Part One

Show me a good loser, and I’ll show you a loser. – Vince Lombardi

April 2020, sheltering in place. Two dozen residents of a nursing home not five miles from here have been infected by the virus. I have a mask to wear outside – in New Orleans I’d say, “I’m masking” – but it’s raining, I’m stuck inside, can’t go for a walk, even with the mask. No ball games today in this weather. Yes, I’m warm, have food and family, have internet, have privilege. I have the privilege to comfortably whine about all the things that are wrong in the world today.

One of the things that is wrong, one of the important things that have been taken away is our seasonal ceremony of transition, Baseball’s Opening Day.

When I first posted this essay a few years ago it began like this:

The baseball season has begun, signaling to all Americans not born in Florida, California or the Southwest that the Divine Child of Spring has once again defeated Old Man Winter. The world (along with the home team’s pennant hopes, even if we know better) has been reborn once again. It’s no accident that Easter occurs at this time of year. Rebirth and redemption. New possibilities. It’s not over till it’s over, said Yogi Berra. Anything can actually happen, no matter what the score is. After all, baseball is the only major team sport that is not ruled by the clock. Let’s play two, said Ernie Banks.

Baseball, like all mythological narratives, lends itself to hyperbole and wild speculation. As Michael Meade has said, anything worth saying is worth exaggerating. And there is the mystery of baseball, to which we can consider three aspects. Hey, you’re stuck at home, too. Leave me in to pitch for a while. First, writes Randy Dankievitch,

Metaphorically speaking, the baseball is our soul, something we try to find…as we run away from home base (literally, home) and towards first, embarking on the adventure to find ourselves – with the ultimate goal of returning to the place it all began, to begin the journey anew the next time around the order.

Indeed, the only way to break out of the circle, any circle, is to return home – to successfully pass, as Robert Kelly writes, “the arcane and terrible passageway between Third and Home… past the Guardian of the Threshold”, the “birth canal”, and then, having scored, to enter it again, so to speak, next at bat, but at a higher level of being.

Second, uniquely among all team sports, we have that absence of any clock. Father Time – Chronos, the god who eats his children – has no power within the baselines. If the team at bat keeps hitting, the dream will not end, no matter the score, and its cyclical adventures continue, like myth, indefinitely.

Third, baseball is the only non-phallic sport. Bear with me here; I’m well aware of the shape of a bat. Think about it: all the other team sports – football, soccer, basketball, hockey, lacrosse and all of the sports with nets – all of them, even golf, involve my team pushing, throwing, kicking, batting (consider the military metaphor of shooting) or otherwise directing a ball, of no value in itself, into the sacred, protected territory of your team.

In scoring, we replicate the basic desire and intention of all our ancestors going back to micro-organisms, “a simple enactment on an easy symbolic plane,” writes Kelley, “of the biological commonplace, the old putting-it-in-the-hole…with their insertion of ball in slot they always celebrate, alas, enslavement of spirit to matter.”

Here is the intersection of sports, sex and warfare, as I write in The Singing Policeman:

On July 1st, 1916, as the British army rose from its trenches on the Somme River, some of their officers kicked soccer balls in front of the advance. It was one way to motivate those young men, 60,000 of whom would be mowed down before evening. Everyone on both sides of that ceremony of child sacrifice understood the metaphor; the British were attempting to penetrate (from a Latin root related to “innermost part of a temple”) the German lines. Perhaps the Yiddish verb shtup (“to overfeed, annoy, or to fuck”) is more appropriate. Everyone understood the patriarchal connection between sports, war – and sex.

So, since it clearly avoids the urge to shtup, I would go so far as to say that baseball, with its infield diamond, its non-symmetrical field, its disdain for time’s authoritarian demand for tidy endings, its rounding of the bases and its longing for home (nostos in ancient Greek, root of the word nostalgia, a longing for a place, not a time), has far more of the feminine in it than any sport.

I know, I know, in the grand scheme of things, count your blessings, yadda, yadda …but we have lost so many things that we innocently used to count on. So perhaps it’s even more appropriate to repost this now.

