force of natural life. Like the ivy plant in a garden, it continually threatens to creep stealthily across the carefully contrived boundaries of the social role or mask – the persona – that we show to the world.

For the Athenians the mythic image that expressed the irrational, the paradoxical and the mysterious was Dionysus, the god of the extremes of both ecstasy and madness. In his inebriated yet exalted state, he could bring joyous celebration as well as chaos and violence. He was paradox: the only god to suffer and die, and yet to always return. For a few centuries Greek myth and ritual struggled to hold the tension, the mystery and the tragedy of life that he represented. Classicist E. R. Dodds acknowledged that the rationalist elders of Athens “were deeply and imaginatively aware of the power, the wonder, and the peril of the Irrational.”

Ancient wisdom had told of the price that the psyche – and the community – paid for ignoring the mad god and his passions. Many of his myths told of the destructive vengeance he visited upon those mortals who denied the truth of reality – his reality. In story after story, Dionysus arrived from afar with his retinue of dancing maenads (related to mania) and drunken satyrs, only to be rejected by such

mythic figures as Lykourgos, Minyas, Proetus, Eleuther, Perseus, and most famously in Thebes by Pentheus (in The Bacchae by Euripides.)

mythic figures as Lykourgos, Minyas, Proetus, Eleuther, Perseus, and most famously in Thebes by Pentheus (in The Bacchae by Euripides.)

And time after time, Dionysus punished the unbelievers or their kin with madness. We are not talking about neurosis or depression. We are talking about madness so extreme, so severe that it caused them to unknowingly slaughter their own children.

Consider the three daughters of King Proetus of Tiryns. They refused to join Dionysus in his wild revels; in response he struck them mad. They infected the other women with their insanity, and all left their families. Some wandered as nymphomaniacs; others killed and ate their own children. One of the daughters died before the others were purified. Similarly, the women of Thebes who had rejected the God (including his own relatives) went violently mad.

The Athenians themselves told an old story: once in the dim past they did not receive the statue of Dionysus with appropriate respect when it was first brought to the city. Angered, the god sent an affliction on the genitals of the men. They were cured only when they duly honored him by fashioning great phalluses for use in his worship. After that education in proper respect the Athenian empire required its colonies to send phalluses (along with tribute) as part of the annual celebrations of the City Dionysia.

Scholars call these legends “myths of arrival,” implying that they explain the spread of a new cult. We, however, are looking for the archetypal implications. Why does the gentle and effeminate god of ecstasy arrive so often with such ferocity? Like alcohol itself, he loosens inhibitions. He was known as Lusios, the “Loosener.” James Hillman points out that the word is connected to lysis, the last half of the word analysis, which means “loosening, setting free, deliverance, dissolution, collapse, breaking bonds and laws, and the final unraveling as of a plot in tragedy.” A catalyst is an agent, chemical or otherwise, that precipitates a process or event, without being changed by the consequences.

What lies below the surface has great power because, like a diamond, it has been compressed by time. Like all of the “Others” of the world, the god has experienced the shame of having been cast out of the city, beyond the pale, among the barbarians, into the underworld, to lick his wounds and nurse his resentment. Are we really surprised that when he is invoked unconsciously, passively, or literally (by consuming spirits!) he is as likely to bring rage as he is to bring ecstasy? It would seem that when he comes back – and he always does, like ivy – the psyche experiences his arrival as the violent return of the repressed. But it need not always be this way. Psychologist Nor Hall comments on the daughters of Proteus:

Their bodies become covered with white splotches, and they are set out upon the hills to wander like cows in heat. Only now are they fitting partners for the God in bull form. Had they joined the Dionysian company willingly they would have enacted this state of wild abandon within a protective circle.

Indigenous ritual seeks to retrieve a state of balance that has been lost. To do so, it may involve – within such a protective circle – the symbolic enactment and emotional experience of our deepest conflicts and irreconcilable opposites, with the intention that such discord might not have to erupt – and disrupt – literally.

