The Industrial Revolution in the United States required millions of new workers, yet immigration policy was highly selective. For over a century, the Supreme Court periodically determined who was Other (see Part Three below). Admission to whiteness was an invitation to emerge from darkness and walk in innocence. In a thousand small but consistent ways, law and custom defined white persons in terms of what they weren’t. The “boundaries of whiteness,” writes historian Judy Helfand, “were constructed by exclusion.”

The 1838 Trail of Tears tells us much about how we define otherness. The Cherokees, known with others as the “civilized tribes,” were prosperous, literate, Christian farmers who lived in towns and passed all the cultural tests of whiteness, even publishing their own newspapers. But politics, economics and hatred determined Andrew Jackson’s motives. Unable to dispossess Indians for not utilizing the land (the previous standard of whiteness), he could still argue that they were biologically inferior. Thousands died – Indians, not “white pioneers” – during the westward trek. Later, few white Americans saw any irony when Jackson referred to the annexation of slaveholding Texas as “expanding the area of freedom.”

Ethnic cleansing. Take note, please, that 150 years later, exactly the same process, with the same hideous results, occurred when the Israeli army expelled 50-70,000 Palestinians from their ancient city of Lydda and pushed them out into the desert.

Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of Catholic Germans and Irish were arriving. By 1860 one in seven Caucasians was foreign-born, and the struggle to define “us” accelerated. The Irish were forced to compete with free blacks for the lowest-paying urban jobs, but received some degree of privilege based on their color.

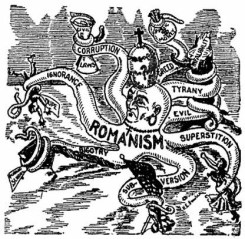

Catholics were another special case. Although Caucasian, they were looked upon with great suspicion by “native,” Northern European Protestants. Predictably, Irish-black tensions erupted into the New York draft riots of 1863, in which hundreds perished. Richard Hofstadter, in his classic book The Paranoid Style in American Politics, writes:

Anti-Catholicism has always been the pornography of the Puritan…the anti-Catholics developed an immense lore about libertine priests, the confessional as an opportunity for seduction, licentious convents and monasteries, and the like. Probably the most widely read contemporary book in the United States before Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a work supposedly written by one Maria Monk, entitIed Awful Disclosures, which appeared in 1836. The author, who purported to have escaped from the Hotel Dieu nunnery in Montreal after a residence of five years as novice and nun, reported her convent life there in elaborate and circumstantial detail…Infants born of convent liaisons were baptized and then killed, she said, so that they might ascend at once to heaven. A high point in the Awful Disclosures was Maria Monk’s eyewitness account of the strangling of two babies.

Anti-Catholicism, like anti-Masonry, mixed its fortunes with American party politics…it did become an enduring factor in American politics…the depression of 1893, for example, was alleged to be an intentional creation of the Catholics, who began it by starting a run on the banks. Some spokesmen of the movement circulated a bogus encyclical attributed to Leo XIII instructing American Catholics on a certain date in 1893 to exterminate alI heretics, and a great many anti-Catholics daily expected a nation-wide uprising. The myth of an impending Catholic war of mutilation and extermination of heretics persisted into the twentieth century.

Here is the perverse genius of the story of American immigration, the conversion of natural class-consciousness into racialized identity. As more “foreigners” arrived from southern and eastern Europe, nativist reactionaries forced each group to temporarily carry the mantel of the Other. Most first generation Italian, Polish, Irish, Slavic, Greek and Jewish immigrants were identified as being somewhat less-than-white, or conditionallywhite. In addition, because they were “urban” (a phrase that later became a euphemism for “black”), American myth assigned them lower status in the hierarchy compared to the WASPs further inland.

Many Southern Italian and Sicilian immigrants immigrated to Jim Crow New Orleans, where their darker skin provoked anxiety among whites, who could not determine if they were white or black. Predictably, economic pressures led to local whites treating them with scorn. In 1891 a mob lynched a group of eleven Italian-Americans.