We have much to talk about. But first, return with me to those thrilling days of yesteryear, as the narrator to The Lone Ranger used to say, to a time when the oral tradition was still alive. Read the original version of Casey At the Bat, the full title of which is A Ballad of the Republic, Sung in the Year 1888, by Ernest Lawrence Thayer:

The outlook wasn’t brilliant for the Mudville nine that day;

The score stood four to two with but one inning more to play.

And then when Cooney died at first, and Barrows did the same,

A sickly silence fell upon of the patrons of the game.A straggling few got up to go in deep despair. The rest

Clung to that hope which springs eternal in the human breast.

They thought if only Casey could but get a whack at that –

We’d put even money now with Casey at the bat.But Flynn preceded Casey, as did also Jimmy Blake,

And the former was a lulu and the latter was a cake;

So upon that stricken multitude grim melancholy sat,

For there seemed but little chance of Casey’s getting to the bat.But Flynn let drive a single, to the wonderment of all,

And Blake, the much despised, tore the cover off the ball;

And when the dust had lifted, and the men saw what had occurred,

There was Jimmy safe at second, and Flynn a-hugging third.Then from 5,000 throats and more there rose a lusty yell;

It rumbled through the valley, it rattled in the dell;

It knocked upon the mountain and recoiled upon the flat,

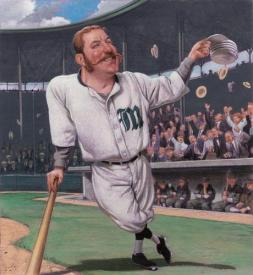

For Casey, mighty Casey, was advancing to the bat.There was ease in Casey’s manner as he stepped into his place;

There was pride in Casey’s bearing and a smile on Casey’s face.

And when, responding to the cheers, he lightly doffed his hat,

No stranger in the crowd could doubt ’twas Casey at the bat.Ten thousand eyes were on him as he rubbed his hands with dirt;

Five thousand tongues applauded when he wiped them on his shirt.

Then while the writhing pitcher ground the ball into his hip,

Defiance gleamed in Casey’s eye, a sneer curled Casey’s lip.And now the leather-covered sphere came hurtling through the air,

And Casey stood a-watching it in haughty grandeur there.

Close by the sturdy batsman the ball unheeded sped –

“That ain’t my style,” said Casey. “Strike one,” the umpire said.From the benches, black with people, there went up a muffled roar,

Like the beating of the storm-waves on the stern and distant shore.

“Kill him! Kill the umpire!” shouted someone on the stand;

And it’s likely they’d have killed him had not Casey raised his hand.With a smile of Christian charity great Casey’s visage shone;

He stilled the rising tumult, he bade the game go on;

He signaled to the pitcher, and once more the spheroid flew;

But Casey still ignored it, and the umpire said, “Strike Two.”“Fraud!” cried the maddened thousands, and the echo answered “fraud”;

But one scornful look from Casey and the audience was awed;

They saw his face grow stern and cold, they saw his muscles strain,

And they knew that Casey wouldn’t let that ball go by again.The sneer is gone from Casey’s lip, his teeth are clenched in hate;

He pounds with cruel violence his bat upon the plate.

And now the pitcher holds the ball, and now he lets it go,

And now the air is shattered by the force of Casey’s blow.Oh, somewhere in this favored land the sun is shining bright;

The band is playing somewhere, and somewhere hearts are light,

And somewhere men are laughing, and somewhere children shout;

But there is no joy in Mudville – mighty Casey has struck out.

Forget Uncle Walt, forget Emily, forget Frost and Eliot. This may not be great poetry, but for generations of Americans it has been a great poem.  Casey, wrote the poet Donald Hall in his remarkable essay in the centennial edition of the poem, is the most popular poem in our country’s history, if not exactly in its literature. It has spawned dozens of other poems over these 132 years, ranging from versions where Casey strikes out again to ones in which he redeems himself with a home run. See Casey’s Revenge (1907) or The Volunteer (1908), in which an aging Casey returns decades later to step out of the stands and save the day.

Casey, wrote the poet Donald Hall in his remarkable essay in the centennial edition of the poem, is the most popular poem in our country’s history, if not exactly in its literature. It has spawned dozens of other poems over these 132 years, ranging from versions where Casey strikes out again to ones in which he redeems himself with a home run. See Casey’s Revenge (1907) or The Volunteer (1908), in which an aging Casey returns decades later to step out of the stands and save the day.