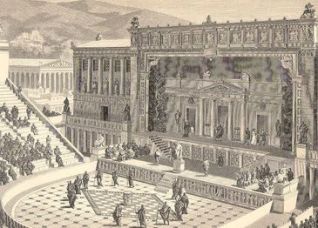

The Athenian religious and political leaders were faced with the question of how to pay attention to Dionysus – something they would rather not have done. How could they consciously invite this mad, unreasonable god of vengeance and wild emotional extremes – the “Other” – into the center of the city in the hope that he wouldn’t take vengeance? One way they accomplished this was in the Dionysia, the annual productions of tragic drama in March,where the entire city endured the tension of holding irreconcilable opposites together, as enacted onstage. These productions, by the way, were traditionally held in the Theater of Dionysus. The mad god was the patron saint, so to speak, of the Greeks' highest art.

Another method was to celebrate a late winter (the previous month, in early- to mid-February) festival called the Anthesteria – the festival of flowers – during which the new wine was opened. The city invoked Dionysus “as a purifier, not as a destroyer,” writes Charles Segal. The God arrived “bringing the life-enhancing benefits of viticulture and the drinking of wine.”

The Anthesteria was one of the earliest European all-souls’ festivals, in which the citizens annually welcomed the spirits of the dead, and along with them, Dionysus, back into the city for three days of drinking and merry-making. But, difficult as it may seem to modern consciousness, historians tell us that the joy alternated with deep somberness, even grief. Apparently, the people retained a memory of the ancient knowledge that it was impossible to invoke one extreme of experience without also accepting the presence of its opposite.

Dionysus, played by one of his priests, ceremonially returned from his annual sojourn in Persephone’s palace in Hades.

They towed him, wearing a bearded, two-faced mask, into the city on a ship on wheels that was crowned with vine tendrils and pulled by panthers. The citizens welcomed the god together with his wife Ariadne, the two of them returned from the sea, that universal symbol of the collective unconscious. We recall how Ariadne had helped save the hero Theseus from the Minotaur, the dreadful monster of the labyrinth; how Theseus had returned the favor by abandoning her on an island; and how Dionysus had saved her and married her. To celebrate their sacred marriage – the hieros gamos – Dionysus gave her a jeweled crown, which he later placed in the heavens as the constellation Corona Borealis.

Dionysus is also the source of the tradition of wearing masks in these processions. As Walter Otto wrote:

Because it is his nature to appear suddenly and with overwhelming might before mankind, the mask serves as his symbol and his incarnation in cult…(the mask) is linked with the eternal enigmas of duality and paradox.

The Greek word for mask was persona, and the mask reminded everyone of the untamed forces of nature that lay just below the surface of appearances. And yes, our modern words person and personality derive from that same source.

Similar festivals were held in mid-winter in Egypt and Rome. In Later centuries Christian Europe celebrated carnival during this same season, despite the disapproval of the church, and to this day masked revelers often tow the carnival King and Queen through the streets, just like Dionysus and Ariadne, on a ship on wheels.

Traditional European carnival was a time out of time, emphasizing both the liminal betwixt-and-between state as well as the cyclic nature of existence. It was a period of humor, paradox, wild behavior and a temporary inversion of the social order with a breaking of taboos that bordered on subversion. Anthropologist John Jervis writes that the people celebrated the body “… in all its messy materiality: eating, drinking, copulating, defecating, procreating, dying…” To an extent almost unimaginable today, entire communities participated – briefly – as equals, with little distinction between performers and audience, many of whom wore death masks. Amid the merriment, one can still observe the ancient theme of welcoming the spirits of the dead back to the world of the living for a few days.

But now, in the Christian context, the joy precedes the austerities of Lent, which is itself followed by more celebration. And the people invoke a different god of suffering and love – a spiritual god who is utterly disconnected from his dark, physical twin. And that twin remains in the underworld plotting his revenge. In the Protestant, Jewish and Moslem worlds, he is disconnected – unlike Dionysus – from his mother as well.