By that time, labor strife had replaced the Indian wars in the national imagination, and immigration took on new political implications. Sam Smith writes:

This was the period of the great post-reconstruction counter revolution during which corporations gained enormous power but the rest of America and its citizens lost it….The counter-revolution was not only an attack on would-be immigrants, it was aimed at American ethnic groups who had proved far too successful at adding to their political clout in places like Boston and New York City…In truth, what really scares the exclusionists is the politics of immigrants, potentially more progressive than they would like…In the end, we don’t really have an immigration policy but an exclusion policy, outsourcing our prejudices by not letting their targets enter the country.

I would add to this analysis that we have plenty of examples in which non-whites were allowed into the country – or into the job market – specifically because their presence was either of great value to the business community or because it would deflect the natural political anger of white workers.

Americans of all colors and classes, of course, have engaged in internal migrations since the beginning, from the expansion of the frontier to the northward movement of blacks after World War One, the “Oakies” who left the Dust Bowl for California in the 1930s, the “Hillbilly” migration from Appalachia to the Midwest after World War Two and the emptying out of the “Rust Belt” in the 1980s. Ironically, this last internal migration reversed a northward movement that the great-grandparents of these same white workers had made.

How free were African-Americans to move around, even for short periods? Sundown towns were all-white municipalities or neighborhoods that enforced restrictions excluding non-whites via some combination of discriminatory local laws, intimidation, and violence.

Essentially any Blacks or Native Americans who were found in sundown towns after sunset were subject to harassment, threats, and violent acts—up to and including lynching. Jews were also excluded from living in some of these towns, such as Darien, Connecticut and Lake Forest, Illinois (which kept anti-Jewish and anti-African-American housing covenants until 1990). There were at least 10,000 sundown towns in the United States as late as the 1960s. They were not limited to the South—they ranged from Levittown, New York, to Glendale, California, and included the majority of municipalities in Illinois.

Between 1890 and 1920, eleven million rural people migrated from all over the country to the cities of the North and the Midwest. This migration, combined with the influx of twenty million “foreigners,” resulted in new fears that the spiritual and physical Apollonian essence of “native” America would be cheapened by such groups who, in comparison, seemed to display much more Dionysian characteristics.

Nativists responded by cranking up the machinery of propaganda once again. As always, America’s gatekeepers helped frame the debate. Scientists and intellectuals (including Leland Stanford, president of Stanford University) argued that moral character was inherited, that “inferior” southern and eastern Europeans polluted Anglo-Saxon racial purity. Woodrow Wilson, President of Princeton and future leader of the nation, contrasted “the men of the sturdy stocks of the north” with “the more sordid and hopeless elements” of southern Europe, who had “neither skill nor quick intelligence.”

As a result, 27 states passed eugenics laws to sterilize “undesirables.” A 1911 Carnegie Foundation “Report on the Best Practical Means for Cutting Off the Defective Germ-Plasm in the Human Population” recommended euthanasia of the mentally retarded through the use of gas chambers.

Gas chambers.

The proposed solution was deemed too controversial. But in 1927 the Supreme Court, in a ruling written by Oliver Wendell Holmes, allowed coercive sterilization to proceed. Ultimately, 60,000 American citizens suffered this fate. Congress did not strike down the last of these laws until the 1970s. Meanwhile, in Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler praised American eugenic ideology, and in the 1930s, Germany copied American racial and sterilization laws. Years later, at the Nuremberg trials, the Nazis quoted Holmes’s words in their own defense.