Part Two

Outside of the limited range of our monotheistic tradition, all great mythic narratives have many versions. None of the retellings of Casey, however, have held our imaginations and hearts like a reading of the original poem. And for a very long time, we loved to listen to it. When the actor De Wolf Hopper first recited it onstage, The New York World reported,

The audience literally went wild…Men got up on their seats and cheered… it was one of the wildest scenes ever seen in a theatre.

Hopper literally made a career of this. From the 1890s to his death in 1935, he recited Casey onstage to enraptured audiences over 10,000 times. You can listen to his melodramatic rendition here.

For Donald Hall, the language of the poem

…is a small consistent comic triumph of irony. The diction is mock heroic, big words for small occasions: When a few fans go home in the ninth inning, they depart not in discouragement or disdain but “in deep despair.”

It may be comic opera, but it is still opera, and for all those generations of American fathers and sons, this is certainly not a small occasion. Casey “…crystallizes baseball’s moment, the medallion carved at the center of the game, where pitcher and batter confront each other.” By the way, another of Hall’s books is Fathers Playing Catch with Sons: Essays on Sport (Mostly Baseball).

And the critical factor is that we expect Casey to succeed, but instead he fails. Contrasts like this are the heart of both comedy and baseball. Each dramatic confrontation between batter and pitcher contains all the possibilities of great success or crashing failure. Even so, all but the very best hitters fail seven out of ten times. (Quick test: Whom do you picture yourself as, pitcher or batter, trying to score or trying to prevent a score, breaking boundaries or maintaining them?)

And the critical factor is that we expect Casey to succeed, but instead he fails. Contrasts like this are the heart of both comedy and baseball. Each dramatic confrontation between batter and pitcher contains all the possibilities of great success or crashing failure. Even so, all but the very best hitters fail seven out of ten times. (Quick test: Whom do you picture yourself as, pitcher or batter, trying to score or trying to prevent a score, breaking boundaries or maintaining them?)

We love this poem because it speaks about America, the land of opportunity, competition and achievement – the land of heroes. America is also about fair play and equal opportunity, the level playing field.

Competition vs equality. Wherever one of these values predominates, its shadow is nearby, and we are conflicted. In sports we’re talking about fairness vs. cheating. Fairness implies that all who play by the rules have a chance to prosper. Cheating, however, reveals capitalism’s core values and the realities of privilege. We love our fictional villains nearly as much as our heroes, precisely because they will do anything to win. Even in losing, they briefly unveil the shadow of our heroic ideals: competition actually trumps fairness, or at least until good triumphs over evil.

Why are so many outraged at drug use (or recently in baseball, sign-stealing) in sports? Our moral indignation expresses our innocent longing for ritual fields where everyone agrees on the rules, where the pursuit of money doesn’t overcome the purity of fairness, where men (and now women) free themselves for a while from the soul-killing pressure of office, store, factory, school, hospital, military preparedness, to race around the bases instead of with the rats, to be children again and just play.

Eldridge Cleaver, however, saw that when all secretly subscribe to the notion of “every man for himself”:

…the weak are seen as the natural and just prey of the strong. But since this dark principle violates our democratic ideals…we force it underground…spectator sports are geared to disguise, while affording expression to, the acting out in elaborate pageantry of the myth of the fittest in the process of surviving.

That process and its implication that only the fittest should survive is called “Social Darwinism” and it had arisen only a decade or so before Casey, although it is rooted deeply in American Puritanism. In our time, it has re-emerged in the conservative and religious drive to destroy all of the welfare state gains that progressives achieved in the 1930s and 1960s.

So Casey is perhaps the only enduringly popular American story in which the hero is a failure, or in current vernacular, a loser.  Now the death of the hero is hardly unique as a theme in literature. In dozens of stories heroes die saving the innocent community, defeating the evil Other (think of Sands of Iwo Jima, Saving Private Ryan, Titanic) just in the nick of time, or preventing the forces of evil from dishonoring the heroine.

Now the death of the hero is hardly unique as a theme in literature. In dozens of stories heroes die saving the innocent community, defeating the evil Other (think of Sands of Iwo Jima, Saving Private Ryan, Titanic) just in the nick of time, or preventing the forces of evil from dishonoring the heroine.

Consider also that, outside of the sacred containers of sport, the American hero’s opponent is not a pitcher but the racialized Other. Geronimo had surrendered only two years before Thayer wrote Casey. Northern Paiutes would begin the Ghost Dance a year later, followed shortly by the Wounded Knee massacre.  Ten years after Casey, the U.S. Army would begin to murder over 200,000 Filipinos. And regarding that other line – the color line – there is no consensus among historians. But one source declares that also in 1889, team owners agreed that no black men would be allowed to profane the sacred ground. They would enforce that decision until 1947.

Ten years after Casey, the U.S. Army would begin to murder over 200,000 Filipinos. And regarding that other line – the color line – there is no consensus among historians. But one source declares that also in 1889, team owners agreed that no black men would be allowed to profane the sacred ground. They would enforce that decision until 1947.

More commonly, of course, American heroes, though willing to die for the cause, live to ride off into the sunset. But when they do die, their defeats have meaning. They die for something, and in this way, they re-enact the essential American myth of regeneration through violence and the even more fundamental theme of Western culture itself, the willing sacrifice of the Son for his otherworldy Father. “Casey,” writes Hall,

…is Christlike: It is “With a smile of Christian charity” that he “stilled the rising tumult”; if we remember that this metaphoric storm occurs at sea (“the beating of the stormwaves”), we may understand that Casey’s charity earns its adjective.

Casey, however, just plain strikes out. Game over. There is no willing sacrifice, no meaning, nothing learned, unless we take the Puritan perspective that Casey had been guilty of the sin of pride. But mostly, the remaining fans slink home, their adrenalin rush dissipated, hungry for dinner. Game over. As foot soldiers often said in Viet Nam, It don’t mean nothin’.

Of course, Casey, despite his “smile of Christian charity”, does arrogantly let the first two pitches go by before striking out (we never learn if he even attempts to swing at the third one). Some might condemn him for not behaving in the approvingly restrained, modest, Puritan manner…nahhh. Casey is a hero, and heroes are privileged to choose and re-choose their styles, as Trumpus proves on a daily basis (I use this term to remind us all that this President is embodying and enacting our mythic narratives. We are all Trumpus).

American heroes, very much like the villains they oppose in westerns, crime dramas (think Dirty Harry), spy thrillers (think James Bond) and science fiction, are privileged to ignore the conventions of fair play and silly legalisms when they need to defeat the Other. Think Oliver North. Think Richard Nixon (“When the President does it, that means that it is not illegal”).

But Casey is the hero who loses. And here is the essence of our fascination with him. We aspire to be heroes and winners, but we identify with the losers. I have written extensively about Hero mythology in America, and I encourage interested readers to read Chapter Nine of my book Madness at the Gates of the City: The Myth of American Innocence or my essay, “The Hero Must Die.”

Part Three

In the context of this discussion of Casey, here are three themes to ponder:

1 – Unlike most other traditions, our monotheistic legacy has culminated in American narratives that offer only two fundamental mythic images: the hero and the villain. These two in turn give us sub-categories such as winners and losers, or predators and victims. This zero-sum, winner-takes all world gives our inner fantasy worlds very little room for nuance. It is a profoundly diminished condition of the soul and it has ramifications in every aspect of life, from our health to our relationships to our economics to our politics. Casey and the unnamed pitcher begin as hero and villain, but he ends as loser or victim. In another mythic universe, Casey would not have been so arrogant as to ignore those first two pitches. (Or this: the Hall of Fame pitcher Robin Roberts claimed that his greatest thrill in baseball was seeing Micky Mantle come to bat with the wind blowing out in the 1953 All-Star game and bunting).

2 – Our radical obsession with individualism demands personal accountability, except of course for large corporations. For the rest of us the message is clear: if a man succeeds he does so not because of communal support networks or family inheritance, but alone, having “pulled himself up by his own bootstraps” (a phrase that first appears in print in 1834, nine years before “manifest destiny” does). This belief, American to its core, is both mythological and theological. “This is America,” said Jerry Falwell, our best-known televangelist a hundred years after Casey, “…If you’re not a winner it’s your own fault.”

This is crazy-making. On the surface, Americans, until very recently, have always held hugely unrealistic expectations of themselves compared to Europeans. This (along with our racist bellicosity) is what makes us Americans. As John Steinbeck said, “Socialism never took root in America because the poor see themselves not as an exploited proletariat but as temporarily embarrassed millionaires.”