But the myth of a nation uniquely devoted to freedom and equality had unprecedented and undeletable potency. The melting pot (a phrase already in use by the 1780s) was a metaphor for the idealized process of immigration by which different nationalities, cultures and races were to blend into a new, virtuous community, and it was connected to utopian visions of the emergence of an American “new man.” In 1908 Israel Zangwill’s play The Melting Pot instructed recent immigrants that the route to happiness was through whiteness, individualism, “pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps” and distancing oneself from ethnicity. In the play, the immigrant protagonist declared:

Understand that America is God’s Crucible, the great Melting Pot where all the races of Europe are melting and re-forming! Here you stand, good folk, think I, when I see them at Ellis Island, here you stand in your fifty groups, your fifty languages, and histories, and your fifty blood hatreds and rivalries. But you won’t be long like that, brothers, for these are the fires of God you’ve come to – these are fires of God. A fig for your feuds and vendettas! Germans and Frenchmen, Irishmen and Englishmen, Jews and Russians—into the Crucible with you all! God is making the American.

Granted, the speaker is European, but we should take note that his rousing speech doesn’t include non-Caucasians.

Like Zangwill, “Old stock” Americans equated the melting pot with the total assimilation of European immigrants. In 1914 Henry Ford established a school for his workers. Its graduation ceremony involved symbolically stepping off an immigrant ship and passing through the melting pot, entering at one end in costumes designating their nationality and emerging at the other end in identical suits and waving American flags. They were no longer the outer Other.

America’s internal Other, however, remained deeply mired in institutional racism. In 1906 Theodore Roosevelt declared in his State of the Union Message, “The greatest existing cause of lynching is the perpetration, especially by black men, of the hideous crime of rape – the most abominable in all the category of crimes, even worse than murder.”

Why did his audience understand that rape by a black man was worse than murder? Since white women were saddled with a role in the narrative of white supremacy – the essence of purity – rape was pollution by the bodily fluids of the Other; it was penetration through the veil of innocence.

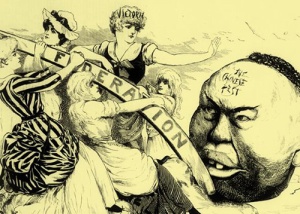

Here was a situation absolutely unique in the history of world migrations. Each immigrant group quickly vaulted past blacks and Latinos in the social hierarchy. As they assimilated, media and politicians projected Dionysian qualities onto newer immigrants. Interracial worker solidarity was nullified by the constant threat of blacks and Latinos coveting the jobs – and, they were told, the daughters – of white workers. The pattern set in 1680 Virginia (see Chapter Seven of my book) held everywhere. When Wilson became President he instituted racial job segregation at the federal level. In a society equally constructed on dreams of progress (“getting ahead”) and nightmares of race (“miscegenation”), no one could afford to fall backwards. Recent immigrants who had been accepted as white feared contamination by non-whites. In America, “under-class” meant “underworld.”

In a society constructed on dreams of progress (“getting ahead”) and nightmares of race (“miscegenation”), no one could afford to fall backwards. Recent immigrants who had been accepted as white feared contamination by non-whites. In America, “under-class” meant “underworld.”

In the west, since Chinese, blacks and Indians weren’t allowed to testify against whites, hundreds of murders went unprosecuted. Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act and amended it regularly until it was repealed in 1943. Filipino immigration was limited to fifty persons per year until 1965. Until 1931, “native” white women who married Chinese men lost their citizenship. Some argue that whites hated the Chinese because, like Orthodox Jews, many Chinese stubbornly retained their cultural identity, thus insisting on their otherness. This example illuminates one of the rules of othering: only whites may determine who the Other is.

Another rule: when white privilege and identity are questioned, enormous rage can erupt, especially when the economic depressions, or panics, occurred, as they did in 1796, 1815, 1837, 1857, 1873, 1890, 1901, 1907, 1920, 1929 and 2008. Historians have connected increased anti-immigrant violence with most of these dates.

These people are stock characters in our story of the melting pot that took people of diverse backgrounds and made Americans of them. However, as Chomsky has pointed out, the “Ellis Island” narrative is a white narrative (see below for the contrasting story of Angel Island). By 1917, with expansions of the Chinese Exclusion Act, fully three-quarters of the world’s population was ineligible to become American, based purely on their racial identity.