But under the surface, we are all, as James Hillman said, psychologically Christian. We are not simply Protestants in character but Puritans. We’re losers – or self-proclaimed sinners – and many studies have shown that when we perceive ourselves as falling backwards in the rat race – or when we lose the blue-collar jobs that once provided us with middle-class lifestyles – we really do believe that it’s our own fault. Crazy-making. For a deeper dive into this issue, see my series “A Vacation in Chaos”.

3 – But perhaps the most profound thing that characterizes us as Americans is our refusal to look at our own darkness. How much easier it is to project our self-contempt upon convenient scapegoats. This is the root of that racist bellicosity that, for much of the world’s people, cancels out our invitation to prosper in the primary colors of capitalist progress. But Casey doesn’t even have that luxury; he simply fails.

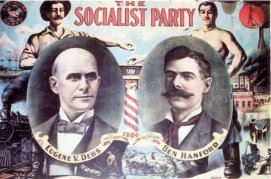

A Ballad of the Republic, Sung in the Year 1888: It is significant that Ernest L. Thayer wrote Casey at this time and that it soon became massively popular. The ancient jihad against the external Red Other (the Native Americans) had only recently been displaced onto a new Red Other – communism. There were literally thousands of incidents of strikes, dozens of anarchist bombings and countless incidents of vicious police repression in these years. The Haymarket riots (which led to International Worker’s Day on May first) had happened only two years before.

Why was there so much agitation? Because it was the height of the “Gilded Age,” when the “Robber Barons” and other industrialists were accumulating unprecedented, massive fortunes and millions of (white) Americans were sinking down for the first time – despite the prevailing Horatio Alger myth of rising up by one’s own bootstraps – into severe poverty. Reconstruction had ended twelve years before. The South was well on its way to reversing most gains that African Americans had made since the Civil War and instituting a rigid system of Jim Crow segregation. And for white American males, to fall back or sink down economically was to risk having the boundary line between them and the Black Other erased. For some, this meant to unite with blacks and fight the oligarchs together; but for most whites it meant supporting any bigot politician who promised to re-instate that boundary line, just as the baseball owners were doing.

Does this sound similar to our own time? The massive extremes of wealth and poverty certainly should. The workers did, however, counter the ideology of “blame yourself” with the socialist and anarchist philosophies of “we can do this together.” Many of them were recent immigrants from Europe (which lacked both our heritage of extreme individualism and our Puritan tradition of blaming the victims), and they threatened the power structure as in no other period in American history.

Perhaps this is why the gatekeepers of racial purity went to such great lengths to shift blame for the economy and its periodic financial crashes onto the familiar internal Other (blacks) and the new external Other (reds). There were at least 5,000 lynchings between 1890 and 1930. The vast majority of the victims were black men. But not all: in 1891 a New Orleans mob murdered eleven Italian Americans, two years before the financial panic of 1893.

For the first time, most white Americans were finally acknowledging that they too were losers in this game. But the communal thinking that might have offered real alternatives was forced underground by massive repression. Still, Populists, Progressives and Socialists would persist in agitating for real change.  Eugene Debs, imprisoned for his opposition to U.S. involvement in World War One, campaigning from jail, received nearly a million votes for president in 1920. But it would be nearly a century before an American politician would sense that the winds might be changing and proudly (if tepidly) describe himself as a socialist.

Eugene Debs, imprisoned for his opposition to U.S. involvement in World War One, campaigning from jail, received nearly a million votes for president in 1920. But it would be nearly a century before an American politician would sense that the winds might be changing and proudly (if tepidly) describe himself as a socialist.

Winners and losers. Throughout these hundred years, the elites have counted on the fact that millions will identify with those fascists who could most easily manipulate their emotions, from the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s to Father Coughlin in the thirties, to Joe McCarthy in the fifties, to Ronald Reagan and Trumpus, whose most virulent insult is “loser.”

Yes, most of us, most of the time, are losers, but it sure feels good when he describes someone else as one. How sweet to have that burden lifted and dropped onto someone else. And how it pulls us out of our depressed (in more than one sense) state to identify with a self-described “winner.” How sweet to hear him describe the corona virus as the “Chinese virus”. But the exhilaration, like that of any addiction fades.

So Casey loses, and we lament his failure (unless we were pitchers when we were young, but then only the best players were pitchers or shortstops), because we know what it’s like to fail. Or perhaps we appreciate the sweet irony of his downfall – there’s that arrogance, after all – it’s a guilty pleasure to see the high and mighty brought down to earth. It’s the pleasure that lives in the shadows of our cult of celebrity.

This is a fourth characteristic of American myth in what Joseph Campbell described as our demythologized world. Prior to the ascendance of monotheism, tribal and pagan cultures had always provided multiple images of the great archetypal forces that move through psyche and culture. For over 150 years, however, we have lived with the “toxic mimic” of that imaginal world – the cult of celebrity, as embodied  primarily not even by people but by images of people on screens and pages.

primarily not even by people but by images of people on screens and pages.

But archetypes are images of perfection, and no celebrity, be it Elvis, Marilyn, Casey or Trumpus can hold the projections and hopes of millions without eventually revealing their all-too-humanness. Then, woe to them, because as much as we love them, isn’t it one of the guiltiest of pleasures to see them fall from grace! Hall notes that

…hero-worship is dangerous and needs correction, especially in a democracy if we will remain democratic. To survive hero-worship we mock our heroes; if we don’t, we become their victims.

It can – and should – be profoundly disturbing to discover that we have projected our deepest selves – our inner royalty – upon celebrities, only to inevitably discover that they are quite imperfectly human. Better to rejoice at their catastrophes (“to move downward”) than to ponder our own willingness to give ourselves away, and to turn our gaze toward some other image that may carry our dreams for a while. To read more about both the Gilded Age and the cult of celebrity, read my essay “We Like to Watch: Being There with Trump.”

So our response to Casey’s failure is complicated indeed, and always will be. Or at least as long as we know what it is to lose when mass culture is constantly encouraging us to improve, to progress, to move up the food chain, to make something of ourselves, to “be all you can be,” or even to “Do What You Love, The Money Will Follow”.

In America, to acknowledge one’s expendable condition under capitalism is to open up the floodgates of repressed anger. For some, this can lead to rejecting the philosophy of every man for himself and joining the common struggle. But for others the temptation to let that anger out onto scapegoats provided by the media is overwhelming. And for a small but influential minority, that anger regularly turns into extreme violence.

But it is also true that becoming familiar with the shadow side of our mythology can also feel surprisingly comforting. How the pressure dissolves – to win, to succeed, to produce, to be number one, to be exceptional, to maintain phallic dominance, to rise in status, to keep up with the Jones’, to be a man, to police and save a world that has never appreciated our smile of Christian charity.

Donald Hall, before he died, gifted us with an alternative (not a re-write) to Casey:

Old Timer’s Day

When the tall puffy

figure wearing number

nine starts

late for the fly ball,

laboring forward

like a lame truck horse

startled by a garter snake,

this old fellow

whose body we remember

as sleek and nervous

as a filly’s,

and barely catches it

in his glove’s

tip, we rise

and applaud weeping:

On a green field

we observe the ruin

of even the bravest

body, as Odysseus

wept to glimpse

among shades the shadow

of Achilles.

(Talking about heroes, who is the tall, puffy figure? Hint: He wears # 9 and Hall lived in New England. Read John Updike’s classic essay, “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu”.

For more great literary writing on baseball, the anthology Baseball I Gave You the Best Years of My Life includes Robert Kelly’s “A Pastoral Dialogue on the Game of the Quadrature,” from which I glean some of the more mystical material in this essay.

Finally, some thoughts about losing from the American mystic and poet Adyashanti:

Enlightenment is a Gamble

Time to cash in your chips, put your ideas and beliefs on the table.

See who has the bigger hand, you or the Mystery that pervades you.

Time to scrape the mind’s shit off your shoes

Undo the laces that hold your prison together

And dangle your toes into emptiness.

Once you’ve put everything on the table once all of your currency is gone

And your pockets are full of air

All you’ve got left to gamble with is yourself.

Go ahead, climb up onto the velvet top of the highest stakes table.

Place yourself as the bet.

Look God in the eyes

And finally, for once in your life, lose.